Није.

И не каже се ирудуцибилно већ иредуцибилно, од латинског

reduco.

Не значи. То значи да није могуће да постоји такав део с истом или другачијом функцијом мање комплексности, а постоји.

И о овоме смо већ говорили на теми, али, као и увек...

Није.

И не каже се ирудуцибилно већ иредуцибилно, од латинског reduco.

a jel, da vidimo sta kaze naucnik sto ih je studirao mnogo godina:

evo ti direktno sta kazu laboratorijske analize Bakterijskog motora, da li moze biti ireducibilno komplexna stvar.

How do evolutionists explain away such exquisite design?

Scientific American tried to explain this amazing miniature motor by evolution, by claiming that the parts were ‘co-opted’ from other functions:

‘The sophisticated components of this flagellum all have precedents elsewhere in nature …

‘In fact, the entire flagellum assembly is extremely similar to an organelle that Yersinia pestis, the bubonic plague bacterium, uses to inject toxins into cells. …

‘The key is that the flagellum’s component structures … can serve multiple functions that would have helped favor their evolution.’1

Scientific American’s argument is like claiming that if the components of an electric motor already exist in an electrical shop, they could assemble by themselves into a working motor. However, the right organization is just as important as the right components.

Dr Scott Minnich of the University of Idaho, a world expert on the flagellar motor, disagrees with Scientific American. He says that his belief that this motor has been intelligently designed has given him many research insights. Minnich points out that the very process of assembly in the right sequence requires other regulatory machines.2 He also points out that only about 10 of the 40 components can possibly be explained by co-option, but the other 30 are brand new.

Finally, Dr Minnich’s research shows that the flagellum won’t form above 37°C; instead, some secretory organelles form from the same set of genes. But this secretory apparatus, as well as the plague bacterium’s drilling apparatus, are a degeneration from the flagellum. Minnich says that although it is more complex, the motor came first, so it couldn’t have been derived from them.3

References

- Rennie, J., 15 Answers to Creationist Nonsense, Scientific American287(1):78–85, July 2002; refutation after Sarfati, J., Refuting Evolution 2, pp. 167–170, Master Books, Arkansas, USA; Answers in Genesis, Brisbane, Australia, 2002.

- Unlocking the Mystery of Life, DVD, Illustra Media, 2002.

- See Minnich, S www.idurc.org/yale-minnich.html, 25 August 2003.

Ko je Scott Minnich?

Scott Minnich holds a Ph.D. from Iowa State University and is currently a professor of microbiology at the University of Idaho

Spinning Tales About the Bacterial Flagellum

https://evolutionnews.org/2010/01/spinning_tales_about_the_bacte/

Ken Miller has been making the same objections about irreducible complexity and the bacterial flagellum for a long time. In his Dover testimony, his book

Only a Theory, and in other writings he argues that irreducible complexity for the flagellum is refuted because about 10 flagellar proteins can also be used to construct a toxin-injection machine (called the Type-III Secretory System, or T3SS) that some predatory bacteria use to kill other cells. Miller may even boast that Judge Jones ruled that the T3SS explained how the bacterial flagellum could evolve: “[W]ith regard to the bacterial flagellum, Dr. Miller pointed to peer-reviewed studies that identified a possible precursor to the bacterial flagellum, a subsystem that was fully functional, namely the Type-III Secretory System.”

33

However, there are strong reasons to doubt these hypotheses.

First, leading biologists argue that phylogenetic data implies the T3SS could not have been a precursor to the flagellum.

34 As

New Scientist reported:

One fact in favour of the flagellum-first view is that bacteria would have needed propulsion before they needed T3SSs, which are used to attack cells that evolved later than bacteria. Also, flagella are found in a more diverse range of bacterial species than T3SSs. “The most parsimonious explanation is that the T3SS arose later,” says biochemist Howard Ochman at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

35

Second, the T3SS is composed of only about ¼ of the proteins in the flagellum, and does not help one account for how the fundamental function of the flagellum–its propulsion system–evolved. The unresolved challenge that the irreducible complexity of the flagellum continues to pose for Darwinian evolution is starkly summarized by William Dembski: “At best the T[3]SS represents one possible step in the indirect Darwinian evolution of the bacterial flagellum. But that still wouldn’t constitute a solution to the evolution of the bacterial flagellum. What’s needed is a complete evolutionary path and not merely a possible oasis along the way. To claim otherwise is like saying we can travel by foot from Los Angeles to Tokyo because we’ve discovered the Hawaiian Islands. Evolutionary biology needs to do better than that.”

36

Dembski’s critique is apt because it recognizes that Miller wrongly characterizes irreducible complexity as focusing on the non-functionality of sub-parts. In contrast, Behe properly tests irreducible complexity by assessing the plausibility of the entire functional system to assemble in a step-wise fashion, even if sub-parts can have functions outside of the final system. The “leap” required by going from one functional sub-part to the entire functional system is indicative of the degree of irreducible complexity in a system. Contrary to Miller’s assertions, Behe never argued that irreducible complexity mandates that sub-parts can have no function outside of the final system.

Miller misconstrued the proper way of testing irreducible complexity, and his argument amounts to this:

if my laptop’s power cord could also be used to power my toaster, then my laptop is no longer irreducibly complex. Because a laptop requires a number of parts necessary for function, this is preposterous. So is Dr. Miller’s straw method of testing irreducible complexity, as illustrated in the following 2 diagrams:

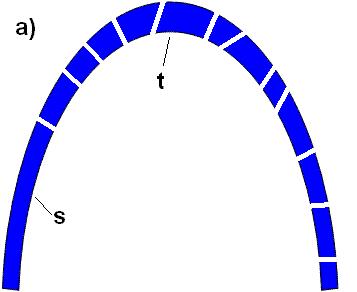

Figure A: Consider an irreducibly complex functional arch, divided up into many pieces, including s and t:

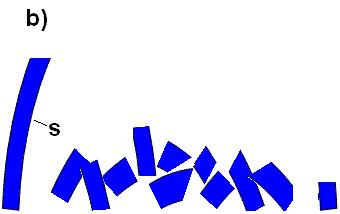

Figure B: Take away the keystone of the arch, t, and the arch falls down. But piece s may be left standing:

Does the fact that part of the arch, s, remains standing imply that the rest of the arch is not irreducibly complex? Of course not. In the same way, the fact that a fraction of the flagellum helps form a T3SS does not imply that the flagellum itself is not irreducibly complex. To refute irreducible complexity, Dr. Miller would have to show how a fully functional flagellum could form in a step-by-step fashion. He hasn’t shown anything close to that. |

In contrast, pro-ID microbiologist Scott Minnich has properly tested for irreducible complexity through genetic knock-out experiments he performed in his own laboratory at the University of Idaho. He presented this evidence during the Dover trial, which showed that the bacterial flagellum is irreducibly complex with respect to its complement of thirty-five genes. As Minnich testified: “One mutation, one part knock out, it can’t swim. Put that single gene back in we restore motility. Same thing over here. We put, knock out one part, put a good copy of the gene back in, and they can swim. By definition the system is irreducibly complex. We’ve done that with all 35 components of the flagellum, and we get the same effect.”37

Moreover, Scott Minnich explained that even if Miller’s speculative scenario turned out to be true, it would not be sufficient to prove a Darwinian explanation for the origin of the flagellum because there is still a huge leap in complexity from a T3SS to a flagellum. Unfortunately, Judge Jones ignored Scott Minnich’s research and testimony supporting irreducible complexity of the flagellum, and instead ruled that Miller refuted the irreducible complexity of the flagellum. Ironically, a review article in Nature Reviews Microbiology the following year admitted that “the flagellar research community has scarcely begun to consider how these systems have evolved.”38 Did Miller actually demonstrate the flagellum could have evolved by Darwinian evolution?