Khal Drogo

Elita

- Poruka

- 18.161

Тема о Францима на овом птф не постоји. Како је у питању народ који не што је у једном времену имао пресудну улогу у европској историји него бјеше и супстрат у етногенези данашњих Француза и Њемаца, народа који ће обликовати и каснију историју и данашњу Европу каква јесте. Па да отворим тему о овом итекако важном народу.

Намјера ми је да се кроз тему сагледамо тај период европске историје и улогу Франала, период самог краја времена Антике и рани средњи вијек, од првог иоле значајног франачког владара Хлодиа половином V вијека, временом династија Меровинга и Каролинга, па до X вијека, када ће се након Верденског споразума 843.године Франачка подијелити на три царства од којих ће свако имати засебан ход кроз европску историју.

Временом су наметнули власт над многим другим пост-римским краљевствима и германским народима. Нешто касније, католичка црква је признала франачке владаре као насљеднике старих владара Западног римског царства.

Франци (енгл.википедија овдје) су народ састављен од неколико германских племена. Уједно и прво германско племе које се стално настањује на подручју Римског царства.

Њихово име се први пут помиње у римским изворима из III вијека. Дошли су на подручје Римског царства из садашње средишње Немачке и јужне Холандије и населили су северну Галију, где су прихваћени од Римљана као федерати.

Ту успостављају државу Франачку, која покрива већину данашње Француске, Белгије, Холандије и западних подручја Њемачке. Тиме су Франци створили историјско језгро из којег ће касније настати модерна Француска, Њемачка, Белгија и Холандија.

По предању краљ Клодвиг (Хлодовех или Кловис како га још помињу) 496.године прелази на ортодоксно хришћанство (ортодоксно у смислу да је вјерно закључцима на никејском сабору 325.године, насупрот аријанства које су тада већ прихватили доминантни германски народи Вандали и Готи), један од најважнијих догађаја у историји Европе раног средњег вијека и који ће одредити будуће процесе а и у доброј мјери обликовати оно што би касније могли назвати западноевропском цивилизацијом.

Послије краља Клодвига, како су Франци дијелили краљевство на све синове, Франачка је под Меровинзима била изложена цијепању и династичким борбама, и то бјеше једно краљевство са доста подкраљевстава, огранака династије Меровинга.

Династија Меровинга је франачким краљевством владала “де јуре“ до 751.године и Хилдерика III.

Но “де факто“ задњи меровиншки краљ који је имао моћ и истински владао бјеше Дагоберт I који је вадао 629-639.године и који је љуте битке водио са моћним словенским краљем Самом. Након њега, стварна моћ је прешла у руке мајордома (начелник двора), краљевске дужности су сведене на церемонијалне и протоколарне, ови Меровинзи након Дагоберта би понекад били названи и краљеви љенштине, а о свим пословима у краљевству бригу је водио и одлуке доносио мајордом.

Посебно моћан мајордом бјеше у другој половини VII и на прелазу VIII вијек Пипин Хересталски, којег је наслиједио његов ванбрачни син (ако је био уопште син) Карло Мартел, још способнији и одважнији, којег насљеђује Пипин III, који ће у договору са папом којем је за узврат поклонио читаву државу (Папинску државу) и још бројне уступке, довршио еру Мероинга, крунисао се краљем 751.године када почиње ера Каролинга.

Још моћнији од Пипина III бјеше његов син, Карло Велики, који шири франачко краљевство, да би га на Божић 25. децембра 800.године папа крунисао за цара Светог римског царства. Та церемонија је Карлу Великом формално признала насљедство над Западним римским царством, Византија се са тиме разумљиво није слагала јер су папе политички ауторитет да то раде заснивале на фалсификованом документу, но хришћански свијет и Европу су ушли у нову еру. Сам Карло Велики је ипак себе чешће звао краљем Франака и Лангобарда.

Карлов насљедник Лудвиг бјеше побожан али не и капацитет оца, дијелове Франачког царства даје на управу својим синовима, а најстаријег сина Лотара I проглашава 823.годне сувладаром. Остала двојица сунова незадовољни започињу рат, који се окончава 843.године Верденским споразумом, којим је Франачка подијељена на три дијела.

О свему овоме, написаће се још која на теми.

Намјера ми је да се кроз тему сагледамо тај период европске историје и улогу Франала, период самог краја времена Антике и рани средњи вијек, од првог иоле значајног франачког владара Хлодиа половином V вијека, временом династија Меровинга и Каролинга, па до X вијека, када ће се након Верденског споразума 843.године Франачка подијелити на три царства од којих ће свако имати засебан ход кроз европску историју.

Временом су наметнули власт над многим другим пост-римским краљевствима и германским народима. Нешто касније, католичка црква је признала франачке владаре као насљеднике старих владара Западног римског царства.

Франци (енгл.википедија овдје) су народ састављен од неколико германских племена. Уједно и прво германско племе које се стално настањује на подручју Римског царства.

Franks

The Franks (Latin: Franci or gens Francorum) were a group of Germanic peoples[1] whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.[2] Later the term was associated with Romanized Germanic dynasties within the collapsing Western Roman Empire, who eventually commanded the whole region between the rivers Loire and Rhine. They imposed power over many other post-Roman kingdoms and Germanic peoples. Still later, Frankish rulers were given recognition by the Catholic Church as successors to the old rulers of the Western Roman Empire.[3][4][5][a]

Although the Frankish name does not appear until the 3rd century, at least some of the original Frankish tribes had long been known to the Romans under their own names, both as allies providing soldiers, and as enemies. The new name first appears when the Romans and their allies were losing control of the Rhine region. The Franks were first reported as working together to raid Roman territory. However, from the beginning the Franks also suffered attacks upon them from outside their frontier area, by the Saxons, for example, and as frontier tribes they desired to move into Roman territory, with which they had had centuries of close contact.

The Germanic tribes which formed the Frankish federation in Late Antiquity are associated with the Weser-Rhine Germanic/Istvaeonic cultural-linguistic grouping.[6][7][8]

Frankish peoples inside Rome's frontier on the Rhine river included the Salian Franks who from their first appearance were permitted to live in Roman territory, and the Ripuarian or Rhineland Franks who, after many attempts, eventually conquered the Roman frontier city of Cologne and took control of the left bank of the Rhine. Later, in a period of factional conflict in the 450s and 460s, Childeric I, a Frank, was one of several military leaders commanding Roman forces with various ethnic affiliations in Roman Gaul (roughly modern France). Childeric and his son Clovis I faced competition from the Roman Aegidius as competitor for the "kingship" of the Franks associated with the Roman Loire forces. (According to Gregory of Tours, Aegidius held the kingship of the Franks for 8 years while Childeric was in exile.) This new type of kingship, perhaps inspired by Alaric I,[9] represents the start of the Merovingian dynasty, which succeeded in conquering most of Gaul in the 6th century, as well as establishing its leadership over all the Frankish kingdoms on the Rhine frontier. It was on the basis of this Merovingian empire that the resurgent Carolingians eventually came to be seen as the new Emperors of Western Europe in 800.

In the High and Late Middle Ages, Western Europeans shared their allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church and worked as allies in the Crusades beyond Europe in the Levant. In 1099, the crusader population of Jerusalem mostly comprised French settlers who, at the time, were still referred to as Franks, and other Europeans such as Spaniards, Germans and Hungarians. French knights made up the bulk of the steady flow of reinforcements throughout the two-hundred-year span of the Crusades, in such a fashion that the Arabs uniformly continued to refer to the crusaders and West Europeans as Franjī caring little whether they really came from France.[10] The French Crusaders also imported the French language into the Levant, making French the base of the lingua franca (litt. "Frankish language") of the Crusader states.[10][11] This has had a lasting impact on names for Western Europeans in many languages.[12][13][14] Western Europe is known alternatively as "Frangistan" to the Persians.[15]

From the beginning the Frankish kingdoms were politically and legally divided between an eastern more Germanic part, and the western part that the Merovingians had founded on Roman soil. The eastern "Frankish" part came to be known as the new "Holy Roman Empire", and was from early times occasionally called "Germany". Within "Frankish" Western Europe itself, it was the original Merovingian or "Salian" Western Frankish kingdom, founded in Roman Gaul and speaking Romance languages, which has continued until today to be referred to as "France" – a name derived directly from the Franks.

Etymology

Main article: Name of the Franks

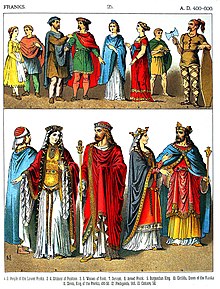

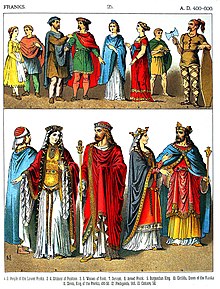

A 19th century depiction of different Franks (AD 400–600)

The name Franci was not a tribal name, but within a few centuries it had eclipsed the names of the original peoples who constituted them. Following the precedents of Edward Gibbon and Jacob Grimm,[16] the name of the Franks has been linked with the English adjective "frank", originally meaning "free".[17] There have also been proposals that Frank comes from the Germanic word for "javelin" (such as in Old English franca or Old Norse frakka).[18] Words in other Germanic languages meaning "fierce", "bold" or "insolent" (German frech, Middle Dutch vrac, Old English frǣc and Old Norwegian frakkr), may also be significant.[19]

Eumenius addressed the Franks in the matter of the execution of Frankish prisoners in the circus at Trier by Constantine I in 306 and certain other measures:[20][21] Latin: Ubi nunc est illa ferocia? Ubi semper infida mobilitas? ("Where now is that ferocity of yours? Where is that ever untrustworthy fickleness?"). Latin: Feroces was used often to describe the Franks.[22] Contemporary definitions of Frankish ethnicity vary both by period and point of view. A formulary written by Marculf about 700 AD described a continuation of national identities within a mixed population when it stated that "all the peoples who dwell [in the official's province], Franks, Romans, Burgundians and those of other nations, live ... according to their law and their custom."[23] Writing in 2009, Professor Christopher Wickham pointed out that "the word 'Frankish' quickly ceased to have an exclusive ethnic connotation. North of the River Loire everyone seems to have been considered a Frank by the mid-7th century at the latest [except Bretons]; Romani [Romans] were essentially the inhabitants of Aquitaine after that".[24]

Mythological origins

Apart from the History of the Franks by Gregory of Tours, two early sources relate the mythological origin of the Franks: a 7th-century work known as the Chronicle of Fredegar and the anonymous Liber Historiae Francorum, written a century later.

The other work, the Liber Historiae Francorum, previously known as Gesta regum Francorum before its republication in 1888 by Bruno Krusch,[27] described how 12,000 Trojans, led by Priam and Antenor, sailed from Troy to the River Don in Russia and on to Pannonia, which is on the River Danube, settling near the Sea of Azov. There they founded a city called Sicambria. (The Sicambri were the most well-known tribe in the Frankish homeland in the time of the early Roman empire, still remembered though defeated and dispersed long before the Frankish name appeared.) The Trojans joined the Roman army in accomplishing the task of driving their enemies into the marshes of Mæotis, for which they received the name of Franks (meaning "savage"). A decade later the Romans killed Priam and drove away Marcomer and Sunno, the sons of Priam and Antenor, and the other Franks.[citation needed]

History

Early history

The major primary sources on the early Franks include the Panegyrici Latini, Ammianus Marcellinus, Claudian, Zosimus, Sidonius Apollinaris and Gregory of Tours. The Franks are first mentioned in the Augustan History, a collection of biographies of the Roman emperors. None of these sources present a detailed list of which tribes or parts of tribes became Frankish, or concerning the politics and history, but to quote James (1988, p. 35):

A Roman marching-song joyfully recorded in a fourth-century source, is associated with the 260s; but the Franks' first appearance in a contemporary source was in 289. [...] The Chamavi were mentioned as a Frankish people as early as 289, the Bructeri from 307, the Chattuarri from 306–315, the Salii or Salians from 357, and the Amsivarii and Tubantes from c. 364–375.

In 288 the emperor Maximian defeated the Salian Franks, Chamavi, Frisians and other Germanic people living along the Rhine and moved them to Germania inferior to provide manpower and prevent the settlement of other Germanic tribes.[28][29] In 292 Constantius, the father of Constantine I [30] defeated the Franks who had settled at the mouth of the Rhine. These were moved to the nearby region of Toxandria.[31] Eumenius mentions Constantius as having "killed, expelled, captured [and] kidnapped" the Franks who had settled there and others who had crossed the Rhine, using the term nationes Franciae for the first time. It seems likely that the term Frank in this first period had a broader meaning, sometimes including coastal Frisians.[32]

The Franks were described in Roman texts both as allies (laeti) and enemies (dediticii). About the year 260 one group of Franks penetrated as far as Tarragona in present-day Spain, where they plagued the region for about a decade before they were subdued and expelled by the Romans. In 287 or 288, the Roman Caesar Maximian forced a Frankish leader Genobaud and his people to surrender without a fight. Maximian then forced the Salians in Toxandria (the present Low Countries) to accept imperial authority, but was not able to follow on this success by reconquering Britain.

The Life of Aurelian, which was possibly written by Vopiscus, mentions that in 328, Frankish raiders were captured by the 6th Legion stationed at Mainz. As a result of this incident, 700 Franks were killed and 300 were sold into slavery.[33][34] Frankish incursions over the Rhine became so frequent that the Romans began to settle the Franks on their borders in order to control them.

The Franks are mentioned in the Tabula Peutingeriana, an atlas of Roman roads. It is a 13th-century copy of a 4th or 5th century document that reflects information from the 3rd century. The Romans knew the shape of Europe, but their knowledge is not evident from the map, which was only a practical guide to the roads to be followed from point to point. In the middle Rhine region of the map, the word Francia is close to a misspelling of Bructeri. Beyond Mainz is Suevia, the country of the Suebi, and beyond that is Alamannia, the country of the Alamanni. Four tribes at the mouth of the Rhine are depicted: the Chauci, the Amsivarii ('Ems dwellers'), the Cherusci and the Chamavi, followed by qui et Pranci ('who are also Franks'). This implies that the Chamavi were considered Franks. The Tabula was probably based on the Orbis Pictus, a map of twenty years' labour commissioned by Augustus and then kept by the Roman's treasury department for the assessment of taxes. It did not survive as such. Information about the imperial divisions of Gaul probably derives from it.

Detail of the Tabula Peutingeriana, showing Francia at the top

Salians

Main article: Salian Franks

The Salians were first mentioned by Ammianus Marcellinus, who described Julian's defeat of "the first Franks of all, those whom custom has called the Salians," in 358.[35][36] Julian allowed the Franks to remain in Texuandria as fœderati within the Empire, having moved there from the Rhine-Maas delta.[37][38] The 5th century Notitia Dignitatum lists a group of soldiers as Salii.

Some decades later, Franks in the same region, possibly the Salians, controlled the River Scheldt and were disrupting transport links to Britain in the English Channel. Although Roman forces managed to pacify them, they failed to expel the Franks, who continued to be feared as pirates.

The Salians are generally seen as the predecessors of the Franks who pushed southwestwards into what is now modern France, who eventually came to be ruled by the Merovingians (see below). This is because when the Merovingian dynasty published the Salian law (Lex Salica) it applied in the Neustrian area from the river Liger (Loire) to the Silva Carbonaria, the western kingdom founded by them outside the original area of Frankish settlement. In the 5th century Franks under Chlodio pushed into Roman lands in and beyond the "Silva Carbonaria" or "Charcoal forest", which ran through the area of modern western Wallonia. The forest was the boundary of the original Salian territories to the north and the more Romanized area to the south in the Roman province of Belgica Secunda (roughly equivalent to what Julius Caesar had long ago called "Belgium"). Chlodio conquered Tournai, Artois, Cambrai, and as far as the Somme river. Chlodio is often seen as an ancestor of the future Merovingian dynasty. Childeric I, who according to Gregory of Tours was a reputed descendant of Chlodio, was later seen as administrative ruler over Roman Belgica Secunda and possibly other areas.[39]

Records of Childeric show him to have been active together with Roman forces in the Loire region, quite far to the south. His descendants came to rule Roman Gaul all the way to there, and this became the Frankish kingdom of Neustria, the basis of what would become medieval France. Childeric's son Clovis I also took control of the more independent Frankish kingdoms east of the Silva Carbonaria and Belgica II. This later became the Frankish kingdom of Austrasia, where the early legal code was referred to as "Ripuarian".

Ripuarians

Main article: Ripuarian Franks

Approximate location of the original Frankish tribes in the 3rd century

The Rhineland Franks who lived near the stretch of the Rhine from roughly Mainz to Duisburg, the region of the city of Cologne, are often considered separately from the Salians, and sometimes in modern texts referred to as Ripuarian Franks. The Ravenna Cosmography suggests that Francia Renensis included the old civitas of the Ubii, in Germania II (Germania Inferior), but also the northern part of Germania I (Germania Superior), including Mainz. Like the Salians they appear in Roman records both as raiders and as contributors to military units. Unlike the Salii, there is no record of when, if ever, the empire officially accepted their residence within the empire. They eventually succeeded to hold the city of Cologne, and at some point seem to have acquired the name Ripuarians, which may have meant "river people". In any case a Merovingian legal code was called the Lex Ribuaria, but it probably applied in all the older Frankish lands, including the original Salian areas.

Jordanes, in Getica mentions the Riparii as auxiliaries of Flavius Aetius during the Battle of Châlons in 451: "Hi enim affuerunt auxiliares: Franci, Sarmatae, Armoriciani, Liticiani, Burgundiones, Saxones, Riparii, Olibriones ..." [40] But these Riparii ("river dwellers") are today not considered to be Ripuarian Franks, but a known military unit based on the river Rhone.[41]

Their territory on both sides of the Rhine became a central part of Merovingian Austrasia, which stretched to include Roman Germania Inferior (later Germania Secunda, which included the original Salian and Ripuarian lands, and roughly equates to medieval Lower Lotharingia) as well as Gallia Belgica Prima (late Roman "Belgium", roughly medieval Upper Lotharingia), and lands on the east bank of the Rhine.

Merovingian kingdom (481–751)

Main article: Merovingian dynasty

A 6th–7th century necklace of glass and ceramic beads with a central amethyst bead. Similar necklaces have been found in the graves of Frankish women in the Rhineland.

A 6th century bow fibula found in north-eastern France and the Rhineland. They were worn by Frankish noblewomen in pairs at the shoulder or as belt ornaments.

Gregory of Tours (Book II) reported that small Frankish kingdoms existed during the fifth century around Cologne, Tournai, Cambrai and elsewhere. The kingdom of the Merovingians eventually came to dominate the others, possibly because of its association with Roman power structures in northern Gaul, which the Frankish military forces were apparently integrated into to some extent. Aegidius, was originally the magister militum of northern Gaul appointed by Majorian, but after Majorian's death apparently seen as a Roman rebel who relied on Frankish forces. Gregory of Tours reported that Childeric I was exiled for 8 years while Aegidius held the title of "King of the Franks". Eventually Childeric returned and took the same title. Aegidius died in 464 or 465.[42] Childeric and his son Clovis I were both described as rulers of the Roman Province of Belgica Secunda, by its spiritual leader in the time of Clovis, Saint Remigius.

Clovis later defeated the son of Aegidius, Syagrius, in 486 or 487 and then had the Frankish king Chararic imprisoned and executed. A few years later, he killed Ragnachar, the Frankish king of Cambrai, and his brothers. After conquering the Kingdom of Soissons and expelling the Visigoths from southern Gaul at the Battle of Vouillé, he established Frankish hegemony over most of Gaul, excluding Burgundy, Provence and Brittany, which were eventually absorbed by his successors. By the 490s, he had conquered all the Frankish kingdoms to the west of the River Maas except for the Ripuarian Franks and was in a position to make the city of Paris his capital. He became the first king of all Franks in 509, after he had conquered Cologne.

Clovis I divided his realm between his four sons, who united to defeat Burgundy in 534. Internecine feuding occurred during the reigns of the brothers Sigebert I and Chilperic I, which was largely fuelled by the rivalry of their queens, Brunhilda and Fredegunda, and which continued during the reigns of their sons and their grandsons. Three distinct subkingdoms emerged: Austrasia, Neustria and Burgundy, each of which developed independently and sought to exert influence over the others. The influence of the Arnulfing clan of Austrasia ensured that the political centre of gravity in the kingdom gradually shifted eastwards to the Rhineland.

The Frankish realm was reunited in 613 by Chlothar II, the son of Chilperic, who granted his nobles the Edict of Paris in an effort to reduce corruption and reassert his authority. Following the military successes of his son and successor Dagobert I, royal authority rapidly declined under a series of kings, traditionally known as les rois fainéants. After the Battle of Tertry in 687, each mayor of the palace, who had formerly been the king's chief household official, effectively held power until in 751, with the approval of the Pope and the nobility, Pepin the Short deposed the last Merovingian king Childeric III and had himself crowned. This inaugurated a new dynasty, the Carolingians.

Carolingian empire (751–843)

Main article: Carolingian Empire

The unification achieved by the Merovingians ensured the continuation of what has become known as the Carolingian Renaissance. The Carolingian Empire was beset by internecine warfare, but the combination of Frankish rule and Roman Christianity ensured that it was fundamentally united. Frankish government and culture depended very much upon each ruler and his aims and so each region of the empire developed differently. Although a ruler's aims depended upon the political alliances of his family, the leading families of Francia shared the same basic beliefs and ideas of government, which had both Roman and Germanic roots.[citation needed]

The Frankish state consolidated its hold over the majority of western Europe by the end of the 8th century, developing into the Carolingian Empire. With the coronation of their ruler Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III in 800 AD, he and his successors were recognised as legitimate successors to the emperors of the Western Roman Empire. As such, the Carolingian Empire gradually came to be seen in the West as a continuation of the ancient Roman Empire. This empire would give rise to several successor states, including France, the Holy Roman Empire and Burgundy, though the Frankish identity remained most closely identified with France.

After the death of Charlemagne, his only adult surviving son became Emperor and King Louis the Pious. Following Louis the Pious's death, however, according to Frankish culture and law that demanded equality among all living male adult heirs, the Frankish Empire was now split between Louis' three sons.

Military

Participation in the Roman army

Germanic peoples, including those tribes in the Rhine delta that later became the Franks, are known to have served in the Roman army since the days of Julius Caesar. After the Roman administration collapsed in Gaul in the 260s, the armies under the Germanic Batavian Postumus revolted and proclaimed him emperor and then restored order. From then on, Germanic soldiers in the Roman army, most notably Franks, were promoted from the ranks. A few decades later, the Menapian Carausius created a Batavian–British rump state on Roman soil that was supported by Frankish soldiers and raiders. Frankish soldiers such as Magnentius, Silvanus and Arbitio held command positions in the Roman army during the mid 4th century. From the narrative of Ammianus Marcellinus it is evident that both Frankish and Alamannic tribal armies were organised along Roman lines.

After the invasion of Chlodio, the Roman armies at the Rhine border became a Frankish "franchise" and Franks were known to levy Roman-like troops that were supported by a Roman-like armour and weapons industry. This lasted at least until the days of the scholar Procopius (c. 500 – c. 565), more than a century after the demise of the Western Roman Empire, who wrote describing the former Arborychoi, having merged with the Franks, retaining their legionary organization in the style of their forefathers during Roman times. The Franks under the Merovingians melded Germanic custom with Romanised organisation and several important tactical innovations. Before their conquest of Gaul, the Franks fought primarily as a tribe, unless they were part of a Roman military unit fighting in conjunction with other imperial units.

Military practices of the early Franks

The primary sources for Frankish military custom and armament are Ammianus Marcellinus, Agathias and Procopius, the latter two Eastern Roman historians writing about Frankish intervention in the Gothic War.

Writing of 539, Procopius says:

The frontispiece of Gregory's Historia Francorum

The evidence of Gregory and of the Lex Salica implies that the early Franks were a cavalry people. In fact, some modern historians have hypothesised that the Franks possessed so numerous a body of horses that they could use them to plough fields and thus were agriculturally technologically advanced over their neighbours. The Lex Ribuaria specifies that a mare's value was the same as that of an ox or of a shield and spear, two solidi and a stallion seven or the same as a sword and scabbard,[45] which suggests that horses were relatively common. Perhaps the Byzantine writers considered the Frankish horse to be insignificant relative to the Greek cavalry, which is probably accurate.[46]

Merovingian military

Composition and development

The Frankish military establishment incorporated many of the pre-existing Roman institutions in Gaul, especially during and after the conquests of Clovis I in the late 5th and early 6th centuries. Frankish military strategy revolved around the holding and taking of fortified centres (castra) and in general these centres were held by garrisons of milities or laeti, who were former Roman mercenaries of Germanic origin. Throughout Gaul, the descendants of Roman soldiers continued to wear their uniforms and perform their ceremonial duties.

Immediately beneath the Frankish king in the military hierarchy were the leudes, his sworn followers, who were generally 'old soldiers' in service away from court.[47] The king had an elite bodyguard called the truste. Members of the truste often served in centannae, garrison settlements that were established for military and police purposes. The day-to-day bodyguard of the king was made up of antrustiones (senior soldiers who were aristocrats in military service) and pueri (junior soldiers and not aristocrats).[48] All high-ranking men had pueri.

The Frankish military was not composed solely of Franks and Gallo-Romans, but also contained Saxons, Alans, Taifals and Alemanni. After the conquest of Burgundy (534), the well-organised military institutions of that kingdom were integrated into the Frankish realm. Chief among these was the standing army under the command of the Patrician of Burgundy.

In the late 6th century, during the wars instigated by Fredegund and Brunhilda, the Merovingian monarchs introduced a new element into their militaries: the local levy. A levy consisted of all the able-bodied men of a district who were required to report for military service when called upon, similar to conscription. The local levy applied only to a city and its environs. Initially only in certain cities in western Gaul, in Neustria and Aquitaine, did the kings possess the right or power to call up the levy. The commanders of the local levies were always different from the commanders of the urban garrisons. Often the former were commanded by the counts of the districts. A much rarer occurrence was the general levy, which applied to the entire kingdom and included peasants (pauperes and inferiores). General levies could also be made within the still-pagan trans-Rhenish stem duchies on the orders of a monarch. The Saxons, Alemanni and Thuringii all had the institution of the levy and the Frankish monarchs could depend upon their levies until the mid-7th century, when the stem dukes began to sever their ties to the monarchy. Radulf of Thuringia called up the levy for a war against Sigebert III in 640.

Soon the local levy spread to Austrasia and the less Romanised regions of Gaul. On an intermediate level, the kings began calling up territorial levies from the regions of Austrasia (which did not have major cities of Roman origin). All the forms of the levy gradually disappeared, however, in the course of the 7th century after the reign of Dagobert I. Under the so-called rois fainéants, the levies disappeared by mid-century in Austrasia and later in Burgundy and Neustria. Only in Aquitaine, which was fast becoming independent of the central Frankish monarchy, did complex military institutions persist into the 8th century. In the final half of the 7th century and first half of the 8th in Merovingian Gaul, the chief military actors became the lay and ecclesiastical magnates with their bands of armed followers called retainers. The other aspects of the Merovingian military, mostly Roman in origin or innovations of powerful kings, disappeared from the scene by the 8th century.

Strategy, tactics and equipment

Merovingian armies used coats of mail, helmets, shields, lances, swords, bows and arrows and war horses. The armament of private armies resembled those of the Gallo-Roman potentiatores of the late Empire. A strong element of Alanic cavalry settled in Armorica influenced the fighting style of the Bretons down into the 12th century. Local urban levies could be reasonably well-armed and even mounted, but the more general levies were composed of pauperes and inferiores, who were mostly farmers by trade and carried ineffective weapons, such as farming implements. The peoples east of the Rhine – Franks, Saxons and even Wends – who were sometimes called upon to serve, wore rudimentary armour and carried weapons such as spears and axes. Few of these men were mounted.[citation needed]

Merovingian society had a militarised nature. The Franks called annual meetings every Marchfeld (1 March), when the king and his nobles assembled in large open fields and determined their targets for the next campaigning season. The meetings were a show of strength on behalf of the monarch and a way for him to retain loyalty among his troops.[49] In their civil wars, the Merovingian kings concentrated on the holding of fortified places and the use of siege engines. In wars waged against external foes, the objective was typically the acquisition of booty or the enforcement of tribute. Only in the lands beyond the Rhine did the Merovingians seek to extend political control over their neighbours.

Tactically, the Merovingians borrowed heavily from the Romans, especially regarding siege warfare. Their battle tactics were highly flexible and were designed to meet the specific circumstances of a battle. The tactic of subterfuge was employed endlessly. Cavalry formed a large segment of an army[citation needed], but troops readily dismounted to fight on foot. The Merovingians were capable of raising naval forces: the naval campaign waged against the Danes by Theuderic I in 515 involved ocean-worthy ships and rivercraft were used on the Loire, Rhône and Rhine.

Culture

Language

Main article: Frankish language

In a modern linguistic context, the language of the early Franks is variously called "Old Frankish" or "Old Franconian" and refers to the West Germanic dialects of the Franks prior to the advent of the Second Germanic consonant shift, which took place between 600 and 700. After this consonant shift the Frankish dialect diverges, with the dialects that would become modern Dutch not undergoing the consonantal shift, while all others did so to varying degrees and thereby became part of the larger German dialectal domain.[50]

The Frankish language has not been directly attested, apart from a very small number of runic inscriptions found within contemporary Frankish territory such as the Bergakker inscription. The distinction between Old Dutch and Old Frankish is largely negligible, with Old Dutch (also called Old Low Franconian) being the term used to differentiate between the affected and non-affected variants following the aforementioned Second Germanic consonant shift.[51]

A significant amount of Old Frankish vocabulary has been reconstructed by examining early Germanic loanwords found in Old French as well as through comparative reconstruction through Dutch.[52][53] The influence of Old Frankish on contemporary Gallo-Roman vocabulary and phonology, have long been questions of scholarly debate.[54] Frankish influence is thought to include the designations of the four cardinal directions: nord "north", sud "south", est "east" and ouest "west" and at least an additional 1000 stem words.[53]

Although the Franks would eventually conquer all of Gaul, speakers of Old Franconian apparently expanded in sufficient numbers only into northern Gaul to have a linguistic effect. For several centuries, northern Gaul was a bilingual territory (Vulgar Latin and Franconian). The language used in writing, in government and by the Church was Latin. Urban T. Holmes has proposed that a Germanic language continued to be spoken as a second tongue by public officials in western Austrasia and Northern Neustria as late as the 850s, and that it completely disappeared as a spoken language during the 10th century from regions where only French is spoken today.[55]

Art and architecture

A chalice from the Treasure of Gourdon.

The pinnacle of Carolingian architecture: The Palatine chapel at Aachen, Germany.

Main articles: Merovingian art and architecture and Carolingian art

Early Frankish art and architecture belongs to a phase known as Migration Period art, which has left very few remains. The later period is called Carolingian art, or, especially in architecture, pre-Romanesque. Very little Merovingian architecture has been preserved. The earliest churches seem to have been timber-built, with larger examples being of a basilica type. The most completely surviving example, a baptistery in Poitiers, is a building with three apses of a Gallo-Roman style. A number of small baptistries can be seen in Southern France: as these fell out of fashion, they were not updated and have subsequently survived as they were.

Jewelry (such as brooches), weapons (including swords with decorative hilts) and clothing (such as capes and sandals) have been found in a number of grave sites. The grave of Queen Aregund, discovered in 1959, and the Treasure of Gourdon, which was deposited soon after 524, are notable examples. The few Merovingian illuminated manuscripts that have survived, such as the Gelasian Sacramentary, contain a great deal of zoomorphic representations. Such Frankish objects show a greater use of the style and motifs of Late Antiquity and a lesser degree of skill and sophistication in design and manufacture than comparable works from the British Isles. So little has survived, however, that the best quality of work from this period may not be represented.[56]

The objects produced by the main centres of the Carolingian Renaissance, which represent a transformation from that of the earlier period, have survived in far greater quantity. The arts were lavishly funded and encouraged by Charlemagne, using imported artists where necessary, and Carolingian developments were decisive for the future course of Western art. Carolingian illuminated manuscripts and ivory plaques, which have survived in reasonable numbers, approached those of Constantinople in quality. The main surviving monument of Carolingian architecture is the Palatine Chapel in Aachen, which is an impressive and confident adaptation of San Vitale, Ravenna – from where some of the pillars were brought. Many other important buildings existed, such as the monasteries of Centula or St Gall, or the old Cologne Cathedral, since rebuilt. These large structures and complexes made frequent use of towers.[57]

Religion

A sizeable portion of the Frankish aristocracy quickly followed Clovis in converting to Christianity (the Frankish church of the Merovingians). The conversion of all under Frankish rule required a considerable amount of time and effort.

Paganism

Main article: Frankish mythology

Drawing of golden bees or flies that was discovered in the tomb of Childeric I

Echoes of Frankish paganism can be found in the primary sources, but their meaning is not always clear. Interpretations by modern scholars differ greatly, but it is likely that Frankish paganism shared most of the characteristics of other varieties of Germanic paganism. The mythology of the Franks was probably a form of Germanic polytheism. It was highly ritualistic. Many daily activities centred around the multiple deities, chiefest of which may have been the Quinotaur, a water-god from whom the Merovingians were reputed to have derived their ancestry.[58] Most of their gods were linked with local cult centres and their sacred character and power were associated with specific regions, outside of which they were neither worshipped nor feared. Most of the gods were "worldly", possessing form and having connections with specific objects, in contrast to the God of Christianity.[59]

Frankish paganism has been observed in the burial site of Childeric I, where the king's body was found covered in a cloth decorated with numerous bees. There is a likely connection with the bees to the traditional Frankish weapon, the angon (meaning "sting"), from its distinctive spearhead. It is possible that the fleur-de-lis is derived from the angon.

Christianity

Statue in the Basilica of Saint-Remi depicting the baptism of Clovis I by Saint Remi in around 496

Further information: Christianity in Merovingian Gaul and Frankish Church

Some Franks, like the 4th century usurper Silvanus, converted early to Christianity. In 496, Clovis I, who had married a Burgundian Catholic named Clotilda in 493, was baptised by Saint Remi after a decisive victory over the Alemanni at the Battle of Tolbiac. According to Gregory of Tours, over three thousand of his soldiers were baptised with him.[60] Clovis' conversion had a profound effect on the course of European history, for at the time the Franks were the only major Christianised Germanic tribe without a predominantly Arian aristocracy and this led to a naturally amicable relationship between the Catholic Church and the increasingly powerful Franks.

Although many of the Frankish aristocracy quickly followed Clovis in converting to Christianity, the conversion of all his subjects was only achieved after considerable effort and, in some regions, a period of over two centuries.[61] The Chronicle of St. Denis relates that, following Clovis' conversion, a number of pagans who were unhappy with this turn of events rallied around Ragnachar, who had played an important role in Clovis' initial rise to power. Although the text remains unclear as to the precise pretext, Clovis had Ragnachar executed.[62] Remaining pockets of resistance were overcome region by region, primarily due to the work of an expanding network of monasteries.[63]

Gelasian Sacramentary, c. 750

The Merovingian Church was shaped by both internal and external forces. It had to come to terms with an established Gallo-Roman hierarchy that resisted changes to its culture, Christianise pagan sensibilities and suppress their expression, provide a new theological basis for Merovingian forms of kingship deeply rooted in pagan Germanic tradition and accommodate Irish and Anglo-Saxon missionary activities and papal requirements.[64] The Carolingian reformation of monasticism and church-state relations was the culmination of the Frankish Church.

The increasingly wealthy Merovingian elite endowed many monasteries, including that of the Irish missionary Columbanus. The 5th, 6th and 7th centuries saw two major waves of hermitism in the Frankish world, which led to legislation requiring that all monks and hermits follow the Rule of St Benedict.[65] The Church sometimes had an uneasy relationship with the Merovingian kings, whose claim to rule depended on a mystique of royal descent and who tended to revert to the polygamy of their pagan ancestors. Rome encouraged the Franks to slowly replace the Gallican Rite with the Roman rite. When the mayors took over, the Church was supportive and an Emperor crowned by the Pope was much more to their liking.

Laws

As with other Germanic peoples, the laws of the Franks were memorised by "rachimburgs", who were analogous to the lawspeakers of Scandinavia.[66] By the 6th century, when these laws first appeared in written form, two basic legal subdivisions existed: Salian Franks were subject to Salic law and Ripuarian Franks to Ripuarian law. Gallo-Romans south of the River Loire and the clergy remained subject to traditional Roman law.[67] Germanic law was overwhelmingly concerned with the protection of individuals and less concerned with protecting the interests of the state. According to Michel Rouche, "Frankish judges devoted as much care to a case involving the theft of a dog as Roman judges did to cases involving the fiscal responsibility of curiales, or municipal councilors".[68]

Legacy

Further information: Name of the Franks

Carolingian Empire (green) in 814

The term Frank has been used by many of the Eastern Orthodox and Muslim neighbours of medieval Latin Christendom (and beyond, such as in Asia) as a general synonym for a European from Western and Central Europe, areas that followed the Latin rites of Christianity under the authority of the Pope in Rome.[69] Another term with similar use was Latins.

Modern historians often refer to Christians following the Latin rites in the eastern Mediterranean as Franks or Latins, regardless of their country of origin, whereas they use the words Rhomaios and Rûmi ("Roman") for Orthodox Christians. On a number of Greek islands, Catholics are still referred to as Φράγκοι (Frangoi) or "Franks", for instance on Syros, where they are called Φραγκοσυριανοί (Frangosyrianoi). The period of Crusader rule in Greek lands is known to this day as the Frankokratia ("rule of the Franks"). Latin Christians living in the Middle East (particularly in the Levant) are known as Franco-Levantines.

During the Mongol Empire in the 13-14th centuries, the Mongols used the term "Franks" to designate Europeans.[70] The term Frangistan ("Land of the Franks") was used by Muslims to refer to Christian Europe and was commonly used over several centuries in Iran and the Ottoman Empire.

The Chinese called the Portuguese Folangji 佛郎機 ("Franks") in the 1520s at the Battle of Tunmen and Battle of Xicaowan. Some other varieties of Mandarin Chinese pronounced the characters as Fah-lan-ki.

Examples of derived words include:

In the Thai usage, the word can refer to any European person. When the presence of US soldiers during the Vietnam War placed Thai people in contact with African Americans, they (and people of African ancestry in general) came to be called Farang dam ("Black Farang", ฝรั่งดำ). Such words sometimes also connote things, plants or creatures introduced by Europeans/Franks. For example, in Khmer, môn barang, literally "French Chicken", refers to a turkey and in Thai, Farang is the name both for Europeans and for the guava fruit, introduced by Portuguese traders over 400 years ago. In contemporary Israel, the Yiddish[citation needed] word פרענק (Frenk) has, by a curious etymological development, come to refer to Mizrahi Jews and carries a strong pejorative connotation.

Some linguists (among them Drs. Jan Tent and Paul Geraghty) have suggested that the Samoan and generic Polynesian term for Europeans, Palagi (pronounced Puh-LANG-ee) or Papalagi, might also be cognate, possibly a loan term gathered by early contact between Pacific islanders and Malays.[77]

| Related ethnic groups |

|---|

| Religion |

| Languages |

| Franci |

Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian period |

| Old Frankish |

| Frankish paganism, Catholic Christianity |

| Germanic peoples, French people |

Although the Frankish name does not appear until the 3rd century, at least some of the original Frankish tribes had long been known to the Romans under their own names, both as allies providing soldiers, and as enemies. The new name first appears when the Romans and their allies were losing control of the Rhine region. The Franks were first reported as working together to raid Roman territory. However, from the beginning the Franks also suffered attacks upon them from outside their frontier area, by the Saxons, for example, and as frontier tribes they desired to move into Roman territory, with which they had had centuries of close contact.

The Germanic tribes which formed the Frankish federation in Late Antiquity are associated with the Weser-Rhine Germanic/Istvaeonic cultural-linguistic grouping.[6][7][8]

Frankish peoples inside Rome's frontier on the Rhine river included the Salian Franks who from their first appearance were permitted to live in Roman territory, and the Ripuarian or Rhineland Franks who, after many attempts, eventually conquered the Roman frontier city of Cologne and took control of the left bank of the Rhine. Later, in a period of factional conflict in the 450s and 460s, Childeric I, a Frank, was one of several military leaders commanding Roman forces with various ethnic affiliations in Roman Gaul (roughly modern France). Childeric and his son Clovis I faced competition from the Roman Aegidius as competitor for the "kingship" of the Franks associated with the Roman Loire forces. (According to Gregory of Tours, Aegidius held the kingship of the Franks for 8 years while Childeric was in exile.) This new type of kingship, perhaps inspired by Alaric I,[9] represents the start of the Merovingian dynasty, which succeeded in conquering most of Gaul in the 6th century, as well as establishing its leadership over all the Frankish kingdoms on the Rhine frontier. It was on the basis of this Merovingian empire that the resurgent Carolingians eventually came to be seen as the new Emperors of Western Europe in 800.

In the High and Late Middle Ages, Western Europeans shared their allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church and worked as allies in the Crusades beyond Europe in the Levant. In 1099, the crusader population of Jerusalem mostly comprised French settlers who, at the time, were still referred to as Franks, and other Europeans such as Spaniards, Germans and Hungarians. French knights made up the bulk of the steady flow of reinforcements throughout the two-hundred-year span of the Crusades, in such a fashion that the Arabs uniformly continued to refer to the crusaders and West Europeans as Franjī caring little whether they really came from France.[10] The French Crusaders also imported the French language into the Levant, making French the base of the lingua franca (litt. "Frankish language") of the Crusader states.[10][11] This has had a lasting impact on names for Western Europeans in many languages.[12][13][14] Western Europe is known alternatively as "Frangistan" to the Persians.[15]

From the beginning the Frankish kingdoms were politically and legally divided between an eastern more Germanic part, and the western part that the Merovingians had founded on Roman soil. The eastern "Frankish" part came to be known as the new "Holy Roman Empire", and was from early times occasionally called "Germany". Within "Frankish" Western Europe itself, it was the original Merovingian or "Salian" Western Frankish kingdom, founded in Roman Gaul and speaking Romance languages, which has continued until today to be referred to as "France" – a name derived directly from the Franks.

Etymology

Main article: Name of the Franks

A 19th century depiction of different Franks (AD 400–600)

The name Franci was not a tribal name, but within a few centuries it had eclipsed the names of the original peoples who constituted them. Following the precedents of Edward Gibbon and Jacob Grimm,[16] the name of the Franks has been linked with the English adjective "frank", originally meaning "free".[17] There have also been proposals that Frank comes from the Germanic word for "javelin" (such as in Old English franca or Old Norse frakka).[18] Words in other Germanic languages meaning "fierce", "bold" or "insolent" (German frech, Middle Dutch vrac, Old English frǣc and Old Norwegian frakkr), may also be significant.[19]

Eumenius addressed the Franks in the matter of the execution of Frankish prisoners in the circus at Trier by Constantine I in 306 and certain other measures:[20][21] Latin: Ubi nunc est illa ferocia? Ubi semper infida mobilitas? ("Where now is that ferocity of yours? Where is that ever untrustworthy fickleness?"). Latin: Feroces was used often to describe the Franks.[22] Contemporary definitions of Frankish ethnicity vary both by period and point of view. A formulary written by Marculf about 700 AD described a continuation of national identities within a mixed population when it stated that "all the peoples who dwell [in the official's province], Franks, Romans, Burgundians and those of other nations, live ... according to their law and their custom."[23] Writing in 2009, Professor Christopher Wickham pointed out that "the word 'Frankish' quickly ceased to have an exclusive ethnic connotation. North of the River Loire everyone seems to have been considered a Frank by the mid-7th century at the latest [except Bretons]; Romani [Romans] were essentially the inhabitants of Aquitaine after that".[24]

Mythological origins

Apart from the History of the Franks by Gregory of Tours, two early sources relate the mythological origin of the Franks: a 7th-century work known as the Chronicle of Fredegar and the anonymous Liber Historiae Francorum, written a century later.

The author of the Chronicle of Fredegar claimed that the Franks came originally from Troy and quoted the works of Virgil and Hieronymous:Many say that the Franks originally came from Pannonia and first inhabited the banks of the Rhine. Then they crossed the river, marched through Thuringia, and set up in each county district and each city longhaired kings chosen from their foremost and most noble family.

— Gregory of Tours, History of the Franks (6th c. CE)[25]

According to historian Patrick J. Geary, those two mythological stories are "alike in betraying both the fact that the Franks knew little about their background and that they may have felt some inferiority in comparison with other peoples of antiquity who possessed an ancient name and glorious tradition. (...) Both legends are of course equally fabulous for, even more than most barbarian peoples, the Franks possessed no common history, ancestry, or tradition of a heroic age of migration. Like their Alemannic neighbours, they were by the sixth century a fairly recent creation, a coalition of Rhenish tribal groups who long maintained separate identities and institutions."[26]Blessed Jerome has written about the ancient kings of the Franks, whose story was first told by the poet Virgil: their first king was Priam and, after Troy was captured by trickery, they departed. Afterwards they had as king Friga, then they split into two parts, the first going into Macedonia, the second group, which left Asia with Friga were called the Frigii, settled on the banks of the Danube and the Ocean Sea. Again splitting into, two groups, half of them entered Europe with their king Francio. After crossing Europe with their wives and children they occupied the banks of the Rhine and not far from the Rhine began to build the city of "Troy" (Colonia Traiana-Xanten).

— Fredegar, Chronicle of Fredegar (7th c. CE)[25]

The other work, the Liber Historiae Francorum, previously known as Gesta regum Francorum before its republication in 1888 by Bruno Krusch,[27] described how 12,000 Trojans, led by Priam and Antenor, sailed from Troy to the River Don in Russia and on to Pannonia, which is on the River Danube, settling near the Sea of Azov. There they founded a city called Sicambria. (The Sicambri were the most well-known tribe in the Frankish homeland in the time of the early Roman empire, still remembered though defeated and dispersed long before the Frankish name appeared.) The Trojans joined the Roman army in accomplishing the task of driving their enemies into the marshes of Mæotis, for which they received the name of Franks (meaning "savage"). A decade later the Romans killed Priam and drove away Marcomer and Sunno, the sons of Priam and Antenor, and the other Franks.[citation needed]

History

Early history

The major primary sources on the early Franks include the Panegyrici Latini, Ammianus Marcellinus, Claudian, Zosimus, Sidonius Apollinaris and Gregory of Tours. The Franks are first mentioned in the Augustan History, a collection of biographies of the Roman emperors. None of these sources present a detailed list of which tribes or parts of tribes became Frankish, or concerning the politics and history, but to quote James (1988, p. 35):

A Roman marching-song joyfully recorded in a fourth-century source, is associated with the 260s; but the Franks' first appearance in a contemporary source was in 289. [...] The Chamavi were mentioned as a Frankish people as early as 289, the Bructeri from 307, the Chattuarri from 306–315, the Salii or Salians from 357, and the Amsivarii and Tubantes from c. 364–375.

In 288 the emperor Maximian defeated the Salian Franks, Chamavi, Frisians and other Germanic people living along the Rhine and moved them to Germania inferior to provide manpower and prevent the settlement of other Germanic tribes.[28][29] In 292 Constantius, the father of Constantine I [30] defeated the Franks who had settled at the mouth of the Rhine. These were moved to the nearby region of Toxandria.[31] Eumenius mentions Constantius as having "killed, expelled, captured [and] kidnapped" the Franks who had settled there and others who had crossed the Rhine, using the term nationes Franciae for the first time. It seems likely that the term Frank in this first period had a broader meaning, sometimes including coastal Frisians.[32]

The Franks were described in Roman texts both as allies (laeti) and enemies (dediticii). About the year 260 one group of Franks penetrated as far as Tarragona in present-day Spain, where they plagued the region for about a decade before they were subdued and expelled by the Romans. In 287 or 288, the Roman Caesar Maximian forced a Frankish leader Genobaud and his people to surrender without a fight. Maximian then forced the Salians in Toxandria (the present Low Countries) to accept imperial authority, but was not able to follow on this success by reconquering Britain.

The Life of Aurelian, which was possibly written by Vopiscus, mentions that in 328, Frankish raiders were captured by the 6th Legion stationed at Mainz. As a result of this incident, 700 Franks were killed and 300 were sold into slavery.[33][34] Frankish incursions over the Rhine became so frequent that the Romans began to settle the Franks on their borders in order to control them.

The Franks are mentioned in the Tabula Peutingeriana, an atlas of Roman roads. It is a 13th-century copy of a 4th or 5th century document that reflects information from the 3rd century. The Romans knew the shape of Europe, but their knowledge is not evident from the map, which was only a practical guide to the roads to be followed from point to point. In the middle Rhine region of the map, the word Francia is close to a misspelling of Bructeri. Beyond Mainz is Suevia, the country of the Suebi, and beyond that is Alamannia, the country of the Alamanni. Four tribes at the mouth of the Rhine are depicted: the Chauci, the Amsivarii ('Ems dwellers'), the Cherusci and the Chamavi, followed by qui et Pranci ('who are also Franks'). This implies that the Chamavi were considered Franks. The Tabula was probably based on the Orbis Pictus, a map of twenty years' labour commissioned by Augustus and then kept by the Roman's treasury department for the assessment of taxes. It did not survive as such. Information about the imperial divisions of Gaul probably derives from it.

Detail of the Tabula Peutingeriana, showing Francia at the top

Salians

Main article: Salian Franks

The Salians were first mentioned by Ammianus Marcellinus, who described Julian's defeat of "the first Franks of all, those whom custom has called the Salians," in 358.[35][36] Julian allowed the Franks to remain in Texuandria as fœderati within the Empire, having moved there from the Rhine-Maas delta.[37][38] The 5th century Notitia Dignitatum lists a group of soldiers as Salii.

Some decades later, Franks in the same region, possibly the Salians, controlled the River Scheldt and were disrupting transport links to Britain in the English Channel. Although Roman forces managed to pacify them, they failed to expel the Franks, who continued to be feared as pirates.

The Salians are generally seen as the predecessors of the Franks who pushed southwestwards into what is now modern France, who eventually came to be ruled by the Merovingians (see below). This is because when the Merovingian dynasty published the Salian law (Lex Salica) it applied in the Neustrian area from the river Liger (Loire) to the Silva Carbonaria, the western kingdom founded by them outside the original area of Frankish settlement. In the 5th century Franks under Chlodio pushed into Roman lands in and beyond the "Silva Carbonaria" or "Charcoal forest", which ran through the area of modern western Wallonia. The forest was the boundary of the original Salian territories to the north and the more Romanized area to the south in the Roman province of Belgica Secunda (roughly equivalent to what Julius Caesar had long ago called "Belgium"). Chlodio conquered Tournai, Artois, Cambrai, and as far as the Somme river. Chlodio is often seen as an ancestor of the future Merovingian dynasty. Childeric I, who according to Gregory of Tours was a reputed descendant of Chlodio, was later seen as administrative ruler over Roman Belgica Secunda and possibly other areas.[39]

Records of Childeric show him to have been active together with Roman forces in the Loire region, quite far to the south. His descendants came to rule Roman Gaul all the way to there, and this became the Frankish kingdom of Neustria, the basis of what would become medieval France. Childeric's son Clovis I also took control of the more independent Frankish kingdoms east of the Silva Carbonaria and Belgica II. This later became the Frankish kingdom of Austrasia, where the early legal code was referred to as "Ripuarian".

Ripuarians

Main article: Ripuarian Franks

Approximate location of the original Frankish tribes in the 3rd century

The Rhineland Franks who lived near the stretch of the Rhine from roughly Mainz to Duisburg, the region of the city of Cologne, are often considered separately from the Salians, and sometimes in modern texts referred to as Ripuarian Franks. The Ravenna Cosmography suggests that Francia Renensis included the old civitas of the Ubii, in Germania II (Germania Inferior), but also the northern part of Germania I (Germania Superior), including Mainz. Like the Salians they appear in Roman records both as raiders and as contributors to military units. Unlike the Salii, there is no record of when, if ever, the empire officially accepted their residence within the empire. They eventually succeeded to hold the city of Cologne, and at some point seem to have acquired the name Ripuarians, which may have meant "river people". In any case a Merovingian legal code was called the Lex Ribuaria, but it probably applied in all the older Frankish lands, including the original Salian areas.

Jordanes, in Getica mentions the Riparii as auxiliaries of Flavius Aetius during the Battle of Châlons in 451: "Hi enim affuerunt auxiliares: Franci, Sarmatae, Armoriciani, Liticiani, Burgundiones, Saxones, Riparii, Olibriones ..." [40] But these Riparii ("river dwellers") are today not considered to be Ripuarian Franks, but a known military unit based on the river Rhone.[41]

Their territory on both sides of the Rhine became a central part of Merovingian Austrasia, which stretched to include Roman Germania Inferior (later Germania Secunda, which included the original Salian and Ripuarian lands, and roughly equates to medieval Lower Lotharingia) as well as Gallia Belgica Prima (late Roman "Belgium", roughly medieval Upper Lotharingia), and lands on the east bank of the Rhine.

Merovingian kingdom (481–751)

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Main article: Merovingian dynasty

A 6th–7th century necklace of glass and ceramic beads with a central amethyst bead. Similar necklaces have been found in the graves of Frankish women in the Rhineland.

A 6th century bow fibula found in north-eastern France and the Rhineland. They were worn by Frankish noblewomen in pairs at the shoulder or as belt ornaments.

Gregory of Tours (Book II) reported that small Frankish kingdoms existed during the fifth century around Cologne, Tournai, Cambrai and elsewhere. The kingdom of the Merovingians eventually came to dominate the others, possibly because of its association with Roman power structures in northern Gaul, which the Frankish military forces were apparently integrated into to some extent. Aegidius, was originally the magister militum of northern Gaul appointed by Majorian, but after Majorian's death apparently seen as a Roman rebel who relied on Frankish forces. Gregory of Tours reported that Childeric I was exiled for 8 years while Aegidius held the title of "King of the Franks". Eventually Childeric returned and took the same title. Aegidius died in 464 or 465.[42] Childeric and his son Clovis I were both described as rulers of the Roman Province of Belgica Secunda, by its spiritual leader in the time of Clovis, Saint Remigius.

Clovis later defeated the son of Aegidius, Syagrius, in 486 or 487 and then had the Frankish king Chararic imprisoned and executed. A few years later, he killed Ragnachar, the Frankish king of Cambrai, and his brothers. After conquering the Kingdom of Soissons and expelling the Visigoths from southern Gaul at the Battle of Vouillé, he established Frankish hegemony over most of Gaul, excluding Burgundy, Provence and Brittany, which were eventually absorbed by his successors. By the 490s, he had conquered all the Frankish kingdoms to the west of the River Maas except for the Ripuarian Franks and was in a position to make the city of Paris his capital. He became the first king of all Franks in 509, after he had conquered Cologne.

Clovis I divided his realm between his four sons, who united to defeat Burgundy in 534. Internecine feuding occurred during the reigns of the brothers Sigebert I and Chilperic I, which was largely fuelled by the rivalry of their queens, Brunhilda and Fredegunda, and which continued during the reigns of their sons and their grandsons. Three distinct subkingdoms emerged: Austrasia, Neustria and Burgundy, each of which developed independently and sought to exert influence over the others. The influence of the Arnulfing clan of Austrasia ensured that the political centre of gravity in the kingdom gradually shifted eastwards to the Rhineland.

The Frankish realm was reunited in 613 by Chlothar II, the son of Chilperic, who granted his nobles the Edict of Paris in an effort to reduce corruption and reassert his authority. Following the military successes of his son and successor Dagobert I, royal authority rapidly declined under a series of kings, traditionally known as les rois fainéants. After the Battle of Tertry in 687, each mayor of the palace, who had formerly been the king's chief household official, effectively held power until in 751, with the approval of the Pope and the nobility, Pepin the Short deposed the last Merovingian king Childeric III and had himself crowned. This inaugurated a new dynasty, the Carolingians.

Carolingian empire (751–843)

Main article: Carolingian Empire

The unification achieved by the Merovingians ensured the continuation of what has become known as the Carolingian Renaissance. The Carolingian Empire was beset by internecine warfare, but the combination of Frankish rule and Roman Christianity ensured that it was fundamentally united. Frankish government and culture depended very much upon each ruler and his aims and so each region of the empire developed differently. Although a ruler's aims depended upon the political alliances of his family, the leading families of Francia shared the same basic beliefs and ideas of government, which had both Roman and Germanic roots.[citation needed]

The Frankish state consolidated its hold over the majority of western Europe by the end of the 8th century, developing into the Carolingian Empire. With the coronation of their ruler Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III in 800 AD, he and his successors were recognised as legitimate successors to the emperors of the Western Roman Empire. As such, the Carolingian Empire gradually came to be seen in the West as a continuation of the ancient Roman Empire. This empire would give rise to several successor states, including France, the Holy Roman Empire and Burgundy, though the Frankish identity remained most closely identified with France.

After the death of Charlemagne, his only adult surviving son became Emperor and King Louis the Pious. Following Louis the Pious's death, however, according to Frankish culture and law that demanded equality among all living male adult heirs, the Frankish Empire was now split between Louis' three sons.

Military

Participation in the Roman army

Germanic peoples, including those tribes in the Rhine delta that later became the Franks, are known to have served in the Roman army since the days of Julius Caesar. After the Roman administration collapsed in Gaul in the 260s, the armies under the Germanic Batavian Postumus revolted and proclaimed him emperor and then restored order. From then on, Germanic soldiers in the Roman army, most notably Franks, were promoted from the ranks. A few decades later, the Menapian Carausius created a Batavian–British rump state on Roman soil that was supported by Frankish soldiers and raiders. Frankish soldiers such as Magnentius, Silvanus and Arbitio held command positions in the Roman army during the mid 4th century. From the narrative of Ammianus Marcellinus it is evident that both Frankish and Alamannic tribal armies were organised along Roman lines.

After the invasion of Chlodio, the Roman armies at the Rhine border became a Frankish "franchise" and Franks were known to levy Roman-like troops that were supported by a Roman-like armour and weapons industry. This lasted at least until the days of the scholar Procopius (c. 500 – c. 565), more than a century after the demise of the Western Roman Empire, who wrote describing the former Arborychoi, having merged with the Franks, retaining their legionary organization in the style of their forefathers during Roman times. The Franks under the Merovingians melded Germanic custom with Romanised organisation and several important tactical innovations. Before their conquest of Gaul, the Franks fought primarily as a tribe, unless they were part of a Roman military unit fighting in conjunction with other imperial units.

Military practices of the early Franks

The primary sources for Frankish military custom and armament are Ammianus Marcellinus, Agathias and Procopius, the latter two Eastern Roman historians writing about Frankish intervention in the Gothic War.

Writing of 539, Procopius says:

His contemporary, Agathias, who based his own writings upon the tropes laid down by Procopius, says:At this time the Franks, hearing that both the Goths and Romans had suffered severely by the war ... forgetting for the moment their oaths and treaties ... (for this nation in matters of trust is the most treacherous in the world), they straightway gathered to the number of one hundred thousand under the leadership of Theudebert I and marched into Italy: they had a small body of cavalry about their leader, and these were the only ones armed with spears, while all the rest were foot soldiers having neither bows nor spears, but each man carried a sword and shield and one axe. Now the iron head of this weapon was thick and exceedingly sharp on both sides, while the wooden handle was very short. And they are accustomed always to throw these axes at a signal in the first charge and thus to shatter the shields of the enemy and kill the men.[43]

While the above quotations have been used as a statement of the military practices of the Frankish nation in the 6th century and have even been extrapolated to the entire period preceding Charles Martel's reforms (early mid-8th century), post-Second World War historiography has emphasised the inherited Roman characteristics of the Frankish military from the date of the beginning of the conquest of Gaul. The Byzantine authors present several contradictions and difficulties. Procopius denies the Franks the use of the spear while Agathias makes it one of their primary weapons. They agree that the Franks were primarily infantrymen, threw axes and carried a sword and shield. Both writers also contradict the authority of Gallic authors of the same general time period (Sidonius Apollinaris and Gregory of Tours) and the archaeological evidence. The Lex Ribuaria, the early 7th century legal code of the Rhineland or Ripuarian Franks, specifies the values of various goods when paying a wergild in kind; whereas a spear and shield were worth only two solidi, a sword and scabbard were valued at seven, a helmet at six, and a "metal tunic" at twelve.[45] Scramasaxes and arrowheads are numerous in Frankish graves even though the Byzantine historians do not assign them to the Franks.The military equipment of this people [the Franks] is very simple ... They do not know the use of the coat of mail or greaves and the majority leave the head uncovered, only a few wear the helmet. They have their chests bare and backs naked to the loins, they cover their thighs with either leather or linen. They do not serve on horseback except in very rare cases. Fighting on foot is both habitual and a national custom and they are proficient in this. At the hip they wear a sword and on the left side their shield is attached. They have neither bows nor slings, no missile weapons except the double edged axe and the angon which they use most often. The angons are spears which are neither very short nor very long. They can be used, if necessary, for throwing like a javelin, and also in hand to hand combat.[44]

The frontispiece of Gregory's Historia Francorum

The evidence of Gregory and of the Lex Salica implies that the early Franks were a cavalry people. In fact, some modern historians have hypothesised that the Franks possessed so numerous a body of horses that they could use them to plough fields and thus were agriculturally technologically advanced over their neighbours. The Lex Ribuaria specifies that a mare's value was the same as that of an ox or of a shield and spear, two solidi and a stallion seven or the same as a sword and scabbard,[45] which suggests that horses were relatively common. Perhaps the Byzantine writers considered the Frankish horse to be insignificant relative to the Greek cavalry, which is probably accurate.[46]

Merovingian military

Composition and development

The Frankish military establishment incorporated many of the pre-existing Roman institutions in Gaul, especially during and after the conquests of Clovis I in the late 5th and early 6th centuries. Frankish military strategy revolved around the holding and taking of fortified centres (castra) and in general these centres were held by garrisons of milities or laeti, who were former Roman mercenaries of Germanic origin. Throughout Gaul, the descendants of Roman soldiers continued to wear their uniforms and perform their ceremonial duties.

Immediately beneath the Frankish king in the military hierarchy were the leudes, his sworn followers, who were generally 'old soldiers' in service away from court.[47] The king had an elite bodyguard called the truste. Members of the truste often served in centannae, garrison settlements that were established for military and police purposes. The day-to-day bodyguard of the king was made up of antrustiones (senior soldiers who were aristocrats in military service) and pueri (junior soldiers and not aristocrats).[48] All high-ranking men had pueri.

The Frankish military was not composed solely of Franks and Gallo-Romans, but also contained Saxons, Alans, Taifals and Alemanni. After the conquest of Burgundy (534), the well-organised military institutions of that kingdom were integrated into the Frankish realm. Chief among these was the standing army under the command of the Patrician of Burgundy.

In the late 6th century, during the wars instigated by Fredegund and Brunhilda, the Merovingian monarchs introduced a new element into their militaries: the local levy. A levy consisted of all the able-bodied men of a district who were required to report for military service when called upon, similar to conscription. The local levy applied only to a city and its environs. Initially only in certain cities in western Gaul, in Neustria and Aquitaine, did the kings possess the right or power to call up the levy. The commanders of the local levies were always different from the commanders of the urban garrisons. Often the former were commanded by the counts of the districts. A much rarer occurrence was the general levy, which applied to the entire kingdom and included peasants (pauperes and inferiores). General levies could also be made within the still-pagan trans-Rhenish stem duchies on the orders of a monarch. The Saxons, Alemanni and Thuringii all had the institution of the levy and the Frankish monarchs could depend upon their levies until the mid-7th century, when the stem dukes began to sever their ties to the monarchy. Radulf of Thuringia called up the levy for a war against Sigebert III in 640.

Soon the local levy spread to Austrasia and the less Romanised regions of Gaul. On an intermediate level, the kings began calling up territorial levies from the regions of Austrasia (which did not have major cities of Roman origin). All the forms of the levy gradually disappeared, however, in the course of the 7th century after the reign of Dagobert I. Under the so-called rois fainéants, the levies disappeared by mid-century in Austrasia and later in Burgundy and Neustria. Only in Aquitaine, which was fast becoming independent of the central Frankish monarchy, did complex military institutions persist into the 8th century. In the final half of the 7th century and first half of the 8th in Merovingian Gaul, the chief military actors became the lay and ecclesiastical magnates with their bands of armed followers called retainers. The other aspects of the Merovingian military, mostly Roman in origin or innovations of powerful kings, disappeared from the scene by the 8th century.

Strategy, tactics and equipment

Merovingian armies used coats of mail, helmets, shields, lances, swords, bows and arrows and war horses. The armament of private armies resembled those of the Gallo-Roman potentiatores of the late Empire. A strong element of Alanic cavalry settled in Armorica influenced the fighting style of the Bretons down into the 12th century. Local urban levies could be reasonably well-armed and even mounted, but the more general levies were composed of pauperes and inferiores, who were mostly farmers by trade and carried ineffective weapons, such as farming implements. The peoples east of the Rhine – Franks, Saxons and even Wends – who were sometimes called upon to serve, wore rudimentary armour and carried weapons such as spears and axes. Few of these men were mounted.[citation needed]