Charlemagne

Charlemagne (English:

/ˈʃɑːrləmeɪn, ˌʃɑːrləˈmeɪn/; French:

[ʃaʁləmaɲ])

[3] or Charles the Great

[a]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlemagne#cite_note-5 (2 April 748

[4][c] – 28 January 814), numbered Charles I, was the

King of the Franks from 768, the

King of the Lombards from 774, and the

Emperor of the Romans from 800. During the

Early Middle Ages, he united the majority of

western and

central Europe. He was the first recognised emperor to rule from western Europe since the

fall of the Western Roman Empire around three centuries earlier.

[5] The expanded

Frankish state that Charlemagne founded is called the

Carolingian Empire. He was later canonised by

Antipope Paschal III.

Charlemagne was the eldest son of

Pepin the Short and

Bertrada of Laon, born before their canonical marriage.

[6] He became king of the Franks in 768 following his father's death, initially as co-ruler with his brother

Carloman I, until the latter’s death in 771.

[7] As sole ruler, he continued his father's policy towards the papacy and became its protector, removing the

Lombards from power in northern

Italy and leading an incursion into

Muslim Spain. He campaigned against the

Saxons to his east,

Christianising them upon penalty of death and leading to events such as the

Massacre of Verden. He reached the height of his power in 800 when he was

crowned "Emperor of the Romans" by

Pope Leo III on

Christmas Day at

Old St. Peter's Basilica in

Rome.

Charlemagne has been called the "Father of Europe" (

Pater Europae),

[8] as he united most of Western Europe for the first time since the

classical era of the

Roman Empire and united parts of Europe that had never been under Frankish or Roman rule. His rule spurred the

Carolingian Renaissance, a period of energetic cultural and intellectual activity within the

Western Church. The

Eastern Orthodox Church viewed Charlemagne less favourably due to his support of the

filioque and the Pope's having preferred him as emperor over the

Byzantine Empire's first female monarch,

Irene of Athens. These and other disputes led to the eventual later split of

Rome and

Constantinople in the

Great Schism of 1054.

[9][d]

Charlemagne died in 814 and was laid to rest in

Aachen Cathedral in his imperial capital city of

Aachen. He married at least four times and had three legitimate sons who lived to adulthood, but only the youngest of them,

Louis the Pious, survived to succeed him. He also had numerous illegitimate children with his

concubines.

Name

Reliquary with idealized

bust of Charlemagne, located at

Aachen Cathedral Treasury

Arm reliquary of Charlemagne at Aachen Cathedral Treasury

He was named

Charles in French and English,

Carolus in Latin, after his grandfather,

Charles Martel. Later Old French historians dubbed him

Charles le Magne (Charles the Great),

[10] becoming Charlemagne in English after the

Norman conquest of England. The epithet Carolus Magnus was widely used, leading to numerous translations into many languages of Europe.

Charles' achievements gave a new meaning to

his name. In many

languages of Europe, the very word for "king" derives from his name; e.g.,

Polish:

król,

Ukrainian: король (korol'),

Czech:

král,

Slovak:

kráľ,

Hungarian:

király,

Lithuanian:

karalius,

Latvian:

karalis,

Russian: король,

Macedonian: крал,

Bulgarian: крал,

Romanian:

crai,

Serbo-Croatian:

краљ/kralj,

Turkish:

kral. This development parallels that of the name of the

Caesars in the original Roman Empire, which became

kaiser and

tsar (or

czar), among others.

[11]

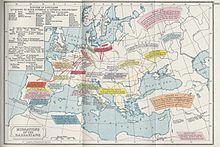

Political background

Francia, early 8th century

By the 6th century, the western

Germanic tribe of the

Franks had been

Christianised, due in considerable measure to the Catholic conversion of

Clovis I.

[12] Francia, ruled by the

Merovingians, was the most powerful of the kingdoms that succeeded the

Western Roman Empire.

[13] Following the

Battle of Tertry, the Merovingians declined into powerlessness, for which they have been dubbed the

rois fainéants ("do-nothing kings").

[14] Almost all government powers were exercised by their chief officer, the

mayor of the palace.

[e]

In 687,

Pepin of Herstal, mayor of the palace of

Austrasia, ended the strife between various kings and their mayors with his victory at Tertry.

[15] He became the sole governor of the entire Frankish kingdom. Pepin was the grandson of two important figures of the Austrasian Kingdom: Saint

Arnulf of Metz and

Pepin of Landen.

[16] Pepin of Herstal was eventually succeeded by his son Charles, later known as

Charles Martel (Charles the Hammer).

[17]

Place of birth

Charlemagne's exact birthplace is unknown, although historians have suggested

Aachen in modern-day Germany, and

Liège (

Herstal) in present-day Belgium as possible locations.

[24] Aachen and Liège are close to the region whence the Merovingian and Carolingian families originated. Other cities have been suggested, including

Düren,

Gauting,

Mürlenbach,

[25] Quierzy, and

Prüm. No definitive evidence resolves the question.

Ancestry

Charlemagne was the eldest child of

Pepin the Short (714 – 24 September 768, reigned from 751) and his wife

Bertrada of Laon (720 – 12 July 783), daughter of

Caribert of Laon. Many historians consider Charlemagne (Charles) to have been illegitimate, although some state that this is arguable,

[26] because Pepin did not marry Bertrada until 744, which was after Charles' birth; this status did not exclude him from the succession.

[27][28][29]

Records name only

Carloman,

Gisela, and three short-lived children named Pepin, Chrothais and Adelais as his younger siblings.

It would be folly, I think, to write a word concerning Charles' birth and infancy, or even his boyhood, for nothing has ever been written on the subject, and there is no one alive now who can give information on it.

—

Einhard[30]

Ambiguous high office

Further information:

Mayor of the Palace

The most powerful officers of the Frankish people, the Mayor of the Palace (

Maior Domus) and one or more kings (

rex,

reges), were appointed by the election of the people. Elections were not periodic, but were held as required to elect officers

ad quos summa imperii pertinebat, "to whom the highest matters of state pertained". Evidently, interim decisions could be made by the Pope, which ultimately needed to be ratified using an assembly of the people that met annually.

[31]

Before he was elected king in 751, Pepin was initially a mayor, a high office he held "as though hereditary" (

velut hereditario fungebatur). Einhard explains that "the honour" was usually "given by the people" to the distinguished, but Pepin the Great and his brother Carloman the Wise received it as though hereditary, as had their father,

Charles Martel. There was, however, a certain ambiguity about quasi-inheritance. The office was treated as joint property: one Mayorship held by two brothers jointly.

[32] Each, however, had his own geographic jurisdiction. When Carloman decided to resign, becoming ultimately a Benedictine at

Monte Cassino,

[33] the question of the disposition of his quasi-share was settled by the pope. He converted the mayorship into a kingship and awarded the joint property to Pepin, who gained the right to pass it on by inheritance.

[34]

This decision was not accepted by all family members. Carloman had consented to the temporary tenancy of his own share, which he intended to pass on to his son, Drogo, when the inheritance should be settled at someone's death. By the Pope's decision, in which Pepin had a hand, Drogo was to be disqualified as an heir in favour of his cousin Charles. He took up arms in opposition to the decision and was joined by

Grifo, a half-brother of Pepin and Carloman, who had been given a share by Charles Martel, but was stripped of it and held under loose arrest by his half-brothers after an attempt to seize their shares by military action. Grifo perished in combat in the Battle of

Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne while Drogo was hunted down and taken into custody.

[35]

On the death of Pepin, 24 September 768, the kingship passed jointly to his sons, "with divine assent" (

divino nutu).

[36] According to the

Life, Pepin died in Paris. The Franks "in general assembly" (

generali conventu) gave them both the rank of a king (

reges) but "partitioned the whole body of the kingdom equally" (

totum regni corpus ex aequo partirentur). The

annals[37] tell a slightly different version, with the king dying at

St-Denis, near Paris. The two "lords" (

domni) were "elevated to kingship" (

elevati sunt in regnum), Charles on 9 October in

Noyon, Carloman on an unspecified date in

Soissons. If born in 742, Charles was 26 years old, but he had been campaigning at his father's right hand for several years, which may help to account for his military skill.

Carloman was 17.

The language, in either case, suggests that there were not two inheritances, which would have created distinct kings ruling over distinct kingdoms, but a single joint inheritance and a joint kingship tenanted by two equal kings, Charles and his brother Carloman. As before, distinct jurisdictions were awarded. Charles received Pepin's original share as Mayor: the outer parts of the kingdom bordering on the sea, namely

Neustria, western

Aquitaine, and the northern parts of

Austrasia; while Carloman was awarded his uncle's former share, the inner parts: southern Austrasia,

Septimania, eastern Aquitaine,

Burgundy, Provence, and

Swabia, lands bordering

Italy. The question of whether these jurisdictions were joint shares reverting to the other brother if one brother died or were inherited property passed on to the descendants of the brother who died was never definitely settled. It came up repeatedly over the succeeding decades until the grandsons of Charlemagne created distinct sovereign kingdoms.

Aquitainian rebellion

Formation of a new Aquitaine

Main article:

Aquitaine

In southern

Gaul,

Aquitaine had been Romanised and people spoke a

Romance language. Similarly,

Hispania had been populated by peoples who spoke various languages, including

Celtic, but these had now been mostly replaced by Romance languages. Between Aquitaine and Hispania were the

Euskaldunak, Latinised to

Vascones, or

Basques,

[38] whose country, Vasconia, extended, according to the distributions of place names attributable to the Basques, mainly in the western

Pyrenees but also as far south as the upper

Ebro River in Spain and as far north as the

Garonne River in France.

[39] The French name

Gascony derives from

Vasconia. The Romans were never able to subjugate the whole of Vasconia. The soldiers they recruited for the Roman legions from those parts they did submit and where they founded the region's first cities were valued for their fighting abilities. The border with Aquitaine was at

Toulouse.

In about 660, the

Duchy of Vasconia united with the

Duchy of Aquitaine to form a single realm under

Felix of Aquitaine, ruling from Toulouse. This was a joint kingship with a Basque Duke,

Lupus I.

Lupus is the Latin translation of Basque Otsoa, "wolf".

[40] At Felix's death in 670 the joint property of the kingship reverted entirely to Lupus. As the Basques had no law of joint inheritance but relied on

primogeniture,

Lupus in effect founded a hereditary dynasty of Basque rulers of an expanded Aquitaine.

[41]

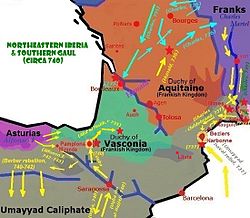

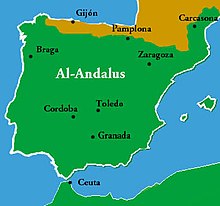

Acquisition of Aquitaine by the Carolingians

Further information:

Umayyad conquest of Hispania

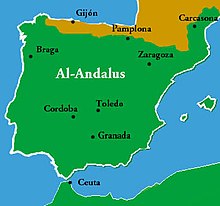

Moorish Hispania

Moorish Hispania in 732

The Latin chronicles of the end of

Visigothic Hispania omit many details, such as identification of characters, filling in the gaps and reconciliation of numerous contradictions.

[42] Muslim sources, however, present a more coherent view, such as in the

Ta'rikh iftitah al-Andalus ("History of the Conquest of al-Andalus") by

Ibn al-Qūṭiyya ("the son of the Gothic woman", referring to the granddaughter of

Wittiza, the last Visigothic king of a united Hispania, who married a Moor). Ibn al-Qūṭiyya, who had another, much longer name, must have been relying to some degree on family oral tradition.

According to Ibn al-Qūṭiyya

[43] Wittiza, the last Visigothic king of a united Hispania died before his three sons, Almund, Romulo, and Ardabast reached maturity. Their mother was

queen regent at

Toledo, but

Roderic, army chief of staff, staged a rebellion, capturing

Córdoba. He chose to impose a joint rule over distinct jurisdictions on the true heirs. Evidence of a division of some sort can be found in the distribution of coins imprinted with the name of each king and in the king lists.

[44] Wittiza was succeeded by Roderic, who reigned for seven and a half years, followed by Achila (Aquila), who reigned three and a half years. If the reigns of both terminated with the incursion of the

Saracens, then Roderic appears to have reigned a few years before the majority of Achila. The latter's kingdom is securely placed to the northeast, while Roderic seems to have taken the rest, notably modern

Portugal.

The Saracens crossed the mountains to claim Ardo's

Septimania, only to encounter the Basque dynasty of Aquitaine, always the allies of the Goths.

Odo the Great of

Aquitaine was at first victorious at the

Battle of Toulouse in 721.

[45] Saracen troops gradually massed in Septimania and in 732 an army under Emir

Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi advanced into Vasconia, and Odo was defeated at the

Battle of the River Garonne. They took

Bordeaux and were advancing towards

Tours when Odo, powerless to stop them, appealed to his arch-enemy,

Charles Martel, mayor of the Franks. In one of the first of the lightning marches for which the Carolingian kings became famous, Charles and his army appeared in the path of the Saracens between Tours and

Poitiers, and in the

Battle of Tours decisively defeated and killed al-Ghafiqi. The Moors returned twice more, each time suffering defeat at Charles' hands—at the River Berre near Narbonne in 737

[46] and in the

Dauphiné in 740.

[47] Odo's price for salvation from the Saracens was incorporation into the Frankish kingdom, a decision that was repugnant to him and also to his heirs.

Loss and recovery of Aquitaine

After the death of his father,

Hunald I allied himself with free

Lombardy. However, Odo had ambiguously left the kingdom jointly to his two sons, Hunald and Hatto. The latter, loyal to Francia, now went to war with his brother over full possession. Victorious, Hunald blinded and imprisoned his brother, only to be so stricken by conscience that he resigned and entered the church as a monk to do penance. The story is told in

Annales Mettenses priores.

[48] His son

Waifer took an early inheritance, becoming duke of Aquitaine and ratified the alliance with Lombardy. Waifer decided to honour it, repeating his father's decision, which he justified by arguing that any agreements with Charles Martel became invalid on Martel's death. Since

Aquitaine was now Pepin's inheritance because of the earlier assistance that was given by Charles Martel, according to some the latter and his son, the young Charles, hunted down Waifer, who could only conduct a guerrilla war, and executed him.

[49]

Among the contingents of the Frankish army were

Bavarians under

Tassilo III, Duke of Bavaria, an

Agilofing, the hereditary Bavarian ducal family.

Grifo had installed himself as Duke of Bavaria, but Pepin replaced him with a member of the ducal family yet a child, Tassilo, whose protector he had become after the death of his father. The loyalty of the Agilolfings was perpetually in question, but Pepin exacted numerous oaths of loyalty from Tassilo. However, the latter had married

Liutperga, a daughter of

Desiderius, king of

Lombardy. At a critical point in the campaign, Tassilo left the field with all his Bavarians. Out of reach of Pepin, he repudiated all loyalty to Francia.

[50] Pepin had no chance to respond as he grew ill and died within a few weeks after Waifer's execution.

The first event of the brothers' reign was the uprising of the Aquitainians and

Gascons, in 769, in that territory split between the two kings. One year earlier, Pepin had finally defeated

Waifer,

Duke of Aquitaine, after waging a destructive, ten-year war against Aquitaine. Now,

Hunald II led the Aquitainians as far north as

Angoulême. Charles met Carloman, but Carloman refused to participate and returned to Burgundy. Charles went to war, leading an army to

Bordeaux, where he set up a fort at Fronsac. Hunald was forced to flee to the court of Duke

Lupus II of Gascony. Lupus, fearing Charles, turned Hunald over in exchange for peace, and Hunald was put in a monastery. Gascon lords also surrendered, and Aquitaine and

Gascony were finally fully subdued by the Franks.

Marriage to Desiderata

The brothers maintained lukewarm relations with the assistance of their mother Bertrada, but in 770 Charles signed a treaty with Duke

Tassilo III of Bavaria and married a Lombard Princess (commonly known today as

Desiderata), the daughter of King Desiderius, to surround Carloman with his own allies. Though

Pope Stephen III first opposed the marriage with the Lombard princess, he found little to fear from a Frankish-Lombard alliance.

Less than a year after his marriage, Charlemagne repudiated Desiderata and married a 13-year-old Swabian named

Hildegard. The repudiated Desiderata returned to her father's court at

Pavia. Her father's wrath was now aroused, and he would have gladly allied with Carloman to defeat Charles. Before any open hostilities could be declared, however, Carloman died on 5 December 771, apparently of natural causes. Carloman's widow

Gerberga fled to Desiderius' court with her sons for protection.

Wives, concubines, and children

Charlemagne had eighteen children with eight of his ten known wives or concubines.

[51][52] Nonetheless, he had only four legitimate grandsons, the four sons of his fourth son, Louis. In addition, he had a grandson (

Bernard of Italy, the only son of his third son,

Pepin of Italy), who was illegitimate but included in the line of inheritance. Among his descendants are several royal dynasties, including the

Habsburg, and

Capetian dynasties. By consequence, most if not all established European noble families ever since can genealogically trace some of their background to Charlemagne.

| Start date | Wives and their children | Concubines and their children |

|---|

| c.768 | His first relationship was with Himiltrude. The nature of this relationship is variously described as concubinage, a legal marriage, or a Friedelehe.[f](Charlemagne put her aside when he married Desiderata.) The union with Himiltrude produced a son:

| |

| c. 770 | After her, his first wife was Desiderata, daughter of Desiderius, king of the Lombards; married in 770, annulled in 771. | |

| c. 771 | His second wife was Hildegard of the Vinzgau(757 or 758–783), married 771, died 783. By her he had nine children:

- Charles the Younger (c. 772–4 December 811), Duke of Maine, and crowned King of the Franks on 25 December 800

- Carloman, renamed Pepin (April 773–8 July 810), King of Italy

- Adalhaid (774), who was born whilst her parents were on campaign in Italy. She was sent back to Francia, but died before reaching Lyons

- Rotrude (or Hruodrud) (775–6 June 810)

- Louis (778–20 June 840), twin of Lothair, King of Aquitaine since 781, crowned King of the Franks/co-emperor in 813, senior Emperor from 814

- Lothair (778–6 February 779/780), twin of Louis, he died in infancy[53]

- Bertha (779–826)

- Gisela (781–808)

- Hildegarde (782–783)

| |

| c. 773 | | His first known concubine was Gersuinda. By her he had:

|

| c. 774 | | His second known concubine was Madelgard. By her he had:

|

| c. 784 | His third wife was Fastrada, married 784, died 794. By her he had:

| |

| c. 794 | His fourth wife was Luitgard, married 794, died childless. | |

| c. 800 | | His fourth known concubine was Regina. By her he had:

|

| c. 804 | | His fifth known concubine was Ethelind. By her he had:

|

Further information:

Carolingian dynasty

Children

During the first peace of any substantial length (780–782), Charles began to appoint his sons to positions of authority. In 781, during a visit to Rome, he made his two youngest sons kings, crowned by the Pope.

[g][h] The elder of these two,

Carloman, was made the

king of Italy, taking the Iron Crown that his father had first worn in 774, and in the same ceremony was renamed "Pepin"

[34][56] (not to be confused with Charlemagne's eldest, possibly illegitimate son,

Pepin the Hunchback). The younger of the two,

Louis, became

King of Aquitaine. Charlemagne ordered Pepin and Louis to be raised in the customs of their kingdoms, and he gave their regents some control of their subkingdoms, but kept the real power, though he intended his sons to inherit their realms. He did not tolerate insubordination in his sons: in 792, he banished Pepin the Hunchback to

Prüm Abbey because the young man had joined a rebellion against him.

Charles was determined to have his children educated, including his daughters, as his parents had instilled the importance of learning in him at an early age.

[57] His children were also taught skills in accord with their aristocratic status, which included training in riding and weaponry for his sons, and embroidery, spinning and weaving for his daughters.

[58]

The sons fought many wars on behalf of their father.

Charles was mostly preoccupied with the Bretons, whose border he shared and who insurrected on at least two occasions and were easily put down. He also fought the Saxons on multiple occasions. In 805 and 806, he was sent into the Böhmerwald (modern

Bohemia) to deal with the Slavs living there (Bohemian tribes, ancestors of the modern

Czechs). He subjected them to Frankish authority and devastated the valley of the Elbe, forcing tribute from them. Pippin had to hold the

Avar and Beneventan borders and fought the

Slavs to his north. He was uniquely poised to fight the

Byzantine Empire when that conflict arose after Charlemagne's imperial coronation and a

Venetian rebellion. Finally, Louis was in charge of the

Spanish March and fought the Duke of Benevento in southern Italy on at least one occasion. He took

Barcelona in a great siege in 797.

Charlemagne kept his daughters at home with him and refused to allow them to contract

sacramental marriages (though he originally condoned an engagement between his eldest daughter Rotrude and

Constantine VI of Byzantium, this engagement was annulled when Rotrude was 11).

[59] Charlemagne's opposition to his daughters' marriages may possibly have intended to prevent the creation of

cadet branches of the family to challenge the main line, as had been the case with

Tassilo of Bavaria. However, he tolerated their extramarital relationships, even rewarding their common-law husbands and treasuring the illegitimate grandchildren they produced for him. He also refused to believe stories of their wild behaviour. After his death the surviving daughters were banished from the court by their brother, the pious Louis, to take up residence in the convents they had been bequeathed by their father. At least one of them, Bertha, had a recognised relationship, if not a marriage, with

Angilbert, a member of Charlemagne's court circle.

[60][61]

Italian campaigns

Conquest of the Lombard kingdom

The Frankish king Charlemagne was a devout Catholic and maintained a close relationship with the papacy throughout his life. In 772, when

Pope Adrian I was threatened by invaders, the king rushed to Rome to provide assistance. Shown here, the pope asks Charlemagne for help at a meeting near Rome.

At his succession in 772,

Pope Adrian I demanded the return of certain cities in the former

exarchate of Ravenna in accordance with a promise at the succession of Desiderius. Instead, Desiderius took over certain papal cities and invaded the

Pentapolis, heading for Rome. Adrian sent ambassadors to Charlemagne in autumn requesting he enforce the policies of his father, Pepin. Desiderius sent his own ambassadors denying the pope's charges. The ambassadors met at

Thionville, and Charlemagne upheld the pope's side. Charlemagne demanded what the pope had requested, but Desiderius swore never to comply. Charlemagne and his uncle

Bernard crossed the Alps in 773 and chased the Lombards back to

Pavia, which they then besieged.

[62] Charlemagne temporarily left the siege to deal with

Adelchis, son of Desiderius, who was raising an army at

Verona. The young prince was chased to the

Adriatic littoral and fled to

Constantinople to plead for assistance from

Constantine V, who was waging war with

Bulgaria.

[34][63]

The siege lasted until the spring of 774 when Charlemagne visited the pope in Rome. There he confirmed

his father's grants of land,

[56] with some later chronicles falsely claiming that he also expanded them, granting

Tuscany,

Emilia, Venice and

Corsica. The pope granted him the title

patrician. He then returned to Pavia, where the Lombards were on the verge of surrendering. In return for their lives, the Lombards surrendered and opened the gates in early summer. Desiderius was sent to the

abbey of

Corbie, and his son Adelchis died in

Constantinople, a patrician. Charles, unusually, had himself crowned with the

Iron Crown and made the magnates of Lombardy pay homage to him at Pavia. Only Duke

Arechis II of Benevento refused to submit and proclaimed independence. Charlemagne was then master of Italy as king of the Lombards. He left Italy with a garrison in Pavia and a few Frankish counts in place the same year.

Instability continued in Italy. In 776, Dukes

Hrodgaud of Friuli and

Hildeprand of Spoleto rebelled. Charlemagne rushed back from

Saxony and defeated the Duke of Friuli in battle; the Duke was slain.

[34] The Duke of Spoleto signed a treaty. Their co-conspirator, Arechis, was not subdued, and Adelchis, their candidate in

Byzantium, never left that city. Northern Italy was now faithfully his.

Southern Italy

In 787, Charlemagne directed his attention towards the

Duchy of Benevento,

[64] where

Arechis II was reigning independently with the self-given title of

Princeps. Charlemagne's siege of

Salerno forced Arechis into submission. However, after Arechis II's death in 787, his son

Grimoald III proclaimed the Duchy of Benevento newly independent. Grimoald was attacked many times by Charles' or his sons' armies, without achieving a definitive victory.

[65] Charlemagne lost interest and never again returned to

Southern Italy where Grimoald was able to keep the Duchy free from Frankish

suzerainty.

Carolingian expansion to the south

Vasconia and the Pyrenees

Europe in 771

The destructive war led by Pepin in Aquitaine, although brought to a satisfactory conclusion for the Franks, proved the Frankish power structure south of the

Loire was feeble and unreliable. After the defeat and death of

Waiofar in 768, while Aquitaine submitted again to the Carolingian dynasty, a new rebellion broke out in 769 led by Hunald II, a possible son of Waifer. He took refuge with the ally Duke

Lupus II of Gascony, but probably out of fear of Charlemagne's reprisal, Lupus handed him over to the new King of the Franks to whom he pledged loyalty, which seemed to confirm the peace in

the Basque area south of the

Garonne.

[66] In the campaign of 769, Charlemagne seems to have followed a policy of "overwhelming force" and avoided a major pitched battle

[67]

Wary of new Basque uprisings, Charlemagne seems to have tried to contain Duke Lupus's power by appointing

Seguin as the Count of Bordeaux (778) and other counts of Frankish background in bordering areas (

Toulouse,

County of Fézensac). The

Basque Duke, in turn, seems to have contributed decisively or schemed the

Battle of Roncevaux Pass (referred to as "Basque treachery"). The defeat of Charlemagne's army in Roncevaux (778) confirmed his determination to rule directly by establishing the Kingdom of Aquitaine (ruled by

Louis the Pious) based on a power base of Frankish officials, distributing lands among colonisers and allocating lands to the Church, which he took as an ally. A Christianisation programme was put in place across the high

Pyrenees (778).

[66]

The new political arrangement for Vasconia did not sit well with local lords. As of 788

Adalric was fighting and capturing

Chorson, Carolingian Count of Toulouse. He was eventually released, but Charlemagne, enraged at the compromise, decided to depose him and appointed his trustee

William of Gellone. William, in turn, fought the Basques and defeated them after banishing Adalric (790).

[66]

From 781 (

Pallars,

Ribagorça) to 806 (

Pamplona under Frankish influence), taking the County of Toulouse for a power base, Charlemagne asserted Frankish authority over the Pyrenees by subduing the south-western marches of Toulouse (790) and establishing vassal counties on the southern Pyrenees that were to make up the

Marca Hispanica.

[68] As of 794, a Frankish vassal, the Basque lord Belasko (

al-Galashki, 'the Gaul') ruled

Álava, but Pamplona remained under Cordovan and local control up to 806. Belasko and the counties in the Marca Hispánica provided the necessary base to attack the

Andalusians (an expedition led by

William Count of Toulouse and Louis the Pious to capture Barcelona in 801). Events in the Duchy of Vasconia (rebellion in Pamplona,

count overthrown in Aragon, Duke Seguin of Bordeaux deposed, uprising of the Basque lords, etc.) were to prove it ephemeral upon Charlemagne's death.

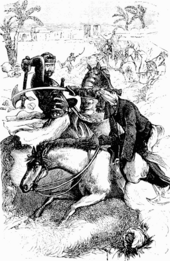

Roncesvalles campaign

See also:

Abbasid–Carolingian alliance

According to the Muslim historian

Ibn al-Athir, the

Diet of

Paderborn had received the representatives of the Muslim rulers of

Zaragoza,

Girona,

Barcelona and

Huesca. Their masters had been cornered in the

Iberian peninsula by

Abd ar-Rahman I, the

Umayyad emir of Cordova. These "Saracen" (

Moorish and

Muladi) rulers offered their homage to the king of the Franks in return for military support. Seeing an opportunity to extend

Christendom and his own power and believing the Saxons to be a fully conquered nation, Charlemagne agreed to go to Spain.

In 778, he led the Neustrian army across the Western

Pyrenees, while the Austrasians, Lombards, and Burgundians passed over the Eastern Pyrenees. The armies met at Saragossa and Charlemagne received the homage of the Muslim rulers, Sulayman al-Arabi and Kasmin ibn Yusuf, but the city did not fall for him. Indeed, Charlemagne faced the toughest battle of his career. The Muslims forced him to retreat. He decided to go home since he could not trust the

Basques, whom he had subdued by conquering

Pamplona. He turned to leave Iberia, but as he was passing through the Pass of

Roncesvalles one of the most famous events of his reign occurred. The Basques attacked and destroyed his rearguard and baggage train. The

Battle of Roncevaux Pass, though less a battle than a skirmish, left many famous dead, including the

seneschal Eggihard, the count of the palace Anselm, and the

warden of the

Breton March,

Roland, inspiring the subsequent creation of the

Song of Roland (

La Chanson de Roland).

Contact with the Saracens

Harun al-Rashid

Harun al-Rashid receiving a delegation of Charlemagne in

Baghdad, by

Julius Köckert (1864)

The conquest of Italy brought Charlemagne in contact with the

Saracens who, at the time, controlled the

Mediterranean. Charlemagne's eldest son,

Pepin the Hunchback, was much occupied with Saracens in Italy. Charlemagne conquered

Corsica and

Sardinia at an unknown date and in 799 the

Balearic Islands. The islands were often attacked by Saracen pirates, but the counts of

Genoa and Tuscany (

Boniface) controlled them with large fleets until the end of Charlemagne's reign. Charlemagne even had contact with the

caliphal court in

Baghdad. In 797 (or possibly 801), the caliph of Baghdad,

Harun al-Rashid, presented Charlemagne with an

Asian elephant named

Abul-Abbas and a

clock.

[69]

Wars with the Moors

In

Hispania, the struggle against the Moors continued unabated throughout the latter half of his reign. Louis was in charge of the Spanish border. In 785, his men captured Girona permanently and extended Frankish control into the

Catalan littoral for the duration of Charlemagne's reign (the area remained nominally Frankish until the

Treaty of Corbeil in 1258). The Muslim chiefs in the northeast of

Islamic Spain were constantly rebelling against Cordovan authority, and they often turned to the Franks for help. The Frankish border was slowly extended until 795, when Girona,

Cardona,

Ausona and

Urgell were united into the new

Spanish March, within the old duchy of

Septimania.

In 797,

Barcelona, the greatest city of the region, fell to the Franks when Zeid, its governor, rebelled against Cordova and, failing, handed it to them. The

Umayyad authority recaptured it in 799. However, Louis of Aquitaine marched the entire army of his kingdom over the

Pyrenees and besieged it for two years, wintering there from 800 to 801, when it capitulated. The Franks continued to press forward against the

emir. They took

Tarragona in 809 and

Tortosa in 811. The last conquest brought them to the mouth of the

Ebro and gave them raiding access to

Valencia, prompting the Emir

al-Hakam I to recognise their conquests in 813.

Eastern campaigns

Saxon Wars

Further information:

Saxon Wars

A map showing Charlemagne's additions (in light green) to the

Frankish Kingdom

Charlemagne was engaged in almost constant warfare throughout his reign,

[70] often at the head of his elite

scara bodyguard squadrons. In the

Saxon Wars, spanning thirty years and eighteen battles, he conquered

Saxonia and proceeded to convert it to Christianity.

The

Germanic Saxons were divided into four subgroups in four regions. Nearest to

Austrasia was

Westphalia and furthest away was

Eastphalia. Between them was

Engria and north of these three, at the base of the

Jutland peninsula, was

Nordalbingia.

In his first campaign, in 773, Charlemagne forced the Engrians to submit and cut down an

Irminsul pillar near

Paderborn.

[71] The campaign was cut short by his first expedition to Italy. He returned in 775, marching through Westphalia and conquering the Saxon fort at

Sigiburg. He then crossed Engria, where he defeated the Saxons again. Finally, in Eastphalia, he defeated a Saxon force, and its leader

Hessi converted to Christianity. Charlemagne returned through Westphalia, leaving encampments at Sigiburg and

Eresburg, which had been important Saxon bastions. He then controlled Saxony with the exception of Nordalbingia, but Saxon resistance had not ended.

Following his subjugation of the Dukes of Friuli and Spoleto, Charlemagne returned rapidly to Saxony in 776, where a rebellion had destroyed his fortress at Eresburg. The Saxons were once again defeated, but their main leader,

Widukind, escaped to Denmark, his wife's home. Charlemagne built a new camp at

Karlstadt. In 777, he called a national diet at Paderborn to integrate Saxony fully into the Frankish kingdom. Many Saxons were baptised as Christians.

In the summer of 779, he again invaded Saxony and reconquered Eastphalia, Engria and Westphalia. At a diet near

Lippe, he divided the land into missionary districts and himself assisted in several mass baptisms (780). He then returned to Italy and, for the first time, the Saxons did not immediately revolt. Saxony was peaceful from 780 to 782.

Charlemagne receiving the submission of

Widukind at

Paderborn in 785, painted c. 1840 by

Ary Scheffer

He returned to Saxony in 782 and instituted a code of law and appointed counts, both Saxon and Frank. The laws were draconian on religious issues; for example, the

Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae prescribed death to Saxon pagans who refused to convert to Christianity. This led to renewed conflict. That year, in autumn, Widukind returned and led a new revolt. In response, at

Verden in Lower Saxony, Charlemagne is recorded as having ordered the execution of 4,500 Saxon prisoners by beheading, known as the

Massacre of Verden ("Verdener Blutgericht"). The killings triggered three years of renewed bloody warfare. During this war, the

East Frisians between the

Lauwers and the

Weser joined the Saxons in revolt and were finally subdued.

[72] The war ended with Widukind accepting baptism.

[73] The Frisians afterwards asked for missionaries to be sent to them and a bishop of their own nation,

Ludger, was sent. Charlemagne also promulgated a law code, the

Lex Frisonum, as he did for most subject peoples.

[74]

Thereafter, the Saxons maintained the peace for seven years, but in 792 Westphalia again rebelled. The Eastphalians and Nordalbingians joined them in 793, but the insurrection was unpopular and was put down by 794. An Engrian rebellion followed in 796, but the presence of Charlemagne, Christian Saxons and

Slavs quickly crushed it. The last insurrection occurred in 804, more than thirty years after Charlemagne's first campaign against them, but also failed. According to Einhard:

The war that had lasted so many years was at length ended by their acceding to the terms offered by the King; which were renunciation of their national religious customs and the worship of devils, acceptance of the sacraments of the Christian faith and religion, and union with the Franks to form one people.

Submission of Bavaria

By 774, Charlemagne had invaded the

Kingdom of Lombardy, and he later annexed the Lombardian territories and assumed its crown, placing the

Papal States under Frankish protection.

[75] The

Duchy of Spoleto south of Rome was acquired in 774, while in the central western parts of Europe, the

Duchy of Bavaria was absorbed and the Bavarian policy continued of establishing tributary

marches, (borders protected in return for tribute or taxes) among the

Slavic Serbs and Czechs. The remaining power confronting the Franks in the east were the

Avars. However, Charlemagne acquired other Slavic areas, including

Bohemia,

Moravia,

Austria and

Croatia.

[75]

In 789, Charlemagne turned to

Bavaria. He claimed that

Tassilo III, Duke of Bavaria was an unfit ruler, due to his oath-breaking. The charges were exaggerated, but Tassilo was deposed anyway and put in the monastery of

Jumièges.

[76] In 794, Tassilo was made to renounce any claim to Bavaria for himself and his family (the

Agilolfings) at the

synod of

Frankfurt; he formally handed over to the king all of the rights he had held.

[77] Bavaria was subdivided into Frankish counties, as had been done with Saxony.

Avar campaigns

In 788, the

Avars, an Asian nomadic group that had settled down in what is today

Hungary (Einhard called them

Huns), invaded Friuli and Bavaria. Charlemagne was preoccupied with other matters until 790 when he marched down the

Danube and ravaged Avar territory to the

Győr. A Lombard army under Pippin then marched into the

Drava valley and ravaged

Pannonia. The campaigns ended when the Saxons revolted again in 792.

For the next two years, Charlemagne was occupied, along with the Slavs, against the Saxons. Pippin and Duke

Eric of Friuli continued, however, to assault the Avars' ring-shaped strongholds. The great Ring of the Avars, their capital fortress, was taken twice. The booty was sent to Charlemagne at his capital,

Aachen, and redistributed to his followers and to foreign rulers, including King

Offa of Mercia. Soon the Avar

tuduns had lost the will to fight and travelled to Aachen to become vassals to Charlemagne and to become Christians. Charlemagne accepted their surrender and sent one native chief, baptised Abraham, back to Avaria with the ancient title of

khagan. Abraham kept his people in line, but in 800, the

Bulgarians under

Khan Krum attacked the remains of the Avar state.

In 803, Charlemagne sent a Bavarian army into

Pannonia, defeating and bringing an end to the

Avar confederation.

[78]

In November of the same year, Charlemagne went to Regensburg where the Avar leaders acknowledged him as their ruler.

[78] In 805, the Avar khagan, who had already been baptised, went to Aachen to ask permission to settle with his people south-eastward from

Vienna.

[78] The

Transdanubian territories became integral parts of the Frankish realm, which was abolished by the

Magyars in 899–900.

Northeast Slav expeditions

In 789, in recognition of his new pagan neighbours, the

Slavs, Charlemagne marched an Austrasian-Saxon army across the

Elbe into

Obotrite territory. The Slavs ultimately submitted, led by their leader Witzin. Charlemagne then accepted the surrender of the

Veleti under Dragovit and demanded many hostages. He also demanded permission to send missionaries into this pagan region unmolested. The army marched to the

Baltic before turning around and marching to the Rhine, winning much booty with no harassment. The tributary Slavs became loyal allies. In 795, when the Saxons broke the peace, the Abotrites and Veleti rebelled with their new ruler against the Saxons. Witzin died in battle and Charlemagne avenged him by harrying the Eastphalians on the Elbe. Thrasuco, his successor, led his men to conquest over the Nordalbingians and handed their leaders over to Charlemagne, who honoured him. The Abotrites remained loyal until Charles' death and fought later against the Danes.

Southeast Slav expeditions

Europe around 800

When Charlemagne incorporated much of Central Europe, he brought the Frankish state face to face with the Avars and Slavs in the southeast.

[79] The most southeast Frankish neighbours were

Croats, who settled in

Pannonian Croatia and

Dalmatian Croatia. While fighting the Avars, the Franks had called for their support.

[80] During the 790s, he won a major victory over them in 796.

[81] Pannonian Croat Duke

Vojnomir of Pannonian Croatia aided Charlemagne, and the Franks made themselves overlords over the Croats of northern Dalmatia,

Slavonia and Pannonia.

[81]

The Frankish commander

Eric of Friuli wanted to extend his dominion by conquering the Littoral Croat Duchy. During that time, Dalmatian Croatia was ruled by Duke

Višeslav of Croatia. In the

Battle of Trsat, the forces of Eric fled their positions and were routed by the forces of Višeslav.

[82] Eric was among those killed which was a great blow for the Carolingian Empire.

[79][83][82]

Charlemagne also directed his attention to the

Slavs to the west of the Avar khaganate: the

Carantanians and

Carniolans. These people were subdued by the Lombards and Bavarii and made tributaries, but were never fully incorporated into the Frankish state.

Imperium

Coronation

Imperial Coronation of Charlemagne, by

Friedrich Kaulbach, 1861

In 799,

Pope Leo III had been assaulted by some of the Romans, who tried to put out his eyes and tear out his tongue.

[84] Leo escaped and fled to Charlemagne at

Paderborn.

[85] Charlemagne, advised by scholar

Alcuin, travelled to Rome, in November 800 and held a synod. On 23 December, Leo swore an oath of innocence to Charlemagne. His position having thereby been weakened, the Pope sought to restore his status. Two days later, at

Mass, on Christmas Day (25 December), when Charlemagne knelt at the altar to pray, the Pope

crowned him

Imperator Romanorum ("Emperor of the Romans") in

Saint Peter's Basilica. In so doing, the Pope rejected the legitimacy of

Empress Irene of

Constantinople:

Pope Leo III, crowning Charlemagne from

Chroniques de France ou de Saint Denis, vol. 1; France, second quarter of 14th century.

When

Odoacer compelled the abdication of

Romulus Augustulus, he did not abolish the Western Empire as a separate power, but caused it to be reunited with or sink into the Eastern, so that from that time there was a single undivided Roman Empire ... [Pope Leo III and Charlemagne], like their predecessors, held the Roman Empire to be one and indivisible, and proposed by the coronation of [Charlemagne] not to proclaim a severance of the East and West ... they were not revolting against a reigning sovereign, but legitimately filling up the place of the deposed

Constantine VI ... [Charlemagne] was held to be the legitimate successor, not of Romulus Augustulus, but of Constantine VI ...

[86]

Charlemagne's coronation as Emperor, though intended to represent the continuation of the unbroken line of Emperors from

Augustus to Constantine VI, had the effect of setting up two separate (and often opposing) Empires and two separate claims to imperial authority. It led to war in 802, and for centuries to come, the Emperors of both West and East would make competing claims of sovereignty over the whole.

Einhard says that Charlemagne was ignorant of the Pope's intent and did not want any such coronation:

[H]e at first had such an aversion that he declared that he would not have set foot in the Church the day that they [the imperial titles] were conferred, although it was a great feast-day, if he could have foreseen the design of the Pope.

[87]

A number of modern scholars, however,

[88] suggest that Charlemagne was indeed aware of the coronation; certainly, he cannot have missed the bejewelled crown waiting on the altar when he came to pray – something even contemporary sources support.

[89]

Debate

The throne of Charlemagne and the subsequent German Kings in

Aachen Cathedral

Historians have debated for centuries whether Charlemagne was aware before the coronation of the Pope's intention to crown him Emperor (Charlemagne declared that he would not have entered Saint Peter's had he known, according to chapter twenty-eight of Einhard's

Vita Karoli Magni),

[90] but that debate obscured the more significant question of

why the Pope granted the title and why Charlemagne accepted it.

Collins points out "[t]hat the motivation behind the acceptance of the imperial title was a romantic and antiquarian interest in reviving the Roman Empire is highly unlikely."

[91] For one thing, such romance would not have appealed either to Franks or Roman Catholics at the turn of the ninth century, both of whom viewed the

Classical heritage of the Roman Empire with distrust. The Franks took pride in having "fought against and thrown from their shoulders the heavy yoke of the Romans" and "from the knowledge gained in baptism, clothed in gold and precious stones the bodies of the holy martyrs whom the Romans had killed by fire, by the sword and by wild animals", as

Pepin III described it in a law of 763 or 764.

[92]

Furthermore, the new title—carrying with it the risk that the new emperor would "make drastic changes to the traditional styles and procedures of government" or "concentrate his attentions on Italy or on Mediterranean concerns more generally"—risked alienating the Frankish leadership.

[93]

For both the Pope and Charlemagne, the Roman Empire remained a significant power in European politics at this time. The

Byzantine Empire, based in

Constantinople, continued to hold a substantial portion of Italy, with borders not far south of Rome. Charles' sitting in judgment of the Pope could be seen as usurping the prerogatives of the Emperor in Constantinople:

By whom, however, could he [the Pope] be tried? Who, in other words, was qualified to pass judgement on the Vicar of Christ? In normal circumstances the only conceivable answer to that question would have been the Emperor at Constantinople; but the imperial throne was at this moment occupied by

Irene. That the Empress was notorious for having blinded and murdered her own son was, in the minds of both Leo and Charles, almost immaterial: it was enough that she was a woman. The female sex was known to be incapable of governing, and by the old Salic tradition was debarred from doing so. As far as Western Europe was concerned, the Throne of the Emperors was vacant: Irene's claim to it was merely an additional proof, if any were needed, of the degradation into which the so-called Roman Empire had fallen.

—

John Julius Norwich[94]

Coronation of Charlemagne, drawing by

Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld

For the Pope, then, there was "no living Emperor at that time"

[95] though

Henri Pirenne[96] disputes this saying that the coronation "was not in any sense explained by the fact that at this moment a woman was reigning in Constantinople". Nonetheless, the Pope took the extraordinary step of creating one. The papacy had since 727 been in conflict with Irene's predecessors in Constantinople over a number of issues, chiefly the continued Byzantine adherence to the doctrine of

iconoclasm, the destruction of Christian images; while from 750, the secular power of the Byzantine Empire in central Italy had been nullified.

By bestowing the Imperial crown upon Charlemagne, the Pope arrogated to himself "the right to appoint ... the Emperor of the Romans, ... establishing the imperial crown as his own personal gift but simultaneously granting himself implicit superiority over the Emperor whom he had created." And "because the Byzantines had proved so unsatisfactory from every point of view—political, military and doctrinal—he would select a westerner: the one man who by his wisdom and statesmanship and the vastness of his dominions ... stood out head and shoulders above his contemporaries."

[97]

With Charlemagne's coronation, therefore, "the Roman Empire remained, so far as either of them [Charlemagne and Leo] were concerned, one and indivisible, with Charles as its Emperor", though there can have been "little doubt that the coronation, with all that it implied, would be furiously contested in Constantinople".

[98]

Alcuin writes hopefully in his letters of an

Imperium Christianum ("Christian Empire"), wherein, "just as the inhabitants of the [Roman Empire] had been united by a common Roman citizenship", presumably this new empire would be united by a common Christian faith.

[92] This writes the view of Pirenne when he says "Charles was the Emperor of the

ecclesia as the Pope conceived it, of the Roman Church, regarded as the universal Church".

[99] The

Imperium Christianum was further supported at a number of

synods all across Europe by Paulinus of Aquileia.

[100]

What is known, from the Byzantine chronicler

Theophanes,

[101] is that Charlemagne's reaction to his coronation was to take the initial steps towards securing the Constantinopolitan throne by sending envoys of marriage to Irene, and that Irene reacted somewhat favourably to them.

The Coronation of Charlemagne

The Coronation of Charlemagne, by assistants of

Raphael, c. 1516–1517

It is important to distinguish between the universalist and localist conceptions of the empire, which remain controversial among historians. According to the former, the empire was a universal monarchy, a "commonwealth of the whole world, whose sublime unity transcended every minor distinction"; and the emperor "was entitled to the obedience of

Christendom". According to the latter, the emperor had no ambition for universal dominion; his realm was limited in the same way as that of every other ruler, and when he made more far-reaching claims his object was normally to ward off the attacks either of the Pope or of the Byzantine emperor. According to this view, also, the origin of the empire is to be explained by specific local circumstances rather than by overarching theories.

[102]

According to Ohnsorge, for a long time, it had been the custom of Byzantium to designate the German princes as spiritual "sons" of the Romans. What might have been acceptable in the fifth century had become provoking and insulting to the Franks in the eighth century. Charles came to believe that the Roman emperor, who claimed to head the world hierarchy of states, was, in reality, no greater than Charles himself, a king as other kings, since beginning in 629 he had entitled himself "Basileus" (translated literally as "king"). Ohnsorge finds it significant that the chief wax seal of Charles, which bore only the inscription: "Christe, protege Carolum regem Francorum [Christ, protect Charles, king of the Franks], was used from 772 to 813, even during the imperial period and was not replaced by a special imperial seal; indicating that Charles felt himself to be just the king of the Franks. Finally, Ohnsorge points out that in the spring of 813 at Aachen Charles crowned his only surviving son, Louis, as the emperor without recourse to Rome with only the acclamation of his Franks. The form in which this acclamation was offered was Frankish-Christian rather than Roman. This implies both independence from Rome and a Frankish (non-Roman) understanding of empire.

[103]

Imperial title

Charlemagne used these circumstances to claim that he was the

"renewer of the Roman Empire", which had declined under the

Byzantines. In his official charters, Charles preferred the style

Karolus serenissimus Augustus a Deo coronatus magnus pacificus imperator Romanum gubernans imperium[104] ("Charles, most serene Augustus crowned by God, the great, peaceful emperor ruling the Roman empire") to the more direct

Imperator Romanorum ("Emperor of the Romans").

The title of Emperor remained in the Carolingian family for years to come, but divisions of territory and in-fighting over supremacy of the Frankish state weakened its significance.

[105] The papacy itself never forgot the title nor abandoned the right to bestow it. When the family of Charles ceased to produce worthy heirs, the Pope gladly crowned whichever Italian magnate could best protect him from his local enemies. The empire would remain in continuous existence for over a millennium, as the

Holy Roman Empire, a true imperial successor to Charles.

[106]

Imperial diplomacy

Europe around 814

The

iconoclasm of the Byzantine Isaurian Dynasty was endorsed by the Franks.

[107] The

Second Council of Nicaea reintroduced the veneration of icons under Empress

Irene. The council was not recognised by Charlemagne since no Frankish emissaries had been invited, even though Charlemagne ruled more than three provinces of the classical Roman empire and was considered equal in rank to the Byzantine emperor. And while the Pope supported the reintroduction of the iconic veneration, he politically digressed from Byzantium.

[107] He certainly desired to increase the influence of the papacy, to honour his saviour Charlemagne, and to solve the constitutional issues then most troubling to European jurists in an era when Rome was not in the hands of an emperor. Thus, Charlemagne's assumption of the imperial title was not a usurpation in the eyes of the Franks or Italians. It was, however, seen as such in Byzantium, where it was protested by Irene and her successor

Nikephoros I—neither of whom had any great effect in enforcing their protests.

The East Romans, however, still held several territories in Italy: Venice (what was left of the

Exarchate of Ravenna),

Reggio (in

Calabria),

Otranto (in

Apulia), and

Naples (the

Ducatus Neapolitanus). These regions remained outside of Frankish hands until 804, when the Venetians, torn by infighting, transferred their allegiance to the Iron Crown of Pippin, Charles' son. The

Pax Nicephori ended. Nicephorus ravaged the coasts with a fleet, initiating the only instance of war between the Byzantines and the Franks. The conflict lasted until 810 when the pro-Byzantine party in Venice gave their city back to the Byzantine Emperor, and the two emperors of Europe made peace: Charlemagne received the

Istrian peninsula and in 812 the emperor

Michael I Rangabe recognised his status as Emperor,

[108] although not necessarily as "Emperor of the Romans".

[109]

Danish attacks

After the conquest of Nordalbingia, the Frankish frontier was brought into contact with Scandinavia. The

pagan Danes, "a race almost unknown to his ancestors, but destined to be only too well known to his sons" as

Charles Oman described them, inhabiting the

Jutland peninsula, had heard many stories from Widukind and his allies who had taken refuge with them about the dangers of the Franks and the fury which their Christian king could direct against pagan neighbours.

In 808, the king of the Danes,

Godfred, expanded the vast

Danevirke across the isthmus of

Schleswig. This defence, last employed in the Danish-Prussian War of 1864, was at its beginning a 30 km (19 mi) long earthenwork rampart. The Danevirke protected Danish land and gave Godfred the opportunity to harass

Frisia and

Flanders with pirate raids. He also subdued the Frank-allied Veleti and fought the Abotrites.

Godfred invaded Frisia, joked of visiting Aachen, but was murdered before he could do any more, either by a Frankish assassin or by one of his own men. Godfred was succeeded by his nephew

Hemming, who concluded the

Treaty of Heiligen with Charlemagne in late 811.

Death

See also:

Testament of Charlemagne

A portion of the 814 death

shroud of Charlemagne. It represents a

quadriga and was manufactured in

Constantinople.

Musée de Cluny, Paris.

Europe at the death of the Charlemagne 814.

In 813, Charlemagne called

Louis the Pious, king of

Aquitaine, his only surviving legitimate son, to his court. There Charlemagne crowned his son as co-emperor and sent him back to Aquitaine. He then spent the autumn hunting before returning to Aachen on 1 November. In January, he fell ill with

pleurisy.

[110] In deep depression (mostly because many of his plans were not yet realised), he took to his bed on 21 January and as

Einhard tells it:

He died January twenty-eighth, the seventh day from the time that he took to his bed, at nine o'clock in the morning, after partaking of the

Holy Communion, in the seventy-second year of his age and the forty-seventh of his reign.

Frederick II's

Frederick II's gold and silver casket for Charlemagne, the

Karlsschrein

He was buried that same day, in

Aachen Cathedral, although the cold weather and the nature of his illness made such a hurried burial unnecessary. The earliest surviving

planctus, the

Planctus de obitu Karoli, was composed by a monk of

Bobbio, which he had patronised.

[111] A later story, told by Otho of Lomello, Count of the Palace at Aachen in the time of

Emperor Otto III, would claim that he and Otto had discovered Charlemagne's tomb: Charlemagne, they claimed, was seated upon a throne, wearing a crown and holding a sceptre, his flesh almost entirely incorrupt. In 1165,

Emperor Frederick I re-opened the tomb again and placed the emperor in a sarcophagus beneath the floor of the cathedral.

[112] In 1215

Emperor Frederick II re-interred him in a casket made of gold and silver known as the

Karlsschrein.

Charlemagne's death emotionally affected many of his subjects, particularly those of the literary clique who had surrounded him at

Aachen. An anonymous monk of Bobbio lamented:

[113]

From the lands where the sun rises to western shores, people are crying and wailing ... the Franks, the Romans, all Christians, are stung with mourning and great worry ... the young and old, glorious nobles, all lament the loss of their Caesar ... the world laments the death of Charles ... O Christ, you who govern the heavenly host, grant a peaceful place to Charles in your kingdom. Alas for miserable me.

Louis succeeded him as Charles had intended. He left

a testament allocating his assets in 811 that was not updated prior to his death. He left most of his wealth to the Church, to be used for charity. His empire lasted only another generation in its entirety; its division, according to custom, between Louis's own sons after their father's death laid the foundation for the modern states of Germany and France.

[114]