Norman conquest of southern Italy

The Kingdom of Sicily (in green) in 1154, representing the extent of the Norman conquest in southern Italy over several decades of activity by independent adventurers

The

Norman conquest of southern Italy lasted from 999 to 1139, involving many battles and independent conquerors. In 1130, the territories in

southern Italy united as the

Kingdom of Sicily, which included the island of

Sicily, the southern third of the

Italian Peninsula (except

Benevento, which was briefly held twice), the archipelago of

Malta, and parts of

North Africa.

Itinerant

Norman forces arrived in the

Mezzogiorno as mercenaries in the service of

Lombard and

Byzantine factions, communicating news swiftly back home about opportunities in the

Mediterranean. These groups gathered in several places, establishing

fiefdoms and states of their own, uniting and elevating their status to

de facto independence within fifty years of their arrival.

Unlike the

Norman conquest of England (1066), which took a few years after

one decisive battle, the conquest of southern Italy was the product of decades and a number of battles, few decisive. Many territories were conquered independently, and only later were unified into a single state. Compared to the conquest of England, it was unplanned and disorganised, but equally complete.

Pre-Norman Viking activity in Italy

There is little evidence for Viking activity in Italy as a precursor to the arrival of the Normans in 999, but some raiding is recorded.

Ermentarius of Noirmoutier and the

Annales Bertiniani provide contemporary evidence for Vikings based in Frankia proceeding to Iberia and thence to Italy around 860.

[1]

Some modern scholars have connected this event with a much later account by the infamously unreliable

Dudo of Saint-Quentin, who has a Viking fleet led by one Alstingus land at the Ligurian port of

Luni and sacking the city. The Vikings then move another 60 miles (97 kilometres) down the Tuscan coast to the mouth of the

Arno, sacking

Pisa and then, following the river upstream, also attack the hill-town of

Fiesole above

Florence and win other victories around the Mediterranean (including in Sicily and North Africa).

[2] Building modern speculation on medieval invention, some scholarship has identified the leaders of this expedition as

Björn Ironside and

Hastein. Dudo's account, however, probably adds no historically reliable information to the brief contemporary annals.

[3]

Other contact between Italy and the Viking world occurred via Eastern Scandinavians coming to Italy via the

Austrvegr (the river routes from the Baltic to the Black Sea) and working as

Varangian mercenaries fighting for Byzantium. In particular, three or four eleventh-century Swedish

Runestones mention Italy, memorialising warriors who died in 'Langbarðaland', the Old Norse name for southern Italy (

Langobardia Minor).

[4] Varangians may first have been deployed as mercenaries in Italy against the Arabs as early as 936.

[5]

Arrival of the Normans in Italy, 999–1017

Map of Italy at the arrival of the Normans, who eventually conquered Sicily and all the territory on the mainland south of the

Holy Roman Empire (the bold line), southern regions of the

Papal States and the

Duchy of Spoleto

The earliest reported date of the arrival of Norman knights in southern Italy is 999, although it may be assumed that they had visited before then. In that year, according to some traditional sources of uncertain origin, Norman pilgrims returning from the

Holy Sepulchre in

Jerusalem via Apulia stayed with

Prince Guaimar III in

Salerno. The city and its environs were attacked by

Saracens from Africa demanding payment of an overdue annual tribute. While Guaimar began to collect the tribute, the Normans ridiculed him and his Lombard subjects for cowardice, and they assaulted their besiegers. The Saracens fled, booty was confiscated and a grateful Guaimar asked the Normans to stay. They refused, but promised to bring his rich gifts to their compatriots in Normandy and tell them about possibly lucrative military service in Salerno. Some sources have Guaimar sending emissaries to Normandy to bring back knights, and this account of the arrival of the Normans is sometimes known as the "Salerno (or Salernitan) tradition".

[6][7]

The Salerno tradition was first recorded by

Amatus of Montecassino in his

Ystoire de li Normant between 1071 and 1086.

[7] Much of this information was borrowed from Amatus by

Peter the Deacon for his continuation of the

Chronicon Monasterii Casinensis of

Leo of Ostia, written during the early 12th century. Beginning with the

Annales Ecclesiastici of

Baronius in the 17th century, the Salernitan story became the accepted history.

[8] Although its factual accuracy was questioned periodically during the following centuries, it has been accepted (with some modifications) by most scholars since.

[9]

Another historical account of the arrival of the first Normans in Italy, the "Gargano tradition", appears in primary chronicles without reference to any previous Norman presence.

[6] According to this account Norman pilgrims at the shrine to

Michael the Archangel at

Monte Gargano in 1016 met the Lombard

Melus of Bari, who persuaded them to join him in an attack on the Byzantine government of Apulia.

As with the Salerno tradition, there are two primary sources for the Gargano story: the

Gesta Roberti Wiscardi of

William of Apulia (dated 1088–1110) and the

Chronica monasterii S. Bartholomaei de Carpineto of a monk named Alexander, written about a century later and based on William's work.

[10] Some scholars have combined the Salerno and Gargano tales, and

John Julius Norwich suggested that the meeting between Melus and the Normans had been arranged by Guaimar.

[11] Melus had been in Salerno just before his visit to Monte Gargano.

Another story involves the exile of a group of brothers from the

Drengot family. One of the brothers,

Osmund (according to

Orderic Vitalis) or

Gilbert (according to Amatus and Peter the Deacon), murdered William Repostel (Repostellus) in the presence of

Robert I, Duke of Normandy after Repostel allegedly boasted about dishonouring his murderer's daughter. Threatened with death, the Drengot brother fled with his siblings to

Rome and one of the brothers had an audience with the

pope before joining Melus (Melo) of Bari. Amatus dates the story to after 1027, and does not mention the pope. According to him, Gilbert's brothers were Osmund,

Ranulf,

Asclettin and

Ludolf (Rudolf, according to Peter).

[12] Between 1016 and 1024, in a fragmented political context, the County of

Ariano was founded by the group of Norman knights headed by Gilbert and hired by Melus. The County, which replaced the pre-existing chamberlainship, is considered to be the first political body established by the Normans in the South of Italy.

[13]

Repostel's murder is dated by all the chronicles to the reign of Robert the Magnificent and after 1027, although some scholars believe "Robert" was a scribal error for "Richard" (

Richard II of Normandy, who was duke in 1017).

[14] The earlier date is necessary if the emigration of the first Normans was connected to the Drengots and the murder of William Repostel. In the

Histories of

Ralph Glaber, "Rodulfus" leaves Normandy after displeasing Count Richard (Richard II).

[15] The sources disagree about which brother was the leader on the southern trip. Orderic and

William of Jumièges, in the latter's

Gesta Normannorum Ducum, name Osmund; Glaber names Rudolph, and Leo, Amatus and

Adhemar of Chabannes name Gilbert. According to most southern-Italian sources, the leader of the Norman contingent at the

Battle of Cannae in 1018 was Gilbert.

[16] If Rudolf is identified with the Rudolf of Amatus' history as a Drengot brother, he may have been the leader at Cannae.

[17]

A modern hypothesis concerning the Norman arrival in the Mezzogiorno concerns the chronicles of Glaber, Adhemar and Leo (not Peter's continuation). All three chronicles indicate that Normans (either a group of 40 or a much-larger force of around 250) under "Rodulfus" (Rudolf), fleeing Richard II, came to

Pope Benedict VIII of Rome. The pope sent them to

Salerno (or

Capua) to seek mercenary employment against the Byzantines because of the latter's invasion of papal Beneventan territory.

[18] There, they met the Beneventan

primates (leading men):

Landulf V of Benevento,

Pandulf IV of Capua, (possibly) Guaimar III of Salerno and Melus of Bari. According to Leo's chronicle, "Rudolf" was

Ralph of Tosni.

[12][19] If the first confirmed Norman military actions in the south involved Melus' mercenaries against the Byzantines in May 1017, the Normans probably left Normandy between January and April.

[20]

Lombard revolt, 1009–1022

The imprisonment of Pandulf of Capua, after Emperor Henry II's 1022 campaign

On 9 May 1009, an insurrection erupted in

Bari against the

Catapanate of Italy, the regional Byzantine authority based there. Led by

Melus, a local Lombard, the revolt quickly spread to other cities. Late that year (or early in 1010) the

katepano,

John Curcuas, was killed in battle. In March 1010 his successor,

Basil Mesardonites, disembarked with reinforcements and besieged the rebels in the city. The Byzantine citizens negotiated with Basil and forced the Lombard leaders, Melus and his brother-in-law

Dattus, to flee. Basil entered the city on 11 June 1011, reestablishing Byzantine authority. He did not follow his victory with severe sanctions, only sending Melus' family (including his son,

Argyrus) to

Constantinople. Basil died in 1016, after years of peace in southern Italy.

Leo Tornikios Kontoleon arrived as Basil's successor in May of that year. After Basil's death, Melus revolted again; this time, he used a newly arrived band of Normans sent by Pope Benedict or who met him (with or without Guaimar's aid) at Monte Gargano. Tornikios sent an army, led by

Leo Passianos, against the Lombard-Norman coalition. Passianos and Melus met on the

Fortore at

Arenula; the battle was either indecisive (

William of Apulia) or a victory for Melus (

Leo of Ostia and Amatus). Tornikios then took command, leading his forces into a second encounter near

Civita.

[21] This second battle was a victory for Melus, although

Lupus Protospatharius and the anonymous chronicler of Bari recorded a defeat.

[21] A third battle (a decisive victory for Melus) took place at

Vaccaricia;

[21] the region from the Fortore to

Trani was in his hands, and in September Tornikios was replaced by

Basil Boiannes (who arrived in December). According to Amatus, there were five consecutive Lombard and Norman victories by October 1018.

[21]

At Boioannes' request, a detachment of the elite

Varangian Guard was sent to Italy to fight the Normans. The armies met at the

Ofanto near

Cannae, the site of

Hannibal's victory over the Romans in 216 BC, and the

Battle of Cannae was a decisive Byzantine victory;

[21] Amatus wrote that only ten Normans survived from a contingent of 250.

[21] After the battle, Ranulf Drengot (one of the Norman survivors) was elected leader of their company.

[21] Boioannes protected his gains by building a fortress at the

Apennine pass, guarding the entrance to the

Apulian plain. In 1019

Troia (as the fortress was known) was garrisoned by Boioannes' Norman troops, an indication of Norman willingness to fight on either side. With Norman mercenaries on both sides, they would obtain good terms for the release of their brethren from their captors regardless of outcome.

[21]

Alarmed by the shift in momentum in the south, Pope Benedict (who may have initiated Norman involvement in the war) went north in 1020 to

Bamberg to confer with

Holy Roman Emperor Henry II. Although the emperor took no immediate action, events the following year persuaded him to intervene. Boioannes (allied with Pandulf of Capua) marched on Dattus, who was garrisoning a tower in the territory of the

Duchy of Gaeta with papal troops. Dattus was captured and, on 15 June 1021, received the traditional Roman

poena cullei: he was tied up in a sack with a monkey, a rooster and a snake and thrown into the sea. In 1022, a large imperial army marched south in three detachments under Henry II,

Pilgrim of Cologne and

Poppo of Aquileia to attack Troia. Although Troia did not fall, the Lombard princes were allied with the Empire and Pandulf removed to a German prison; this ended the Lombard revolt.

Mercenary service, 1022–1046

In 1024, Norman mercenaries under

Ranulf Drengot were in the service of

Guaimar III when he and

Pandulf IV besieged

Pandulf V in Capua. In 1026, after an 18-month siege, Capua surrendered and Pandulf IV was reinstated as prince. During the next few years Ranulf would attach himself to Pandulf, but in 1029 he joined

Sergius IV of Naples (whom Pandulf expelled from

Naples in 1027, probably with Ranulf's assistance).

In 1029, Ranulf and Sergius recaptured Naples. In early 1030 Sergius gave Ranulf the

County of Aversa as a fief, the first Norman lordship in southern Italy.

[21] Sergius also gave his sister, the widow of the duke of Gaeta, in marriage to Ranulf.

[21] In 1034, however, Sergius' sister died and Ranulf returned to Pandulf. According to Amatus:

For the Normans never desired any of the Lombards to win a decisive victory, in case this should be to their disadvantage. But now supporting the one and then aiding the other, they prevented anyone being completely ruined.

Norman reinforcements and local miscreants, who found a welcome in Ranulf's camp with no questions asked, swelled Ranulf's numbers.

[21] There, Amatus observed that the

Norman language and customs welded a disparate group into the semblance of a nation. In 1035, the same year

William the Conqueror would become

Duke of Normandy,

Tancred of Hauteville's three eldest sons (

William "Iron Arm",

Drogo and

Humphrey) arrived in Aversa from

Normandy.

[22]

In 1037, or the summer of 1038

[21] (sources differ), Norman influence was further solidified when

Emperor Conrad II deposed Pandulf and invested Ranulf as Count of Aversa. In 1038 Ranulf invaded Capua, expanding his polity into one of the largest in southern Italy.

[21]

In 1038 Byzantine Emperor

Michael IV launched a military campaign into Muslim Sicily, with General

George Maniaches leading the Christian army against the

Saracens. The future king of Norway,

Harald Hardrada, commanded the

Varangian Guard in the expedition and Michael called on

Guaimar IV of Salerno and other Lombard lords to provide additional troops for the campaign. Guiamar sent 300 Norman knights from Aversa, including the three Hauteville brothers (who would achieve renown for their prowess in battle). William of Hauteville became known as William Bras-de-Fer ("William Iron Arm") for single-handedly killing the

emir of Syracuse during that city's siege. The Norman contingent would leave before the campaign's end due to the inadequate distribution of Saracen loot.

[22]

After the assassination of Catapan

Nikephoros Dokeianos at

Ascoli in 1040 the Normans elected

Atenulf, brother of Pandulf III of Benevento, their leader. On 16 March 1041, near

Venosa on the

Olivento, the Norman army tried to negotiate with Catapan

Michael Dokeianos; although they failed, they still defeated the Byzantine army in the

Battle of Olivento. On 4 May 1041 the Norman army, led by William Iron Arm, defeated the Byzantines again in the

Battle of Montemaggiore near Cannae (avenging the Norman defeat in the 1018 Battle of Cannae.

[22] Although the catapan summoned a large Varangian force from Bari, the battle was a rout; many of Michael's soldiers drowned in the

Ofanto while retreating.

[23]

On 3 September 1041 at the

Battle of Montepeloso, the Normans (nominally under Arduin and Atenulf) defeated Byzantine catepan

Exaugustus Boioannes and brought him to

Benevento. Around that time, Guaimar IV of Salerno began to attract the Normans. In February 1042, Atenulf negotiated the ransom of Exaugustus and then fled with the ransom money to Byzantine territory. He was replaced by

Argyrus, who was bribed to defect to the Byzantines after a few early victories.

The revolt, originally Lombard, had become Norman in character and leadership. In September 1042, the three principal Norman groups held a council in

Melfi which included

Ranulf Drengot,

Guaimar IV and William Iron Arm. William and the other leaders petitioned Guaimar to recognize their conquests, and William was acknowledged as the Norman leader in Apula (which included Melfi and the Norman garrison at

Troia). He received the title of

Count of Apulia from Guiamar, and (like Ranulf) was his vassal. Guaimar proclaimed himself Duke of Apulia and Calabria, although he was never formally invested as such by the Holy Roman Emperor. William was married to Guida (daughter of

Guy,

Duke of Sorrento and Guaimar's niece), strengthening the alliance between the Normans and Guaimar.

[24]

At Melfi in 1043, Guaimar divided the region (except for Melfi itself, which was to be governed on a republican model) into twelve baronies for the Norman leaders. William received

Ascoli,

Asclettin Drengot received

Acerenza,

Tristan received

Montepeloso,

Hugh Tubœuf received

Monopoli,

Peter received

Trani,

Drogo of Hauteville received

Venosa and Ranulf Drengot (now the independent Duke of Gaeta) received Siponto and

Monte Gargano.

[24]

During their reign William and Guaimar began the conquest of

Calabria in 1044, and built the castle of Stridula (near

Squillace). William was less successful in Apulia, where he was defeated in 1045 near

Taranto by Argyrus (although his brother, Drogo, conquered

Bovino). At William's death, the period of Norman mercenary service ended with the rise of two Norman principalities owing nominal allegiance to the Holy Roman Empire: the County of Aversa (later the

Principality of Capua) and the County of Apulia (later the

Duchy of Apulia).

County of Melfi, 1046–1059

The

stone castle at Melfi was constructed by the Normans where no fortress had previously stood. The present castle includes additions to a simple, rectangular Norman keep.

In 1046 Drogo entered Apulia and defeated the catepan,

Eustathios Palatinos, near

Taranto while his brother

Humphrey forced

Bari to conclude a treaty with the Normans. Also that year,

Richard Drengot arrived with 40 knights from Normandy and

Robert "Guiscard" Hauteville arrived with other Norman immigrants.

[25]

In 1047 Guaimar (who had supported Drogo's succession and the establishment of a Norman dynasty in the south) gave him his daughter,

Gaitelgrima, in marriage.

Emperor Henry III confirmed the county of Aversa in its fidelity to him and made Drogo his vassal, granting him the title

dux et magister Italiae comesque Normannorum totius Apuliae et Calabriae (duke and master of Italy and count of the Normans of all Apulia and Calabria, the first legitimate title for the Normans of Melfi).

[25] Henry did not confirm the other titles given during the 1042 council; he demoted Guiamar to "prince of Salerno", and Capua was bestowed upon

Pandulf IV for the third (and final) time.

[25] Henry, whose wife

Agnes had been mistreated by the Beneventans, authorised Drogo to conquer

Benevento for the imperial crown; he did so in 1053.

In 1048 Drogo commanded an expedition into Calabria via the valley of

Crati, near

Cosenza. He distributed the conquered territories in Calabria and gave his brother,

Robert Guiscard, a castle at

Scribla to guard the entrance to the recently conquered territory; Guiscard would later abandon it for a castle at

San Marco Argentano.

[25] Shortly thereafter he married the daughter of another Norman lord, who gave him 200 knights (furthering his military campaign in Calabria).

[26] In 1051 Drogo was assassinated by Byzantine conspirators

[26] and was succeeded by his brother, Humphrey.

[27] Humphrey's first challenge was to deal with papal opposition to the Normans.

[27] The Norman knights' treatment of the Lombards during Drogo's reign triggered more revolts.

[27] During the unrest, the Italo-Norman

John, Abbot of Fécamp was accosted on his return trip from Rome;

[27] he wrote to

Pope Leo IX:

The hatred of the Italians for the Normans has now reached such a pitch that it is almost impossible for any Norman, albeit a pilgrim, to journey in the towns of Italy, without being assailed, abducted, robbed, beaten, thrown in irons, even if fortunate enough not to die in a prison.

[28]

The pope and his supporters, including the future

Gregory VII, called for an army to oust the Normans from Italy.

[27]

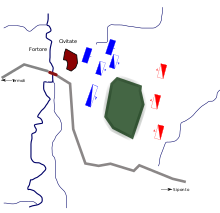

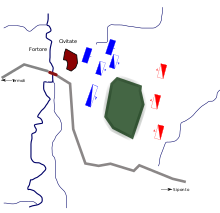

Battle plan of Civitate: Normans in red, papal coalition in blue

On 18 June 1053, Humphrey led the Norman armies against the combined forces of the pope and the

Holy Roman Empire. At the

Battle of Civitate the Normans destroyed the papal army and captured Leo IX, imprisoning him in Benevento (which had surrendered). Humphrey conquered

Oria,

Nardò, and

Lecce by the end of 1055. In 1054

Peter II, who succeeded Peter I in the region of

Trani, captured the city from the Byzantines. Humphrey died in 1057; he was succeeded by Guiscard, who ended his loyalty to the Empire and made himself a papal vassal in return for the title of duke.

[27]

County of Aversa, 1049–1098

During the 1050s and 1060s, there were two centres of Norman power in southern Italy: one at Melfi (under the Hautevilles) and another at Aversa (under the Drengots).

Richard Drengot became ruler of the County of Aversa in 1049, beginning a policy of territorial aggrandisement to compete with his Hauteville rivals. At first he warred with his Lombard neighbours, who included

Pandulf VI of Capua,

Atenulf I of Gaeta and

Gisulf II of Salerno. Richard pushed back the borders of Salerno until there was little left of the once-great principality but the city of

Salerno itself. Although he tried to extend his influence peacefully by betrothing his daughter to the oldest son of Atenulf of Gaeta, when the boy died before the marriage he still demanded the Lombard

dower from the boy's parents. When the duke refused, Richard seized

Aquino (one of Gaeta's few remaining fiefs) in 1058. However, the chronology of his conquest of Gaeta is confusing. Documents from 1058 and 1060 refer to

Jordan (Richard's oldest son) as

Duke of Gaeta, but these have been disputed as forgeries (since Atenulf was still duke when he died in 1062).

[29] After Atenulf's death, Richard and Jordan took over the rule of the duchy and allowed Atenulf's heir—

Atenulf II—to rule as their subject until 1064 (when Gaeta was fully incorporated into the Drengot principality). Richard and Jordan appointed puppet, usually Norman, dukes.

[30]

When the prince of

Capua died in 1057, Richard immediately besieged the

comune. This chronology is also unclear. Pandulf was succeeded at Capua by his brother,

Landulf VIII, who is recorded as prince until 12 May 1062. Richard and Jordan took the princely title in 1058, but apparently allowed Landulf to continue ruling beneath them for at least four years more. In 1059

Pope Nicholas II convened a

synod at Melfi confirming Richard as Count of Aversa and Prince of Capua, and Richard swore allegiance to the papacy for his holdings. The Drengots then made Capua their headquarters for ruling Aversa and Gaeta.

Richard and Jordan expanded their new Gaetan and Capuan territories northwards toward

Latium, into the

Papal States. In 1066 Richard marched on Rome, but was easily repelled. Jordan's tenure as Richard's successor marked an alliance with the papacy (which Richard had attempted), and the conquests of Capua ceased. When Jordan died in 1090, his young son

Richard II and his regents were unable to hold Capua. They were forced to flee the city by a Lombard,

Lando, who ruled it with popular support until he was forced out by the combined

Hauteville forces in the

siege of Capua in 1098; this ended Lombard rule in Italy.

Conquest of the Abruzzo, 1053–1105

In 1077 the last Lombard prince of

Benevento died, and in 1078 the pope appointed Robert Guiscard to succeed him. In 1081, however, Guiscard relinquished Benevento. By then, the principality comprised little more than Benevento and its environs; it had been reduced in size by Norman conquests during the previous decades, especially after the Battle of Civitate and after 1078. At Ceprano in June 1080 the pope again gave Guiscard control of Benevento, an attempt to halt Norman incursions into it and associated territory in the Abruzzi (which Guiscard's relatives had been appropriating).

After the Battle of Civitate, the Normans began the conquest of the Adriatic coast of Benevento.

Geoffrey of Hauteville, a brother of the Hauteville counts of Melfi, conquered the Lombard county of

Larino and stormed the castle

Morrone in the region of

Samnium-Guillamatum. Geoffrey's son,

Robert, united these conquests into a county,

Loritello, in 1061 and continued his expansion into Lombard Abruzzo. He conquered the Lombard county of Teate (modern

Chieti) and besieged

Ortona, which became the goal of Norman efforts in that region. Loritello soon reached as far north as the

Pescara and the Papal States. In 1078 Robert allied with Jordan of Capua to ravage the Papal Abruzzo, but after a 1080 treaty with

Pope Gregory VII they were obligated to respect papal territory. In 1100 Robert of Loritello extended his principality across the

Fortore, taking

Bovino and

Dragonara.

The conquest of the

Molise is poorly documented.

Boiano (the principal town) may have been conquered the year before the Battle of Civitate by Robert Guiscard, who had encircled the

Matese massif. The county of Boiano was bestowed on

Rudolf of Moulins. His grandson,

Hugh, expanded it eastward (occupying

Toro and

San Giovanni in Galdo) and westward (annexing the Capuan counties of

Venafro,

Pietrabbondante and

Trivento in 1105).

Conquest of Sicily, 1061–1091

See also:

Emirate of Sicily,

County of Sicily, and

Norman invasion of Malta

Roger I of Sicily

Roger I of Sicily at the 1063

battle of Cerami, victorious over 35,000

Saracens according to

Goffredo Malaterra.

After 250 years of Arab control, Sicily was inhabited by a mix of Christians, Arab Muslims, and Muslim converts at the time of its conquest by the Normans. Arab Sicily had a thriving trade network with the Mediterranean world, and was known in the Arab world as a luxurious and decadent place. It had originally been under the rule of the

Aghlabids and then the

Fatimids, but in 948 the

Kalbids wrested control of the island and held it until 1053. During the 1010s and 1020s, a series of succession crises paved the way for interference by the

Zirids of

Ifriqiya. Sicily was racked by turmoil as petty fiefdoms battled each other for supremacy. Into this, the Normans under Robert Guiscard and his younger brother

Roger Bosso came intending to conquer; the pope had conferred on Robert the title of "Duke of Sicily", encouraging him to seize Sicily from the Saracens.

Robert and Roger first invaded Sicily in May 1061, crossing from

Reggio di Calabria and besieging

Messina for control of the strategically vital

Strait of Messina. Roger crossed the strait first, landing unseen overnight and surprising the Saracen army in the morning. When Robert's troops landed later that day, they found themselves unopposed and Messina abandoned. Robert immediately fortified the city and allied himself with the

emir,

Ibn at-Timnah, against his rival

Ibn al-Hawas. Robert, Roger, and at-Timnah then marched into the centre of the island by way of

Rometta, which had remained loyal to at-Timnah. They passed through

Frazzanò and the

Pianura di Maniace (Plain of Maniakes), encountering resistance to their assault of

Centuripe.

Paternò fell quickly, and Robert brought his army to

Castrogiovanni (modern Enna, the strongest fortress in central Sicily). Although the garrison was defeated the citadel did not fall, and with winter approaching Robert returned to Apulia. Before leaving, he built a fortress at

San Marco d'Alunzio (the first Norman castle in Sicily). Roger returned in late 1061 and captured

Troina. In June 1063 he defeated a Muslim army at the

Battle of Cerami, securing the Norman foothold on the island.

Roger I receiving the keys of Palermo in 1071

Robert returned in 1064, bypassing Castrogiovanni on his way to

Palermo; this campaign was eventually called off. In August 1071, the Normans began a second and successful siege of Palermo. The city of Palermo was entered by the Normans on 7 January 1072 and three days later the defenders of the inner-city surrendered.

[31] Meanwhile, in 1066,

William the Conqueror had become the first Norman

King of England. Robert invested Roger as

Count of Sicily under the suzerainty of the Duke of Apulia. In a partition of the island with his brother Robert retained Palermo, half of Messina, and the largely Christian

Val Demone (leaving the rest, including what was not yet conquered, to Roger).

In 1077 Roger besieged

Trapani, one of the two remaining Saracen strongholds in the west of the island. His son,

Jordan, led a sortie which surprised guards of the garrison's livestock. With its food supply cut off, the city soon surrendered. In 1079

Taormina was besieged, and in 1081 Jordan, Robert de Sourval and Elias Cartomi conquered

Catania (a holding of the emir of

Syracuse) in another surprise attack.

Roger left Sicily in the summer of 1083 to assist his brother on the mainland; Jordan (whom he had left in charge) revolted, forcing him to return to Sicily and subjugate his son. In 1085, he was finally able to undertake a systematic campaign. On 22 May Roger approached Syracuse by sea, while Jordan led a small cavalry detachment 15 miles (24 km) north of the city. On 25 May, the navies of the count and the emir engaged in the harbour—where the latter was killed—while Jordan's forces besieged the city. The siege lasted throughout the summer, but when the city capitulated in March 1086 only

Noto was still under Saracen dominion. In February 1091 Noto yielded as well, and the conquest of Sicily was complete.

The

Palazzo dei Normanni was a 9th-century Arab palace in Sicily, converted by the Normans into their governing castle.

In 1091, Roger

invaded Malta and subdued the walled city of

Mdina. He imposed taxes on the islands, but allowed the Arab governors to continue their rule. In 1127 Roger II abolished the Muslim government, replacing it with Norman officials. Under Norman rule, the Arabic spoken by the Greek Christian islanders for centuries of Muslim domination became

Maltese.

Conquest of Amalfi and Salerno, 1073–1077

The fall of Amalfi and Salerno to Robert Guiscard were influenced by his wife,

Sichelgaita. Amalfi probably surrendered as a result of her negotiations,

[32] and Salerno fell when she stopped petitioning her husband on behalf of her brother (the prince of Salerno). The Amalfitans unsuccessfully subjected themselves to Prince Gisulf to avoid Norman suzerainty, but the states (whose histories had been joined since the 9th century) ultimately came under Norman control.

By summer 1076, through piracy and raids Gisulf II of Salerno incited the Normans to destroy him; that season, under Richard of Capua and Robert Guiscard the Normans united to besiege Salerno. Although Gisulf ordered his citizens to store two years' worth of food, he confiscated enough of it to starve his subjects. On 13 December 1076, the city submitted; the prince and his retainers retreated to the citadel, which fell in May 1077. Although Gisulf's lands and relics were confiscated, he remained at liberty. The Principality of Salerno had already been reduced to little more than the capital city and its environs by previous wars with

William of the Principate, Roger of Sicily and Robert Guiscard. However, the city was the most important in southern Italy and its capture was essential to the creation of a kingdom fifty years later.

In 1073

Sergius III of Amalfi died, leaving the infant

John III as his successor. Desiring protection in unstable times, the Amalfitans exiled the young duke and summoned Robert Guiscard that year.

[33] Amalfi, however, remained restless under Norman control. Robert's successor, Roger Borsa, took control of Amalfi in 1089 after expelling Gisulf (the deposed Prince of Salerno, whom the citizens had installed with papal aid). From 1092 to 1097 Amalfi did not recognise its Norman suzerain, apparently seeking Byzantine help;

[32] Marinus Sebaste was installed as ruler in 1096.

Robert's son Bohemond and his brother Roger of Sicily attacked Amalfi in 1097, but were repulsed. During this siege, the Normans began to be drawn by the

First Crusade. Marinus was defeated after Amalfitan noblemen defected to the Norman side and betrayed him in 1101. Amalfi revolted again in 1130, when

Roger II of Sicily demanded its loyalty. It was finally subdued in 1131 when

Admiral John marched on it by land and

George of Antioch blockaded it by sea, establishing a base on

Capri.

Byzantine–Norman wars, 1059–1085

Main article:

Byzantine–Norman wars

While most of Apulia (except the far south and Bari) had capitulated to the Normans in campaigns by the fraternal counts William, Drogo and Humphrey, much of Calabria remained in Byzantine hands at Robert Guiscard's 1057 succession. Calabria was first breached by William and Guaimar during the early 1040s, and Drogo installed Guiscard there during the early 1050s. However, Robert's early career in Calabria was spent in feudal infighting and robber baronage rather than organised subjugation of the Greek population.

He began his tenure with a Calabrian campaign. Briefly interrupted for the

Council of Melfi on 23 August 1059 (where he was invested as duke), he returned to Calabria—and his army's siege of

Cariati—later that year. The town capitulated at the duke's arrival, and

Rossano and

Gerace also fell before the end of the season. Of the peninsula's significant cities, only

Reggio remained in Byzantine hands when Robert returned to Apulia that winter. In Apulia, he temporarily removed the Byzantine garrison from

Taranto and

Brindisi. The duke returned to Calabria in 1060, primarily to launch a Sicilian expedition. Although the conquest of Reggio required an arduous siege, Robert's brother Roger had

siege engines prepared.

After the fall of Reggio the Byzantine garrison fled to Reggio's island citadel of

Scilla, where they were easily defeated. Roger's minor assault on Messina (across the strait) was repulsed, and Robert was called away by a large Byzantine force in Apulia sent by

Constantine X late in 1060. Under the catapan

Miriarch, the Byzantines retook Taranto, Brindisi,

Oria, and

Otranto; in January 1061, the Norman capital of Melfi was under siege. By May, however, the two brothers had expelled the Byzantines and calmed Apulia.

Norman progress in Sicily during Robert's expeditions to the Balkans: Capua, Apulia, Calabria, and the County of Sicily are Norman. The Emirate of Sicily, the

Duchy of Naples and lands in the Abruzzo (in the southern Duchy of Spoleto) are not yet conquered.

Geoffrey, son of Peter I of Trani, conquered

Otranto in 1063 and

Taranto (which he made his county seat) in 1064. In 1066 he organised an army for a marine attack on "Romania" (the Byzantine Balkans), but was halted near Bari by a recently landed army of Varangian auxiliaries under the catapan

Mabrica. Mabrica briefly retook Brindisi and Taranto, establishing a garrison at the former under

Nikephoros Karantenos (an experienced Byzantine soldier from the

Bulgar wars). Although the catapan was successful against the Normans in Italy, it was the last significant Byzantine threat. Bari, the capital of the Byzantine catapanate, was

besieged by the Normans beginning in August 1068; in April 1071 the city, the last Byzantine outpost in western Europe, fell.

After expelling the Byzantines from Apulia and Calabria (their

theme of

Langobardia), Robert Guiscard planned an attack on Byzantine possessions in Greece. The Byzantines had supported Robert's nephews,

Abelard and

Herman (the dispossessed son of Count Humphrey), in their insurrection against Robert; they had also supported

Henry, Count of Monte Sant'Angelo, who recognised Byzantine suzerainty in

his county, against him.

In 1073-75 Robert's vassal,

Peter II of Trani, led a Balkan expedition against the

Kingdom of Croatia's

Dalmatian lands. Peter's cousin

Amico (son of

Walter of Giovinazzo) attacked the islands of

Rab and

Cres, taking Croatian king

Petar Krešimir IV captive. Although Petar was ransomed by the

Bishop of Cres, he died shortly afterwards and was buried in the church of

Saint Stephen in the

Fortress of Klis.

Robert undertook his first Balkan expedition in May 1081, leaving Brindisi with about 16,000 troops. By February 1082 he captured

Corfu and

Durazzo, defeating the

Emperor Alexius I at the

Battle of Dyrrhachium the previous October. Robert's son

Mark Bohemond temporarily controlled

Thessaly, unsuccessfully trying to retain the 1081–82 conquests in Robert's absence. The duke returned in 1084 to restore them, occupying Corfu and

Kephalonia before his death from a fever on 15 July 1085. The village of

Fiskardo on

Cephalonia is named after Robert. Bohemond did not continue pursuing Greek conquests, returning to Italy to dispute Robert's succession with his half-brother

Roger Borsa.

Conquest of Naples, 1077–1139

The

Duchy of Naples, nominally a Byzantine possession, was one of the last southern Italian states to be attacked by the Normans. Since Sergius IV asked for Ranulf Drengot's help during the 1020s, with brief exceptions the dukes of Naples were allied with the Normans of Aversa and Capua. Beginning in 1077, the incorporation of Naples into the Hauteville state took sixty years to complete.

In summer 1074, hostilities flared up between Richard of Capua and Robert Guiscard.

Sergius V of Naples allied with the latter, making his city a supply centre for Guiscard's troops. This pitted him against Richard, who was supported by Gregory VII. In June Richard briefly besieged Naples; Richard, Robert and Sergius soon began negotiations with Gregory, mediated by

Desiderius of Montecassino.

In 1077 Naples was again besieged by Richard of Capua, with a naval blockade by Robert Guiscard. Richard died during the siege in 1078, after the deathbed lifting of his excommunication. The siege was ended by his successor, Jordan, to insinuate himself with the papacy (which had made peace with Duke Sergius).

In 1130, the

Antipope Anacletus II crowned Roger II of Sicily king and declared the fief of Naples part of his kingdom.

[34] In 1131, Roger demanded from the citizens of Amalfi the defences of their city and the keys to their castle. When they refused,

Sergius VII of Naples initially prepared to aid them with a fleet; George of Antioch blockaded Naples' port with a large armada and Sergius, cowed by the suppression of the Amalfitans, submitted to Roger. According to the chronicler

Alexander of Telese, Naples "which, since Roman times, had hardly ever been conquered by the sword now submitted to Roger on the strength of a mere report (i.e. Amalfi's fall)."

In 1134 Sergius supported the rebellion of

Robert II of Capua and

Ranulf II of Alife, but avoided direct confrontation with Roger and paid homage to the king after the fall of Capua. On 24 April 1135 a

Pisan fleet with 8,000 reinforcements, captained by Robert of Capua, anchored in Naples and the duchy was the centre of the revolt against Roger II for the next two years. Sergius, Robert and Ranulf were besieged in Naples until the spring of 1136, by which time starvation was widespread. According to historian (and rebel sympathiser)

Falco of Benevento Sergius and the Neapolitans did not relent, "preferring to die of hunger than to bare their necks to the power of an evil king." The naval blockade's failure to prevent Sergius and Robert from twice bringing supplies from Pisa exemplified Roger's inadequacy. When a relief army commanded by

Emperor Lothair II marched to Naples, the siege was lifted. Although the emperor left the following year, in return for a pardon Sergius re-submitted to Roger in Norman feudal homage. On 30 October 1137, the last Duke of Naples died in the king's service at the

Battle of Rignano.

The defeat at Rignano enabled the Norman conquest of Naples, since Sergius died without heir and the Neapolitan nobility could not reach a succession agreement. However, it was two years between Sergius' death and Naples' incorporation by Sicily. The nobility apparently ruled during the interim, which may have been the final period of Neapolitan independence from Norman rule.

[34] During this period Norman landowners first appear in Naples, although the Pisans (enemies of Roger II) retained their alliance with the duchy and Pisa may have sustained its independence until 1139. That year, Roger absorbed Naples into his kingdom;

Pope Innocent II and the Neapolitan nobility acknowledged Roger's young son,

Alfonso of Hauteville, as duke.

Kingdom of Sicily, 1130–1198

Main article:

Kingdom of Sicily

Although the conquest of Sicily was primarily military, Robert and Roger also signed treaties with the Muslims to obtain land. Hindered by Sicily's hilly terrain and a relatively small army, the brothers sought influential, worn-down Muslim leaders to sign the treaties (offering peace and protection for land and titles). Because Sicily was conquered by a unified command, Roger's authority was not challenged by other conquerors and he maintained power over his Greek, Arab, Lombard and Norman subjects. Latin Christianity was introduced to the island, and its ecclesiastical organisation was overseen by Roger with papal approval.

Sees were established at Palermo (with

metropolitan authority), Syracuse and

Agrigento. After its elevation to a

Kingdom of Sicily in 1130, Sicily became the centre of Norman power with

Palermo as capital. The Kingdom was created on Christmas Day, 1130, by

Roger II of Sicily, with the agreement of

Pope Innocent II, who united the lands Roger had inherited from his father

Roger I of Sicily.

[35]

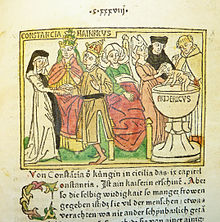

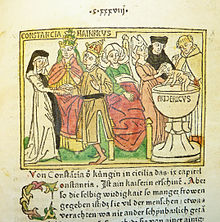

Woodcut illustration of

Constance of Sicily, her husband

Emperor Henry VI and her son

Frederick II

These areas included the

Maltese Archipelago, which was conquered from the

Arabs of the Emirates of Sicily; the

Duchy of Apulia and the

County of Sicily, which had belonged to his cousin

William II, Duke of Apulia, until William's death in 1127; and the other Norman vassals.

[36]

With the invasion of

Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor on behalf of his wife,

Constance, the daughter of Roger II, eventually prevailed and the kingdom fell in 1194 to the

House of Hohenstaufen. Through Constance, the

Hauteville blood was passed to

Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor and king of Sicily in 1198.

Encastellation

See also:

Norman-Arab-Byzantine culture

Early Norman castle at Adrano

The Norman conquest of southern Italy began an infusion of

Romanesque (specifically

Norman) architecture. Some castles were expanded on existing Lombard, Byzantine and Arab structures, while others were original constructions. The castles drew on local craftsmanship, and retained distinctive elements of their non-Norman origins. Latin cathedrals were built in lands recently converted from Byzantine Christianity or Islam, in a Romanesque style influenced by

Byzantine and

Islamic designs.

Norman administration was centralised, complex and bureaucratic compared with other contemporary western European systems. Public buildings, such as palaces, were common in larger cities (notably Palermo); these structures, in particular, demonstrate the influence of Siculo-Arab culture.

The Normans rapidly began the construction, expansion and renovation of castles in southern Italy. Most were original or based on pre-existing Lombard structures, although some were built on Byzantine or (in Sicily) Arab foundations. By the end of the Norman period, most

wooden castles were converted to stone.

After the Lombard castle at Melfi, which was conquered by the Normans early and augmented with a surviving, rectangular

donjon late in the 11th century, Calabria was the first province affected by Norman

encastellation. In 1046 William Iron Arm began construction of Stridula (a large castle near

Squillace), and by 1055 Robert Guiscard built three castles: at

Rossano, on the site of a Byzantine fortress; at Scribla, the seat of his fief guarding the pass of the

Val di Crati, and at

San Marco Argentano (donjon built in 1051) near

Cosenza.

[37] In 1058,

Scalea was built on a seaside cliff.

Guiscard was a major castle-builder after his accession to the Apulian countship, building a castle at

Gargano with pentagonal towers known as the Towers of Giants. Later,

Henry, Count of Monte Sant'Angelo built a castle at nearby

Castelpagano. In the

Molise the Normans built many fortresses into the naturally defensible terrain, such as Santa Croce and Ferrante. The region of a line running from

Terracina to

Termoli has the greatest density of Norman castles in Italy.

[38] Many sites were originally

Samnite strongholds reused by the

Romans and their successors; the Normans called such a fortress a

castellum vetus (old castle). Many Molisian castles have walls integrated into the mountains and ridges, and much of the quickly erected masonry demonstrates that the Normans introduced the

opus gallicum into the Molise.

[39]

The encastellation of Sicily was begun at the behest of the native Greek inhabitants.

[40] In 1060, they asked Guiscard to construct a castle at

Aluntium. The first Norman building on Sicily, San Marco d'Alunzio (named after Guiscard's first castle at Argentano in Calabria), was erected; its ruins survive. Petralia Soprana was then built near

Cefalù, followed by a castle at

Troina in 1071; in 1073 a castle was built at

Mazara (extant ruins) and another at

Paternò (restored ruins).

[40] At

Adrano (or Aderno) the Normans built a plain, rectangular tower whose floor plan illustrates 11th-century Norman design. An outside stairway leads to the first-storey entrance, and the interior is divided lengthwise down the middle into a

great hall on one side and two rooms (a chapel and chamber) on the other.

[41] Other fortifications in Sicily were appropriated from the Arabs, and the palatial and

cathedral architecture of cities such as Palermo has obvious Arab features. Arab artistic influence in Sicily mirrors the Lombard influence in the Mezzogiorno.