Khal Drogo

Veoma poznat

- Poruka

- 12.571

Битка и масакр римских легија у Тевтобуршкој шуми су поприлично обрађени кроз књиге, текстове, документарне филмове као и једну играну серију (о чему ћу у каснијим постовима) ове године, догађај којем у њемачком народу дају велику важност, малтене приказују као судбоносну битку која је све промијенила, но како то и бива има ту подоста произвољног тумачења које води у робовању погрешним увјерењима.

Зато ми је намјера да кроз тему сагледамо сам догађај, битку, оно што је претходило бици, као и касније догађаје и какве су биле посљедице.

Сама битка и масакр су се одиграли вјероватно у 3 дана 9-11.сепрембра. 9.године.н.е. (овдје)

И завршила је катастрофом за римске легије.

Да би разумјели ове догађаје ваља се вратити мало у прошлост.

Римљани су већ раније тежиште операције и експанзије пренијели на десну обалу Рајне која је једно вријеме била природна граница.

У успјешној кампањом 12-8.године п.н.е. коју је предводио Друз I потчинили су својој власти германска племена на том простору

Као залог вјерности Риму владар једног од најбројнијих германских племена Херуска, Сегимер дао је своје синове као таоце, уједно да у Риму буду одгојени и стекну образовање. Синови су упамћени по римским именима Арминије и Флавије.

Римљани јесу потчинили својој власти нека германска племена, међутим отпор других гермамских племена наставио се наредних година.

Посебмо је ојачало племе Маркомана предвођени амбициозним краљем Марободом, који су постали опасни ривал Риму.

Маробод је имао снажну и добро увјежбану армију, по Велеију Петеркулу (овдје, погл. 109);

Војска Маркомана је пролазила кроз темељиту војну обуку тако да се по квалитети и организацији нису били далеко од римског ратног строја.

Зато је Рим 6.године н.е. предузео војни поход против Маркомана са намјером да помјере границе царства са Дунава на Лабу.

Тиберије који је имао врховну команду је развио план напада великом војском из два правца. Један правац напада ће водити бивши конзул и врло способан заповједник Сентиус Сатурнин из смјера данашњег града Маинца у Њемачкој, који је повео 3 легије, 17., 18. и 19. легију (ПС; ове 3 легије су важне за ову тему), кроз област племена Кати (касније Бохемија) коју су Маркомани покорили ударио је са запада на Маробода.

Другу већу војску, најмање 8 легија, из правца Норика водио је лично Тиберије.

Римска војска бјеше велика 60-65.000 легионара, 10.000 коњаника те 10-20.000 помоћних снага, добро вођена од искусних стратега, бјеше пред великом побједом, но тада су примили вијест о избијању устанка у Илирику.

Тиберије је морао брзо реаговати, кампања и непријатељства су хитно прекинута, Маробод је рекао “охо, хо, ово добро испаде“, на брзину је склопљен мировни споразум, све Тиберијеве снаге које су пошле из правца Норика су повучене у Илирик, ту су се придружиле легије из Тракије и Македоније, и наредне 3 године на гушењу побуне у Илирику ангажовано је 15 легија (од 28 са колико је Рим располагао) и још толико помоћних снага, никад Рим није већу војску ангажовао на гушењу побуне и највећа римска војска од времена пунских ратова. Поменуте 3 легије (XVII, XVIII и XIX) на челу са Сатурнином су остале у Германији како би контролисали германска племена уз Рајну.

Сатурнин бива враћен у Рим а замјењује га Публије Квинтилије Вар који је преузео команду над овим легијама.

Зато ми је намјера да кроз тему сагледамо сам догађај, битку, оно што је претходило бици, као и касније догађаје и какве су биле посљедице.

Сама битка и масакр су се одиграли вјероватно у 3 дана 9-11.сепрембра. 9.године.н.е. (овдје)

Battle of the Teutoburg Forest

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (German: Schlacht im Teutoburger Wald, Hermannsschlacht, or Varusschlacht), described as the Varian Disaster (Latin: Clades Variana) by Roman historians, took place in the Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE, when an alliance of Germanic peoples ambushed and destroyed three Roman legions and their auxiliaries, led by Publius Quinctilius Varus. The alliance was led by Arminius, a Germanic officer of Varus's auxilia. Arminius had acquired Roman citizenship and had received a Roman military education, which enabled him to deceive the Roman commander methodically and anticipate the Roman army's tactical responses.

Despite several successful campaigns and raids by the Romans in the years after the battle, they never again attempted to conquer the Germanic territories east of the Rhine, except for Germania Superior.

Background

Main article: Early Imperial campaigns in Germania

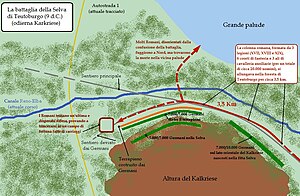

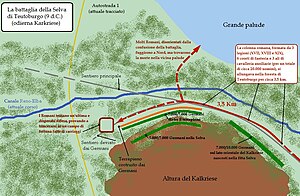

Map showing the defeat of Publius Quinctilius Varus in the Teutoburg Forest

Invasions of Drusus I in 12–8 BCE

Invasions of Tiberius and Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus in circa 3 BCE–6 CE.

Following the attacks of Drusus I in 11–9 BCE, Arminius, along with his brother Flavus,[6][7] was sent to Rome as tribute by their father, Segimerus the Conqueror,[8][9] chieftain of the noblest house in the tribe of the Cherusci. Arminius then spent his youth in Rome as a hostage, where he received a military education, and was even given the rank of Equestrian. During Arminius' absence, Segimerus was declared a coward by the other Germanic chieftains, because he had submitted to Roman rule, a crime punishable by death under Germanic law. Between 11 BCE and 4 CE, the hostility and suspicion between the allied Germanic peoples deepened. Trade and political accords between the warlords deteriorated.[a] In 4 CE the Roman general (and later emperor) Tiberius entered Germania and subjugated the Cananefates in Germania Inferior, the Chattihttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Teutoburg_Forest#cite_note-13 near the upper Weser River and the Bructeri south of the Teutoburg Forest. After these conquests he led his army across the Weser.

In early 6 CE Legatus Gaius Sentius Saturninus[12][13] and Consul Legatus Marcus Aemilius Lepidus led a massive army of 65,000 heavy infantry legionaries, 10,000–20,000 cavalrymen, archers, 10,000–20,000 civilians (13 legions and their entourage, totalling around 100,000 men) in an offensive operation against Maroboduus,[14][15] the king of the Marcomanni, who were a tribe of the Suebi.[c] Later in 6 CE, leadership of the Roman force was turned over to Publius Quinctilius Varus, a nobleman and experienced administrative official from a patrician family[14] who was related to the Imperial family.[17] He was assigned to consolidate the new province of Germania in the autumn of that year.[14]

Tiberius was then forced to turn his attention to the Bellum Batonianum, also known as the Great Illyrian Revolt, which broke out in the province of Illyricum. Led by Bato the Daesitiate,[18] Bato the Breucian,[19] Pinnes of Pannonia,[20] and elements of the Marcomanni, it lasted nearly four years. Tiberius was forced to stop his campaign against Maroboduus and recognise him as king[21] so that he could then send his eight legions (VIII Augustan, XV Apollonian, XX Victorious Valerian, XXI Predator, XIII Twin, XIV Twin, XVI Gallic and an unknown unit)[22] to crush the rebellion in the Balkans.

Nearly half of all Roman legions in existence were sent to the Balkans to end the revolt, which was itself triggered by constant neglect, endemic food shortages, high taxes, and harsh behaviour on the part of the Roman tax collectors. This campaign, led by Tiberius and Quaestor Legatus Germanicus under Emperor Augustus, was one of the most difficult, and most crucial, in the history of the Roman Empire. Due to this massive redeployment of available legions, when Varus was named Legatus Augusti pro praetore in Germania, only three legions were available to him.

Varus' name and deeds were well known beyond the empire because of his ruthlessness and crucifixion of insurgents. While he was feared by the people, he was highly respected by the Roman senate. On the Rhine, he was in command of the XVII, XVIII, and XIX legions. These had previously been led by General Gaius Sentius Saturninus, who had been sent back to Rome after being awarded an ornamenta triumphalia.[23] The other two legions in the winter-quarters of the army at castrum Moguntiacum[24] were led by Varus' nephew, Lucius Nonius Asprenas[22] and perhaps Lucius Arruntius.

After his return from Rome, Arminius became a trusted advisor to Varus,[25] but in secret he forged an alliance of Germanic peoples that had traditionally been enemies. These included the Cherusci,[14] Marsi,[14] Chatti,[14] Bructeri,[14] Chauci, Sicambri, and remaining elements of the Suebi, who had been defeated by Caesar in the Battle of Vosges. These five were some of the fifty Germanic groups at the time.[26] Using the collective outrage over Varus' tyrannous insolence and wanton cruelty to the conquered,[24] Arminius was able to unite the disorganized groups who had submitted in sullen hatred to the Roman dominion, and maintain the alliance until the most opportune moment to strike.[27]

The Teutoburg Forest on a foggy and rainy day

Between 6 and 9 CE, the Romans were forced to move eight of eleven legions present in Germania east of the Rhine river to crush a rebellion in the Balkans, leaving Varus with only three legions to face the Germans.[22] This represented the perfect opportunity for Arminius to defeat Varus.[21] While Varus was on his way from his summer camp west of the River Weser to winter headquarters near the Rhine, he heard reports of a local rebellion, reports which had been fabricated by Arminius.[15] Edward Shepherd Creasy writes that "This was represented to Varus as an occasion which required his prompt attendance on the spot; but he was kept in studied ignorance of its being part of a concerted national rising; and he still looked on Arminius as his submissive vassal".[28]

Varus decided to quell this uprising immediately, expediting his response by taking a detour through territory that was unfamiliar to the Romans. Arminius, who accompanied him, directed him along a route that would facilitate an ambush.[15] Another Cheruscan nobleman, Segestes, brother of Segimerus and unwilling father-in-law to Arminius,[9][29] warned Varus the night before the Roman forces departed, allegedly suggesting that Varus should apprehend Arminius, along with other Germanic leaders whom he identified as participants in the planned uprising. His warning, however, was dismissed as stemming from the personal feud between Segestes and Arminius. Arminius then left under the pretext of drumming up Germanic forces to support the Roman campaign. Once free from prying eyes, he immediately led his troops in a series of attacks on the surrounding Roman garrisons.

Recent archaeological finds place the battle at Kalkriese Hill in Osnabrück county, Lower Saxony.[14] On the basis of Roman accounts, the Romans were marching northwest from what is now the city of Detmold, passing east of Osnabrück after camping in the area, prior to the attack.

Battles

Autumn in Teutoburg Forest

Varus' forces included his three legions (Legio XVII, Legio XVIII and Legio XIX), six cohorts of auxiliary troops (non-citizens or allied troops) and three squadrons of cavalry (alae). Most of these lacked combat experience, both with regard to Germanic fighters, and under the prevalent local conditions. The Roman forces were not marching in combat formation, and were interspersed with large numbers of camp followers. As they entered the forest northeast of Osnabrück, they found the track narrow and muddy. According to Dio Cassius a violent storm had also arisen. He also writes that Varus neglected to send out reconnaissance parties ahead of the main body of troops.

The line of march was now stretched out perilously long—between 15 and 20 kilometres (9.3 and 12.4 mi).[25] It was in this state when it came under attack by Germanic warriors armed with light swords, large lances and narrow-bladed short spears called fremae. The attackers surrounded the entire Roman army, and rained down javelins on the intruders.[30] Arminius, recalling his education in Rome, understood his enemies' tactics, and was able to direct his troops to counter them effectively by using locally superior numbers against the dispersed Roman legions. The Romans managed to set up a fortified night camp, and the next morning broke out into the open country north of the Wiehen Hills, near the modern town of Ostercappeln. The break-out was accompanied by heavy losses to the Roman survivors, as was a further attempt to escape by marching through another forested area, as the torrential rains continued.

Reconstruction of the improvised fortifications prepared by the Germanic coalition for the final phase of the Varus battle near Kalkriese

The Romans undertook a night march to escape, but marched into another trap that Arminius had set, at the foot of Kalkriese Hill. There a sandy, open strip on which the Romans could march was constricted by the hill, so that there was a gap of only about 100 metres between the woods and the swampland at the edge of the Great Bog. The road was further blocked by a trench, and, towards the forest, an earthen wall had been built along the roadside, permitting the Germanic alliance to attack the Romans from cover. The Romans made a desperate attempt to storm the wall, but failed, and the highest-ranking officer next to Varus, Legatus Numonius Vala, abandoned the troops by riding off with the cavalry. His retreat was in vain, however, as he was overtaken by the Germanic cavalry and killed shortly thereafter, according to Velleius Paterculus. The Germanic warriors then stormed the field and slaughtered the disintegrating Roman forces. Varus committed suicide,[25] and Velleius reports that one commander, Praefectus Ceionius, surrendered, then later took his own life,[31] while his colleague Praefectus Eggius died leading his doomed troops.

Roman casualties have been estimated at 15,000–20,000 dead, and many of the officers were said to have taken their own lives by falling on their swords in the approved manner.[25] Tacitus wrote that many officers were sacrificed by the Germanic forces as part of their indigenous religious ceremonies, cooked in pots and their bones used for rituals.[32] Others were ransomed, and some common soldiers appear to have been enslaved.

Germanic warriors storm the field, Varusschlacht, 1909

All Roman accounts stress the completeness of the Roman defeat. The finds at Kalkriese of 6,000 pieces of Roman equipment, but only a single item that is clearly Germanic (part of a spur), suggests few Germanic losses. However, the victors would most likely have removed the bodies of their fallen, and their practice of burying their warriors' battle gear with them would have also contributed to the lack of Germanic relics. Additionally, several thousand Germanic soldiers were deserting militiamen and wore Roman armour, and thus would appear to be "Roman" in the archaeological digs. It is also known that the Germanic peoples wore perishable organic material, such as leather, and less metal.

The victory was followed by a clean sweep of all Roman forts, garrisons and cities (of which there were at least two) east of the Rhine; the remaining two Roman legions in Germania, commanded by Varus' nephew Lucius Nonius Asprenas, were content to try to hold the Rhine. One fort, Aliso, most likely located in today's Haltern am See,[33] fended off the Germanic alliance for many weeks, perhaps even a few months. After the situation became untenable, the garrison under Lucius Caedicius, accompanied by survivors of Teutoburg Forest, broke through the siege, and reached the Rhine. They resisted long enough for Lucius Nonius Asprenas to organize the Roman defence on the Rhine with two legions and Tiberius to arrive with a new army, preventing Arminius from crossing the Rhine and invading Gaul.[34][35]

Aftermath

Political situation in Germania after the battle of the Teutoburg Forest. In pink the anti-Roman Germanic coalition led by Arminius. In dark green, territories still directly held by the Romans, in yellow the Roman client states

Upon hearing of the defeat, the Emperor Augustus, according to the Roman historian Suetonius in The Twelve Caesars, was so shaken that he stood butting his head against the walls of his palace, repeatedly shouting:

The legion numbers XVII and XIX were not used again by the Romans (Legio XVIII was raised again under Nero, but finally disbanded under Vespasian). This was in contrast to other legions that were reestablished after suffering defeat. Another example of permanent disbandment was the XXII Deiotariana legion, which may have ceased to exist after incurring heavy losses when deployed against Jewish rebels during the Bar Kokba revolt (132–136 CE) in Judea.

The battle abruptly ended the period of triumphant Roman expansion that followed the end of the Civil Wars forty years earlier. Augustus' stepson Tiberius took effective control, and prepared for the continuation of the war. Legio II Augusta, XX Valeria Victrix and XIII Gemina were sent to the Rhine to replace the lost legions.

Arminius sent Varus' severed head to Maroboduus, king of the Marcomanni, the other most powerful Germanic ruler, with the offer of an anti-Roman alliance. Maroboduus declined, sending the head to Rome for burial, and remained neutral throughout the ensuing war. Only thereafter did a brief, inconclusive war break out between the two Germanic leaders.[36]

Roman retaliation

Germanicus' campaign against the Germanic coalition

The Roman commander Germanicus was the opponent of Arminius in 14–16 CE

Though the shock at the slaughter was enormous, the Romans immediately began a slow, systematic process of preparing for the reconquest of the country. In 14 CE, just after Augustus' death and the accession of his heir and stepson Tiberius, a massive raid was conducted by the new emperor's nephew Germanicus. He attacked the Marsi with the element of surprise. The Bructeri, Tubanti and Usipeti were roused by the attack and ambushed Germanicus on the way to his winter quarters, but were defeated with heavy losses.[37][38]

The next year was marked by two major campaigns and several smaller battles with a large army estimated at 55,000–70,000 men, backed by naval forces. In spring 15 CE, Legatus Caecina Severus invaded the Marsi a second time with about 25,000–30,000 men, causing great havoc. Meanwhile, Germanicus' troops had built a fort on Mount Taunus from where he marched with about 30,000–35,000 men against the Chatti. Many of the men fled across a river and dispersed themselves in the forests. Germanicus next marched on Mattium (caput gentis) and burned it to the ground.[39][40] After initial successful skirmishes in summer 15 CE, including the capture of Arminius' wife Thusnelda,[41] the army visited the site of the first battle. According to Tacitus, they found heaps of bleached bones and severed skulls nailed to trees, which they buried, "...looking on all as kinsfolk and of their own blood...". At a location Tacitus calls the pontes longi ("long causeways"), in boggy lowlands somewhere near the Ems, Arminius' troops attacked the Romans. Arminius initially caught Germanicus' cavalry in a trap, inflicting minor casualties, but the Roman infantry reinforced the rout and checked them. The fighting lasted for two days, with neither side achieving a decisive victory. Germanicus' forces withdrew and returned to the Rhine.[42][43][d]

Under Germanicus, the Romans marched another army, along with allied Germanic auxiliaries, into Germania in 16 CE. He forced a crossing of the Weser near modern Minden, suffering some losses to a Germanic skirmishing force, and forced Arminius' army to stand in open battle at Idistaviso in the Battle of the Weser River. Germanicus' legions inflicted huge casualties on the Germanic armies while sustaining only minor losses. A final battle was fought at the Angrivarian Wall west of modern Hanover, repeating the pattern of high Germanic fatalities, which forced them to flee beyond the Elbe.[46][47] Germanicus, having defeated the forces between the Rhine and the Elbe, then ordered Caius Silius to march against the Chatti with a mixed force of three thousand cavalry and thirty thousand infantry and lay waste to their territory, while Germanicus, with a larger army, invaded the Marsi for the third time and devastated their land, encountering no resistance.[48]

With his main objectives reached and winter approaching, Germanicus ordered his army back to their winter camps, with the fleet incurring some damage from a storm in the North Sea.[49] After a few more raids across the Rhine, which resulted in the recovery of two of the three legions' eagles lost in 9 CE,[50] Tiberius ordered the Roman forces to halt and withdraw across the Rhine. Germanicus was recalled to Rome and informed by Tiberius that he would be given a triumph and reassigned to a new command.[51][52][53]

Germanicus' campaign had been taken to avenge the Teutoburg slaughter and also partially in reaction to indications of mutinous intent amongst his troops. Arminius, who had been considered a very real threat to stability by Rome, was now defeated. Once his Germanic coalition had been broken and honour avenged, the huge cost and risk of keeping the Roman army operating beyond the Rhine was not worth any likely benefit to be gained.[25] Tacitus, with some bitterness, claims that Tiberius' decision to recall Germanicus was driven by his jealousy of the glory Germanicus had acquired, and that an additional campaign the next summer would have concluded the war and facilitated a Roman occupation of territories between the Rhine and the Elbe.[54][55]

Later campaigns

Roman coin showing the Aquilae on display in the Temple of Mars the Avenger in Rome

The third legionary standard was recovered in 41 CE by Publius Gabinius from the Chauci during the reign of Claudius, brother of Germanicus.[56] Possibly the recovered aquilae were placed within the Temple of Mars Ultor ("Mars the Avenger"), the ruins of which stand today in the Forum of Augustus by the Via dei Fori Imperiali in Rome.

The last chapter was recounted by the historian Tacitus. Around 50 CE, bands of Chatti invaded Roman territory in Germania Superior, possibly an area in Hesse east of the Rhine that the Romans appear to have still held, and began to plunder. The Roman commander, Publius Pomponius Secundus, and a legionary force supported by Roman cavalry recruited auxiliaries from the Vangiones and Nemetes. They attacked the Chatti from both sides and defeated them, and joyfully found and liberated Roman prisoners, including some from Varus' legions who had been held for 40 years.[57]

Impact on Roman expansion

Further information: Limes Germanicus § Augustus

Roman Limes and modern boundaries.

From the time of the rediscovery of Roman sources in the 15th century the Battles of the Teutoburg Forest have been seen as a pivotal event resulting in the end of Roman expansion into northern Europe. This theory became prevalent in the 19th century, and formed an integral part of the mythology of German nationalism.

More recently some scholars questioned this interpretation, advancing a number of reasons why the Rhine was a practical boundary for the Roman Empire, and more suitable than any other river in Germania.[58] Logistically, armies on the Rhine could be supplied from the Mediterranean via the Rhône, Saône and Mosel, with a brief stretch of portage. Armies on the Elbe, on the other hand, would have to have been supplied either by extensive overland routes or ships travelling the hazardous Atlantic seas. Economically, the Rhine was already supporting towns and sizeable villages at the time of the Gallic conquest. Northern Germania was far less developed, possessed fewer villages, and had little food surplus and thus a far lesser capacity for tribute. Thus the Rhine was both significantly more accessible from Rome and better suited to supply sizeable garrisons than the regions beyond. There were also practical reasons to fall back from the limits of Augustus' expansionism in this region. The Romans were mostly interested in conquering areas that had a high degree of self-sufficiency which could provide a tax base for them to extract from. Most of Germania Magna did not have the higher level of urbanism at this time as in comparison with some Celtic Gallic settlements, which were in many ways already integrated into the Roman trade network in the case of southern Gaul. In a cost/benefit analysis, the prestige to be gained by conquering more territory was outweighed by the lack of financial benefits accorded to conquest.[59][60]

The Teutoburg Forest myth is noteworthy in 19th century Germanic interpretations as to why the "march of the Roman Empire" was halted, but in reality Roman punitive campaigns into Germania continued even after that disaster, and they were intended less for conquest or expansion than they were to force the Germanic alliance into some kind of political structure that would be compliant with Roman diplomatic efforts.[61] The most famous of those incursions, led by the Roman emperor Maximinus Thrax, resulted in a Roman victory in 235 CE at the Battle at the Harzhorn Hill, which is located in the modern German state of Lower Saxony, east of the Weser river, between the towns of Kalefeld and Bad Gandersheim.[62] After the Marcomannic Wars, the Romans even managed to occupy the provinces of Marcomannia and Sarmatia, corresponding to modern Czech Republic, Slovakia and Bavaria/Austria/Hungary north of Danube. Final plans to annex those territories were discarded by Commodus deeming the occupation of the region too expensive for the imperial treasury.[63][64][65]

After Arminius was defeated and dead, having been murdered in 21 CE by opponents within his own tribe, Rome tried to control Germania beyond the Limes indirectly, by appointing client kings. Italicus, a nephew of Arminius, was appointed king of the Cherusci, Vangio and Sido became vassal princes of the powerful Suebi,[66][67] and the Quadian client king Vannius was imposed as a ruler of the Marcomanni.[68][69] Between 91 and 92 during the reign of emperor Domitian, the Romans sent a military detachment to assist their client Lugii against the Suebi in what is now Poland.[70]

Roman controlled territory was limited to the modern states of Austria, Baden-Württemberg, southern Bavaria, southern Hesse, Saarland and the Rhineland as Roman provinces of Noricum,[71] Raetia[72] and Germania.[73] The Roman provinces in western Germany, Germania Inferior (with the capital situated at Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium, modern Cologne) and Germania Superior (with its capital at Mogontiacum, modern Mainz), were formally established in 85 CE, after a long period of military occupation beginning in the reign of the emperor Augustus.[74] Nonetheless, the Severan-era historian Cassius Dio is emphatic that Varus had been conducting the latter stages of full colonization of a greater German province,[75] which has been partially confirmed by recent archaeological discoveries such as the Varian-era Roman provincial settlement at Waldgirmes Forum.

Site of the battle

Further information: Kalkriese

The archeological site at Kalkriese hill

Schleuderblei (Sling projectiles) found by Major Tony Clunn in Summer 1988, sparked new excavations[76]

The Roman ceremonial face mask found at Kalkriese

The theories about the location of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest have emerged in large numbers especially since the beginning of the 16th century, when the Tacitus works Germania and Annales were rediscovered. The assumptions about the possible place of the battle are based essentially on place names and river names, as well as on the description of the topography by the ancient writers, on investigations of the prehistoric road network, and on archaeological finds. Only a few assumptions are scientifically based theories.

The prehistorian and provincial archaeologist Harald Petrikovits combined the several hundred theories in 1966 into four units:[77]

For almost 2,000 years, the site of the battle was unidentified. The main clue to its location was an allusion to the saltus Teutoburgiensis in section i.60–62 of Tacitus' Annals, an area "not far" from the land between the upper reaches of the Lippe and Ems rivers in central Westphalia. During the 19th century, theories as to the site abounded, and the followers of one theory successfully argued for a long wooded ridge called the Osning, near Bielefeld. This was then renamed the Teutoburg Forest.[78]

Late 20th-century research and excavations were sparked by finds by a British amateur archaeologist, Major Tony Clunn, who was casually prospecting at Kalkriese Hill, 52°26′29″N 8°08′26″E) with a metal detector in the hope of finding "the odd Roman coin". He discovered coins from the reign of Augustus (and none later), and some ovoid leaden Roman sling bolts. Kalkriese is a village administratively part of the city of Bramsche, on the north slope fringes of the Wiehen, a ridge-like range of hills in Lower Saxony north of Osnabrück. This site, some 100 km north west of Osning, was first suggested by the 19th-century historian Theodor Mommsen, renowned for his fundamental work on Roman history.

Initial systematic excavations were carried out by the archaeological team of the Kulturhistorisches Museum Osnabrück under the direction of Professor Wolfgang Schlüter from 1987. Once the dimensions of the project had become apparent, a foundation was created to organise future excavations and to build and operate a museum on the site, and to centralise publicity and documentation. Since 1990 the excavations have been directed by Susanne Wilbers-Rost.

Excavations have revealed battle debris along a corridor almost 24 km (15 miles) from east to west and little more than a mile wide. A long zig-zagging wall of peat turves and packed sand had apparently been constructed beforehand: concentrations of battle debris in front of it and a dearth behind it testify to the Romans' inability to breach the Germans' strong defence. Human remains appear to corroborate Tacitus' account of the Roman legionaries' later burial.[79] Coins minted with the countermark VAR, distributed by Varus, also support the identification of the site. As a result, Kalkriese is now perceived to be an event of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest.

The Varusschlacht Museum und Park Kalkriese includes a large outdoor area with trails leading to a re-creation of part of the earthen wall from the battle and other outdoor exhibits. An observation tower, which holds most of the indoor exhibits, allows visitors to get an overview of the battle site. A second building includes the ticket centre, museum store and a restaurant. The museum houses a large number of artefacts found at the site, including fragments of studded sandals legionaries lost, spearheads, and a Roman officer's ceremonial face-mask, which was originally silver-plated.

Alternative theories on the battle's location

Although the majority of evidence has the battle taking place east and north of Osnabrück and the end at Kalkriese Hill, some scholars and others still adhere to older theories. Moreover, there is controversy among Kalkriese adherents themselves as to the details.

The German historians Peter Kehne and Reinhard Wolters believe that the battle was probably in the Detmold area, and that Kalkriese is the site of one of the battles in 15 CE. This theory is, however, in contradiction to Tacitus' account.

A number of authors, including the archaeologists Susanne Wilbers-Rost and Günther Moosbauer, historian Ralf Jahn, and British author Adrian Murdoch (see below), believe that the Roman army approached Kalkriese from roughly due east, from Minden, North Rhine-Westphalia, not from south of the Wiehen Hills (i.e., from Detmold). This would have involved a march along the northern edge of the Wiehen Hills, and the army would have passed through flat, open country, devoid of the dense forests and ravines described by Cassius Dio. Historians such as Gustav-Adolf Lehmann and Boris Dreyer counter that Cassius Dio's description is too detailed and differentiated to be thus dismissed.

Tony Clunn (see below), the discoverer of the battlefield, and a "southern-approach" proponent, believes that the battered Roman army regrouped north of Ostercappeln, where Varus committed suicide, and that the remnants were finally overcome at the Kalkriese Gap.

Peter Oppitz argues for a site in Paderborn, some 120 km south of Kalkriese. Based on a reinterpretation of the writings of Tacitus, Paterculus, and Florus and a new analysis of those of Cassius Dio, he proposes that an ambush took place in Varus's summer camp during a peaceful meeting between the Roman commanders and the Germans.[80]

In popular culture

Main article: Hermannsdenkmal

The Hermannsdenkmal circa 1900

The legacy of the Germanic victory was resurrected with the recovery of the histories of Tacitus in the 15th century, when the figure of Arminius, now known as "Hermann" (a mistranslation of the name "Armin" which has often been incorrectly attributed to Martin Luther), became a nationalistic symbol of Pan-Germanism. From then, Teutoburg Forest has been seen as a pivotal clash that ended Roman expansion into northern Europe. This notion became especially prevalent in the 19th century, when it formed an integral part of the mythology of German nationalism.

In 1808 the German Heinrich von Kleist's play Die Hermannsschlacht aroused anti-Napoleonic sentiment, even though it could not be performed under occupation. In 1847, Josef Viktor von Scheffel wrote a lengthy song, "Als die Römer frech geworden" ("When the Romans got cheeky"), relating the tale of the battle with somewhat gloating humour. Copies of the text are found on many souvenirs available at the Detmold monument.

The battle had a profound effect on 19th century German nationalism along with the histories of Tacitus; the Germans, at that time still divided into many states, identified with the Germanic peoples as shared ancestors of one "German people" and came to associate the imperialistic Napoleonic French and Austro-Hungarian forces with the invading Romans, destined for defeat.

As a symbol of unified Romantic nationalism, the Hermannsdenkmal, a monument to Hermann surmounted by a statue, was erected in a forested area near Detmold, believed at that time to be the site of the battle. Paid for largely out of private funds, the monument remained unfinished for decades and was not completed until 1875, after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 unified the country. The completed monument was then a symbol of conservative German nationalism. The battle and the Hermannsdenkmal monument are commemorated by the similar Hermann Heights Monument in New Ulm, Minnesota, US, erected by the Sons of Hermanni, a support organisation for German immigrants to the United States. Hermann, Missouri, US, claims Hermann (Arminius) as its namesake and a third statue of Hermann was dedicated there in a ceremony on 24 September 2009, celebrating the 2,000th anniversary of Teutoburg Forest.

In Germany, where since the end of World War II there has been a strong aversion to nationalistic celebration of the past, such tones have disappeared from German textbooks.[26] Commemoration of the battle's 2,000th anniversary in 2009 was muted.[26] According to Der Spiegel, "The old nationalism has been replaced by an easy-going patriotism that mainly manifests itself at sporting events like the soccer World Cup."[26]

| Battle of the Teutoburg Forest | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Part of the Early Imperial campaigns in Germania | |||||||||

Cenotaph of Marcus Caelius, 1st centurion of XVIII, who "fell in the war of Varus" (bello Variano). Reconstructed inscription: "To Marcus Caelius, son of Titus, of the Lemonian district, from Bologna, first centurion of the eighteenth legion. 53 1⁄2 years old. He fell in the Varian War. His freedman's bones may be interred here. Publius Caelius, son of Titus, of the Lemonian district, his brother, erected (this monument)."[1] | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Allied Germanic peoples (Cherusci, Marsi, Chatti, Bructeri, Angrivarii, Chauci and Sicambri) |

| ||||||||

| Arminius Segimer | Publius Quinctilius Varus † Marcus Caelius † | ||||||||

| Unknown, but estimated at 15,000[2] to 20,000 | 14,000–22,752[3] Unknown non-combatants[3] | ||||||||

| Unknown, but moderate | 16,000[4] to 20,000 dead[5] Some others enslaved |

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (German: Schlacht im Teutoburger Wald, Hermannsschlacht, or Varusschlacht), described as the Varian Disaster (Latin: Clades Variana) by Roman historians, took place in the Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE, when an alliance of Germanic peoples ambushed and destroyed three Roman legions and their auxiliaries, led by Publius Quinctilius Varus. The alliance was led by Arminius, a Germanic officer of Varus's auxilia. Arminius had acquired Roman citizenship and had received a Roman military education, which enabled him to deceive the Roman commander methodically and anticipate the Roman army's tactical responses.

Despite several successful campaigns and raids by the Romans in the years after the battle, they never again attempted to conquer the Germanic territories east of the Rhine, except for Germania Superior.

Background

Main article: Early Imperial campaigns in Germania

Map showing the defeat of Publius Quinctilius Varus in the Teutoburg Forest

Invasions of Drusus I in 12–8 BCE

Invasions of Tiberius and Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus in circa 3 BCE–6 CE.

Following the attacks of Drusus I in 11–9 BCE, Arminius, along with his brother Flavus,[6][7] was sent to Rome as tribute by their father, Segimerus the Conqueror,[8][9] chieftain of the noblest house in the tribe of the Cherusci. Arminius then spent his youth in Rome as a hostage, where he received a military education, and was even given the rank of Equestrian. During Arminius' absence, Segimerus was declared a coward by the other Germanic chieftains, because he had submitted to Roman rule, a crime punishable by death under Germanic law. Between 11 BCE and 4 CE, the hostility and suspicion between the allied Germanic peoples deepened. Trade and political accords between the warlords deteriorated.[a] In 4 CE the Roman general (and later emperor) Tiberius entered Germania and subjugated the Cananefates in Germania Inferior, the Chattihttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Teutoburg_Forest#cite_note-13 near the upper Weser River and the Bructeri south of the Teutoburg Forest. After these conquests he led his army across the Weser.

In early 6 CE Legatus Gaius Sentius Saturninus[12][13] and Consul Legatus Marcus Aemilius Lepidus led a massive army of 65,000 heavy infantry legionaries, 10,000–20,000 cavalrymen, archers, 10,000–20,000 civilians (13 legions and their entourage, totalling around 100,000 men) in an offensive operation against Maroboduus,[14][15] the king of the Marcomanni, who were a tribe of the Suebi.[c] Later in 6 CE, leadership of the Roman force was turned over to Publius Quinctilius Varus, a nobleman and experienced administrative official from a patrician family[14] who was related to the Imperial family.[17] He was assigned to consolidate the new province of Germania in the autumn of that year.[14]

Tiberius was then forced to turn his attention to the Bellum Batonianum, also known as the Great Illyrian Revolt, which broke out in the province of Illyricum. Led by Bato the Daesitiate,[18] Bato the Breucian,[19] Pinnes of Pannonia,[20] and elements of the Marcomanni, it lasted nearly four years. Tiberius was forced to stop his campaign against Maroboduus and recognise him as king[21] so that he could then send his eight legions (VIII Augustan, XV Apollonian, XX Victorious Valerian, XXI Predator, XIII Twin, XIV Twin, XVI Gallic and an unknown unit)[22] to crush the rebellion in the Balkans.

Nearly half of all Roman legions in existence were sent to the Balkans to end the revolt, which was itself triggered by constant neglect, endemic food shortages, high taxes, and harsh behaviour on the part of the Roman tax collectors. This campaign, led by Tiberius and Quaestor Legatus Germanicus under Emperor Augustus, was one of the most difficult, and most crucial, in the history of the Roman Empire. Due to this massive redeployment of available legions, when Varus was named Legatus Augusti pro praetore in Germania, only three legions were available to him.

Varus' name and deeds were well known beyond the empire because of his ruthlessness and crucifixion of insurgents. While he was feared by the people, he was highly respected by the Roman senate. On the Rhine, he was in command of the XVII, XVIII, and XIX legions. These had previously been led by General Gaius Sentius Saturninus, who had been sent back to Rome after being awarded an ornamenta triumphalia.[23] The other two legions in the winter-quarters of the army at castrum Moguntiacum[24] were led by Varus' nephew, Lucius Nonius Asprenas[22] and perhaps Lucius Arruntius.

After his return from Rome, Arminius became a trusted advisor to Varus,[25] but in secret he forged an alliance of Germanic peoples that had traditionally been enemies. These included the Cherusci,[14] Marsi,[14] Chatti,[14] Bructeri,[14] Chauci, Sicambri, and remaining elements of the Suebi, who had been defeated by Caesar in the Battle of Vosges. These five were some of the fifty Germanic groups at the time.[26] Using the collective outrage over Varus' tyrannous insolence and wanton cruelty to the conquered,[24] Arminius was able to unite the disorganized groups who had submitted in sullen hatred to the Roman dominion, and maintain the alliance until the most opportune moment to strike.[27]

The Teutoburg Forest on a foggy and rainy day

Between 6 and 9 CE, the Romans were forced to move eight of eleven legions present in Germania east of the Rhine river to crush a rebellion in the Balkans, leaving Varus with only three legions to face the Germans.[22] This represented the perfect opportunity for Arminius to defeat Varus.[21] While Varus was on his way from his summer camp west of the River Weser to winter headquarters near the Rhine, he heard reports of a local rebellion, reports which had been fabricated by Arminius.[15] Edward Shepherd Creasy writes that "This was represented to Varus as an occasion which required his prompt attendance on the spot; but he was kept in studied ignorance of its being part of a concerted national rising; and he still looked on Arminius as his submissive vassal".[28]

Varus decided to quell this uprising immediately, expediting his response by taking a detour through territory that was unfamiliar to the Romans. Arminius, who accompanied him, directed him along a route that would facilitate an ambush.[15] Another Cheruscan nobleman, Segestes, brother of Segimerus and unwilling father-in-law to Arminius,[9][29] warned Varus the night before the Roman forces departed, allegedly suggesting that Varus should apprehend Arminius, along with other Germanic leaders whom he identified as participants in the planned uprising. His warning, however, was dismissed as stemming from the personal feud between Segestes and Arminius. Arminius then left under the pretext of drumming up Germanic forces to support the Roman campaign. Once free from prying eyes, he immediately led his troops in a series of attacks on the surrounding Roman garrisons.

Recent archaeological finds place the battle at Kalkriese Hill in Osnabrück county, Lower Saxony.[14] On the basis of Roman accounts, the Romans were marching northwest from what is now the city of Detmold, passing east of Osnabrück after camping in the area, prior to the attack.

Battles

Autumn in Teutoburg Forest

Varus' forces included his three legions (Legio XVII, Legio XVIII and Legio XIX), six cohorts of auxiliary troops (non-citizens or allied troops) and three squadrons of cavalry (alae). Most of these lacked combat experience, both with regard to Germanic fighters, and under the prevalent local conditions. The Roman forces were not marching in combat formation, and were interspersed with large numbers of camp followers. As they entered the forest northeast of Osnabrück, they found the track narrow and muddy. According to Dio Cassius a violent storm had also arisen. He also writes that Varus neglected to send out reconnaissance parties ahead of the main body of troops.

The line of march was now stretched out perilously long—between 15 and 20 kilometres (9.3 and 12.4 mi).[25] It was in this state when it came under attack by Germanic warriors armed with light swords, large lances and narrow-bladed short spears called fremae. The attackers surrounded the entire Roman army, and rained down javelins on the intruders.[30] Arminius, recalling his education in Rome, understood his enemies' tactics, and was able to direct his troops to counter them effectively by using locally superior numbers against the dispersed Roman legions. The Romans managed to set up a fortified night camp, and the next morning broke out into the open country north of the Wiehen Hills, near the modern town of Ostercappeln. The break-out was accompanied by heavy losses to the Roman survivors, as was a further attempt to escape by marching through another forested area, as the torrential rains continued.

Reconstruction of the improvised fortifications prepared by the Germanic coalition for the final phase of the Varus battle near Kalkriese

The Romans undertook a night march to escape, but marched into another trap that Arminius had set, at the foot of Kalkriese Hill. There a sandy, open strip on which the Romans could march was constricted by the hill, so that there was a gap of only about 100 metres between the woods and the swampland at the edge of the Great Bog. The road was further blocked by a trench, and, towards the forest, an earthen wall had been built along the roadside, permitting the Germanic alliance to attack the Romans from cover. The Romans made a desperate attempt to storm the wall, but failed, and the highest-ranking officer next to Varus, Legatus Numonius Vala, abandoned the troops by riding off with the cavalry. His retreat was in vain, however, as he was overtaken by the Germanic cavalry and killed shortly thereafter, according to Velleius Paterculus. The Germanic warriors then stormed the field and slaughtered the disintegrating Roman forces. Varus committed suicide,[25] and Velleius reports that one commander, Praefectus Ceionius, surrendered, then later took his own life,[31] while his colleague Praefectus Eggius died leading his doomed troops.

Roman casualties have been estimated at 15,000–20,000 dead, and many of the officers were said to have taken their own lives by falling on their swords in the approved manner.[25] Tacitus wrote that many officers were sacrificed by the Germanic forces as part of their indigenous religious ceremonies, cooked in pots and their bones used for rituals.[32] Others were ransomed, and some common soldiers appear to have been enslaved.

Germanic warriors storm the field, Varusschlacht, 1909

All Roman accounts stress the completeness of the Roman defeat. The finds at Kalkriese of 6,000 pieces of Roman equipment, but only a single item that is clearly Germanic (part of a spur), suggests few Germanic losses. However, the victors would most likely have removed the bodies of their fallen, and their practice of burying their warriors' battle gear with them would have also contributed to the lack of Germanic relics. Additionally, several thousand Germanic soldiers were deserting militiamen and wore Roman armour, and thus would appear to be "Roman" in the archaeological digs. It is also known that the Germanic peoples wore perishable organic material, such as leather, and less metal.

The victory was followed by a clean sweep of all Roman forts, garrisons and cities (of which there were at least two) east of the Rhine; the remaining two Roman legions in Germania, commanded by Varus' nephew Lucius Nonius Asprenas, were content to try to hold the Rhine. One fort, Aliso, most likely located in today's Haltern am See,[33] fended off the Germanic alliance for many weeks, perhaps even a few months. After the situation became untenable, the garrison under Lucius Caedicius, accompanied by survivors of Teutoburg Forest, broke through the siege, and reached the Rhine. They resisted long enough for Lucius Nonius Asprenas to organize the Roman defence on the Rhine with two legions and Tiberius to arrive with a new army, preventing Arminius from crossing the Rhine and invading Gaul.[34][35]

Aftermath

Political situation in Germania after the battle of the Teutoburg Forest. In pink the anti-Roman Germanic coalition led by Arminius. In dark green, territories still directly held by the Romans, in yellow the Roman client states

Upon hearing of the defeat, the Emperor Augustus, according to the Roman historian Suetonius in The Twelve Caesars, was so shaken that he stood butting his head against the walls of his palace, repeatedly shouting:

Quintili Vare, legiones redde! (Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!)

The legion numbers XVII and XIX were not used again by the Romans (Legio XVIII was raised again under Nero, but finally disbanded under Vespasian). This was in contrast to other legions that were reestablished after suffering defeat. Another example of permanent disbandment was the XXII Deiotariana legion, which may have ceased to exist after incurring heavy losses when deployed against Jewish rebels during the Bar Kokba revolt (132–136 CE) in Judea.

The battle abruptly ended the period of triumphant Roman expansion that followed the end of the Civil Wars forty years earlier. Augustus' stepson Tiberius took effective control, and prepared for the continuation of the war. Legio II Augusta, XX Valeria Victrix and XIII Gemina were sent to the Rhine to replace the lost legions.

Arminius sent Varus' severed head to Maroboduus, king of the Marcomanni, the other most powerful Germanic ruler, with the offer of an anti-Roman alliance. Maroboduus declined, sending the head to Rome for burial, and remained neutral throughout the ensuing war. Only thereafter did a brief, inconclusive war break out between the two Germanic leaders.[36]

Roman retaliation

Germanicus' campaign against the Germanic coalition

The Roman commander Germanicus was the opponent of Arminius in 14–16 CE

Though the shock at the slaughter was enormous, the Romans immediately began a slow, systematic process of preparing for the reconquest of the country. In 14 CE, just after Augustus' death and the accession of his heir and stepson Tiberius, a massive raid was conducted by the new emperor's nephew Germanicus. He attacked the Marsi with the element of surprise. The Bructeri, Tubanti and Usipeti were roused by the attack and ambushed Germanicus on the way to his winter quarters, but were defeated with heavy losses.[37][38]

The next year was marked by two major campaigns and several smaller battles with a large army estimated at 55,000–70,000 men, backed by naval forces. In spring 15 CE, Legatus Caecina Severus invaded the Marsi a second time with about 25,000–30,000 men, causing great havoc. Meanwhile, Germanicus' troops had built a fort on Mount Taunus from where he marched with about 30,000–35,000 men against the Chatti. Many of the men fled across a river and dispersed themselves in the forests. Germanicus next marched on Mattium (caput gentis) and burned it to the ground.[39][40] After initial successful skirmishes in summer 15 CE, including the capture of Arminius' wife Thusnelda,[41] the army visited the site of the first battle. According to Tacitus, they found heaps of bleached bones and severed skulls nailed to trees, which they buried, "...looking on all as kinsfolk and of their own blood...". At a location Tacitus calls the pontes longi ("long causeways"), in boggy lowlands somewhere near the Ems, Arminius' troops attacked the Romans. Arminius initially caught Germanicus' cavalry in a trap, inflicting minor casualties, but the Roman infantry reinforced the rout and checked them. The fighting lasted for two days, with neither side achieving a decisive victory. Germanicus' forces withdrew and returned to the Rhine.[42][43][d]

Under Germanicus, the Romans marched another army, along with allied Germanic auxiliaries, into Germania in 16 CE. He forced a crossing of the Weser near modern Minden, suffering some losses to a Germanic skirmishing force, and forced Arminius' army to stand in open battle at Idistaviso in the Battle of the Weser River. Germanicus' legions inflicted huge casualties on the Germanic armies while sustaining only minor losses. A final battle was fought at the Angrivarian Wall west of modern Hanover, repeating the pattern of high Germanic fatalities, which forced them to flee beyond the Elbe.[46][47] Germanicus, having defeated the forces between the Rhine and the Elbe, then ordered Caius Silius to march against the Chatti with a mixed force of three thousand cavalry and thirty thousand infantry and lay waste to their territory, while Germanicus, with a larger army, invaded the Marsi for the third time and devastated their land, encountering no resistance.[48]

With his main objectives reached and winter approaching, Germanicus ordered his army back to their winter camps, with the fleet incurring some damage from a storm in the North Sea.[49] After a few more raids across the Rhine, which resulted in the recovery of two of the three legions' eagles lost in 9 CE,[50] Tiberius ordered the Roman forces to halt and withdraw across the Rhine. Germanicus was recalled to Rome and informed by Tiberius that he would be given a triumph and reassigned to a new command.[51][52][53]

Germanicus' campaign had been taken to avenge the Teutoburg slaughter and also partially in reaction to indications of mutinous intent amongst his troops. Arminius, who had been considered a very real threat to stability by Rome, was now defeated. Once his Germanic coalition had been broken and honour avenged, the huge cost and risk of keeping the Roman army operating beyond the Rhine was not worth any likely benefit to be gained.[25] Tacitus, with some bitterness, claims that Tiberius' decision to recall Germanicus was driven by his jealousy of the glory Germanicus had acquired, and that an additional campaign the next summer would have concluded the war and facilitated a Roman occupation of territories between the Rhine and the Elbe.[54][55]

Later campaigns

Roman coin showing the Aquilae on display in the Temple of Mars the Avenger in Rome

The third legionary standard was recovered in 41 CE by Publius Gabinius from the Chauci during the reign of Claudius, brother of Germanicus.[56] Possibly the recovered aquilae were placed within the Temple of Mars Ultor ("Mars the Avenger"), the ruins of which stand today in the Forum of Augustus by the Via dei Fori Imperiali in Rome.

The last chapter was recounted by the historian Tacitus. Around 50 CE, bands of Chatti invaded Roman territory in Germania Superior, possibly an area in Hesse east of the Rhine that the Romans appear to have still held, and began to plunder. The Roman commander, Publius Pomponius Secundus, and a legionary force supported by Roman cavalry recruited auxiliaries from the Vangiones and Nemetes. They attacked the Chatti from both sides and defeated them, and joyfully found and liberated Roman prisoners, including some from Varus' legions who had been held for 40 years.[57]

Impact on Roman expansion

Further information: Limes Germanicus § Augustus

Roman Limes and modern boundaries.

From the time of the rediscovery of Roman sources in the 15th century the Battles of the Teutoburg Forest have been seen as a pivotal event resulting in the end of Roman expansion into northern Europe. This theory became prevalent in the 19th century, and formed an integral part of the mythology of German nationalism.

More recently some scholars questioned this interpretation, advancing a number of reasons why the Rhine was a practical boundary for the Roman Empire, and more suitable than any other river in Germania.[58] Logistically, armies on the Rhine could be supplied from the Mediterranean via the Rhône, Saône and Mosel, with a brief stretch of portage. Armies on the Elbe, on the other hand, would have to have been supplied either by extensive overland routes or ships travelling the hazardous Atlantic seas. Economically, the Rhine was already supporting towns and sizeable villages at the time of the Gallic conquest. Northern Germania was far less developed, possessed fewer villages, and had little food surplus and thus a far lesser capacity for tribute. Thus the Rhine was both significantly more accessible from Rome and better suited to supply sizeable garrisons than the regions beyond. There were also practical reasons to fall back from the limits of Augustus' expansionism in this region. The Romans were mostly interested in conquering areas that had a high degree of self-sufficiency which could provide a tax base for them to extract from. Most of Germania Magna did not have the higher level of urbanism at this time as in comparison with some Celtic Gallic settlements, which were in many ways already integrated into the Roman trade network in the case of southern Gaul. In a cost/benefit analysis, the prestige to be gained by conquering more territory was outweighed by the lack of financial benefits accorded to conquest.[59][60]

The Teutoburg Forest myth is noteworthy in 19th century Germanic interpretations as to why the "march of the Roman Empire" was halted, but in reality Roman punitive campaigns into Germania continued even after that disaster, and they were intended less for conquest or expansion than they were to force the Germanic alliance into some kind of political structure that would be compliant with Roman diplomatic efforts.[61] The most famous of those incursions, led by the Roman emperor Maximinus Thrax, resulted in a Roman victory in 235 CE at the Battle at the Harzhorn Hill, which is located in the modern German state of Lower Saxony, east of the Weser river, between the towns of Kalefeld and Bad Gandersheim.[62] After the Marcomannic Wars, the Romans even managed to occupy the provinces of Marcomannia and Sarmatia, corresponding to modern Czech Republic, Slovakia and Bavaria/Austria/Hungary north of Danube. Final plans to annex those territories were discarded by Commodus deeming the occupation of the region too expensive for the imperial treasury.[63][64][65]

After Arminius was defeated and dead, having been murdered in 21 CE by opponents within his own tribe, Rome tried to control Germania beyond the Limes indirectly, by appointing client kings. Italicus, a nephew of Arminius, was appointed king of the Cherusci, Vangio and Sido became vassal princes of the powerful Suebi,[66][67] and the Quadian client king Vannius was imposed as a ruler of the Marcomanni.[68][69] Between 91 and 92 during the reign of emperor Domitian, the Romans sent a military detachment to assist their client Lugii against the Suebi in what is now Poland.[70]

Roman controlled territory was limited to the modern states of Austria, Baden-Württemberg, southern Bavaria, southern Hesse, Saarland and the Rhineland as Roman provinces of Noricum,[71] Raetia[72] and Germania.[73] The Roman provinces in western Germany, Germania Inferior (with the capital situated at Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium, modern Cologne) and Germania Superior (with its capital at Mogontiacum, modern Mainz), were formally established in 85 CE, after a long period of military occupation beginning in the reign of the emperor Augustus.[74] Nonetheless, the Severan-era historian Cassius Dio is emphatic that Varus had been conducting the latter stages of full colonization of a greater German province,[75] which has been partially confirmed by recent archaeological discoveries such as the Varian-era Roman provincial settlement at Waldgirmes Forum.

Site of the battle

Further information: Kalkriese

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The archeological site at Kalkriese hill

Schleuderblei (Sling projectiles) found by Major Tony Clunn in Summer 1988, sparked new excavations[76]

The Roman ceremonial face mask found at Kalkriese

The theories about the location of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest have emerged in large numbers especially since the beginning of the 16th century, when the Tacitus works Germania and Annales were rediscovered. The assumptions about the possible place of the battle are based essentially on place names and river names, as well as on the description of the topography by the ancient writers, on investigations of the prehistoric road network, and on archaeological finds. Only a few assumptions are scientifically based theories.

The prehistorian and provincial archaeologist Harald Petrikovits combined the several hundred theories in 1966 into four units:[77]

- according to the northern theory on the northern edge of the Wiehen Hills and Weser Hills

- according to Lippe theory in the eastern half of the Teutoburg Forest or between this and the Weser river

- according to the Münsterland theory south of the Teutoburg Forest near Beckum or just to the east of it and

- according to the southern theory in the hill country southeast of the Westphalian Lowland.

For almost 2,000 years, the site of the battle was unidentified. The main clue to its location was an allusion to the saltus Teutoburgiensis in section i.60–62 of Tacitus' Annals, an area "not far" from the land between the upper reaches of the Lippe and Ems rivers in central Westphalia. During the 19th century, theories as to the site abounded, and the followers of one theory successfully argued for a long wooded ridge called the Osning, near Bielefeld. This was then renamed the Teutoburg Forest.[78]

Late 20th-century research and excavations were sparked by finds by a British amateur archaeologist, Major Tony Clunn, who was casually prospecting at Kalkriese Hill, 52°26′29″N 8°08′26″E) with a metal detector in the hope of finding "the odd Roman coin". He discovered coins from the reign of Augustus (and none later), and some ovoid leaden Roman sling bolts. Kalkriese is a village administratively part of the city of Bramsche, on the north slope fringes of the Wiehen, a ridge-like range of hills in Lower Saxony north of Osnabrück. This site, some 100 km north west of Osning, was first suggested by the 19th-century historian Theodor Mommsen, renowned for his fundamental work on Roman history.

Initial systematic excavations were carried out by the archaeological team of the Kulturhistorisches Museum Osnabrück under the direction of Professor Wolfgang Schlüter from 1987. Once the dimensions of the project had become apparent, a foundation was created to organise future excavations and to build and operate a museum on the site, and to centralise publicity and documentation. Since 1990 the excavations have been directed by Susanne Wilbers-Rost.

Excavations have revealed battle debris along a corridor almost 24 km (15 miles) from east to west and little more than a mile wide. A long zig-zagging wall of peat turves and packed sand had apparently been constructed beforehand: concentrations of battle debris in front of it and a dearth behind it testify to the Romans' inability to breach the Germans' strong defence. Human remains appear to corroborate Tacitus' account of the Roman legionaries' later burial.[79] Coins minted with the countermark VAR, distributed by Varus, also support the identification of the site. As a result, Kalkriese is now perceived to be an event of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest.

The Varusschlacht Museum und Park Kalkriese includes a large outdoor area with trails leading to a re-creation of part of the earthen wall from the battle and other outdoor exhibits. An observation tower, which holds most of the indoor exhibits, allows visitors to get an overview of the battle site. A second building includes the ticket centre, museum store and a restaurant. The museum houses a large number of artefacts found at the site, including fragments of studded sandals legionaries lost, spearheads, and a Roman officer's ceremonial face-mask, which was originally silver-plated.

Alternative theories on the battle's location

Although the majority of evidence has the battle taking place east and north of Osnabrück and the end at Kalkriese Hill, some scholars and others still adhere to older theories. Moreover, there is controversy among Kalkriese adherents themselves as to the details.

The German historians Peter Kehne and Reinhard Wolters believe that the battle was probably in the Detmold area, and that Kalkriese is the site of one of the battles in 15 CE. This theory is, however, in contradiction to Tacitus' account.

A number of authors, including the archaeologists Susanne Wilbers-Rost and Günther Moosbauer, historian Ralf Jahn, and British author Adrian Murdoch (see below), believe that the Roman army approached Kalkriese from roughly due east, from Minden, North Rhine-Westphalia, not from south of the Wiehen Hills (i.e., from Detmold). This would have involved a march along the northern edge of the Wiehen Hills, and the army would have passed through flat, open country, devoid of the dense forests and ravines described by Cassius Dio. Historians such as Gustav-Adolf Lehmann and Boris Dreyer counter that Cassius Dio's description is too detailed and differentiated to be thus dismissed.

Tony Clunn (see below), the discoverer of the battlefield, and a "southern-approach" proponent, believes that the battered Roman army regrouped north of Ostercappeln, where Varus committed suicide, and that the remnants were finally overcome at the Kalkriese Gap.

Peter Oppitz argues for a site in Paderborn, some 120 km south of Kalkriese. Based on a reinterpretation of the writings of Tacitus, Paterculus, and Florus and a new analysis of those of Cassius Dio, he proposes that an ambush took place in Varus's summer camp during a peaceful meeting between the Roman commanders and the Germans.[80]

In popular culture

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

- In the 1792 historical novel Marcus Flaminius by Cornelia Knight, the main character is a survivor of the battle.[81]

- Die Hermannsschlacht is an 1808 drama by Heinrich von Kleist based on the events of the battle.

- The battle and its aftermath feature in both the novel by Robert Graves and television series I, Claudius. In the novel and TV series, Cassius Chaerea (the praetorian guardsman who later murdered the mad Emperor Caligula) is portrayed as one of the few Roman survivors. The Emperor Augustus is shown as being devastated by the shocking defeat, shouting "Varus, give me back my legions!"; in the television adaptation, this is modified to "Quinctilus Varus, where are my Eagles?!"

- Die Sendung mit der Maus, a re-enactment for children's television using Playmobil toys to represent the Roman legions.[82]

- Give Me Back My Legions! is a 2009 historical novel by Harry Turtledove. It covers the events of Teutoburg Forest from the viewpoints of different major characters.

- Wolves of Rome is a 2016 historical novel by Valerio Massimo Manfredi. First published in Italian in 2016 as “Teutoburgo”, republished in English in 2018. It is a fictional recount of the life of Armin (Hermann) and the events of Teutoburg Forest.

- German folk metal Heilung included the song "Schlammschlacht", which describes the battle from a Cherusci point of view, on their 2015 album Ofnir.

- Barbarians, a German original series detailing the Roman Imperial campaign through Germania in 9 CE, premiered on Netflix in October 2020.[83]

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Main article: Hermannsdenkmal

The Hermannsdenkmal circa 1900

The legacy of the Germanic victory was resurrected with the recovery of the histories of Tacitus in the 15th century, when the figure of Arminius, now known as "Hermann" (a mistranslation of the name "Armin" which has often been incorrectly attributed to Martin Luther), became a nationalistic symbol of Pan-Germanism. From then, Teutoburg Forest has been seen as a pivotal clash that ended Roman expansion into northern Europe. This notion became especially prevalent in the 19th century, when it formed an integral part of the mythology of German nationalism.

In 1808 the German Heinrich von Kleist's play Die Hermannsschlacht aroused anti-Napoleonic sentiment, even though it could not be performed under occupation. In 1847, Josef Viktor von Scheffel wrote a lengthy song, "Als die Römer frech geworden" ("When the Romans got cheeky"), relating the tale of the battle with somewhat gloating humour. Copies of the text are found on many souvenirs available at the Detmold monument.

The battle had a profound effect on 19th century German nationalism along with the histories of Tacitus; the Germans, at that time still divided into many states, identified with the Germanic peoples as shared ancestors of one "German people" and came to associate the imperialistic Napoleonic French and Austro-Hungarian forces with the invading Romans, destined for defeat.

As a symbol of unified Romantic nationalism, the Hermannsdenkmal, a monument to Hermann surmounted by a statue, was erected in a forested area near Detmold, believed at that time to be the site of the battle. Paid for largely out of private funds, the monument remained unfinished for decades and was not completed until 1875, after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 unified the country. The completed monument was then a symbol of conservative German nationalism. The battle and the Hermannsdenkmal monument are commemorated by the similar Hermann Heights Monument in New Ulm, Minnesota, US, erected by the Sons of Hermanni, a support organisation for German immigrants to the United States. Hermann, Missouri, US, claims Hermann (Arminius) as its namesake and a third statue of Hermann was dedicated there in a ceremony on 24 September 2009, celebrating the 2,000th anniversary of Teutoburg Forest.

In Germany, where since the end of World War II there has been a strong aversion to nationalistic celebration of the past, such tones have disappeared from German textbooks.[26] Commemoration of the battle's 2,000th anniversary in 2009 was muted.[26] According to Der Spiegel, "The old nationalism has been replaced by an easy-going patriotism that mainly manifests itself at sporting events like the soccer World Cup."[26]

Да би разумјели ове догађаје ваља се вратити мало у прошлост.

Римљани су већ раније тежиште операције и експанзије пренијели на десну обалу Рајне која је једно вријеме била природна граница.

У успјешној кампањом 12-8.године п.н.е. коју је предводио Друз I потчинили су својој власти германска племена на том простору

Као залог вјерности Риму владар једног од најбројнијих германских племена Херуска, Сегимер дао је своје синове као таоце, уједно да у Риму буду одгојени и стекну образовање. Синови су упамћени по римским именима Арминије и Флавије.

Римљани јесу потчинили својој власти нека германска племена, међутим отпор других гермамских племена наставио се наредних година.

Посебмо је ојачало племе Маркомана предвођени амбициозним краљем Марободом, који су постали опасни ривал Риму.

Маробод је имао снажну и добро увјежбану армију, по Велеију Петеркулу (овдје, погл. 109);

Његова армија је бројала: 70.000 пјешака и 4.000 коњаника, у оперативном смислу способна војска, састављена од ратника ветерана прекаљених у бројним биткама претходних година када су покорили сва околна племена, војска са побједничким менталитетом, то су увијек опасни противници.109 The body of guards protecting the kingdom of Maroboduus, which by constant drill had been brought almost to the Roman standard of discipline, soon placed him in a position of power that was dreaded even by our empire. His policy toward Rome was to avoid provoking us by war, but at the same time to let us understand that, if he were provoked by us he had in reserve the power and the will to resist. The envoys whom he sent to the Caesars sometimes commended him to them as a suppliant and sometimes spoke as though they represented an equal. Races and individuals who revolted from us found in him a refuge, and in all respects, with but little concealment, he played the part of a rival. His army, which he had brought up to the number of seventy thousand foot and four thousand horse, he was steadily preparing, by exercising it in constant wars against his neighbours, for some greater task than that which he had in hand. He was also to be feared on this account, that, having Germany at the left and in front of his settlements, Pannonia on the right, and Noricum in the rear of them, he was dreaded by all as one who might at any moment descend upon all. 4 Nor did he permit Italy to be free from concern as regards his growing power, since the summits of the Alps which mark her boundary were not more than •two hundred miles distant from his boundary line. 5 Such was the man and such the region that Tiberius Caesar resolved to attack from opposite directions in the course of the coming year. Sentius Saturninus had instructions to lead his legions through the country of the Catti into Boiohaemum, for that is the name of the region occupied by Maroboduus, cutting a passage through the Hercynian forest which bounded the region, while from Carnuntum, the nearest point of Noricum in this direction, he himself undertook to lead against the Marcomanni the army which was serving in Illyricum.

Војска Маркомана је пролазила кроз темељиту војну обуку тако да се по квалитети и организацији нису били далеко од римског ратног строја.

Зато је Рим 6.године н.е. предузео војни поход против Маркомана са намјером да помјере границе царства са Дунава на Лабу.

Тиберије који је имао врховну команду је развио план напада великом војском из два правца. Један правац напада ће водити бивши конзул и врло способан заповједник Сентиус Сатурнин из смјера данашњег града Маинца у Њемачкој, који је повео 3 легије, 17., 18. и 19. легију (ПС; ове 3 легије су важне за ову тему), кроз област племена Кати (касније Бохемија) коју су Маркомани покорили ударио је са запада на Маробода.

Другу већу војску, најмање 8 легија, из правца Норика водио је лично Тиберије.

Римска војска бјеше велика 60-65.000 легионара, 10.000 коњаника те 10-20.000 помоћних снага, добро вођена од искусних стратега, бјеше пред великом побједом, но тада су примили вијест о избијању устанка у Илирику.

Тиберије је морао брзо реаговати, кампања и непријатељства су хитно прекинута, Маробод је рекао “охо, хо, ово добро испаде“, на брзину је склопљен мировни споразум, све Тиберијеве снаге које су пошле из правца Норика су повучене у Илирик, ту су се придружиле легије из Тракије и Македоније, и наредне 3 године на гушењу побуне у Илирику ангажовано је 15 легија (од 28 са колико је Рим располагао) и још толико помоћних снага, никад Рим није већу војску ангажовао на гушењу побуне и највећа римска војска од времена пунских ратова. Поменуте 3 легије (XVII, XVIII и XIX) на челу са Сатурнином су остале у Германији како би контролисали германска племена уз Рајну.

Сатурнин бива враћен у Рим а замјењује га Публије Квинтилије Вар који је преузео команду над овим легијама.