Srpski četnici na početku dvadesetog veka (2)

Neuspeli Ilindenski ustanak

Žestoka turska odmazda, spaljeno oko 150 sela, organizatori pobegli u Bugarsku

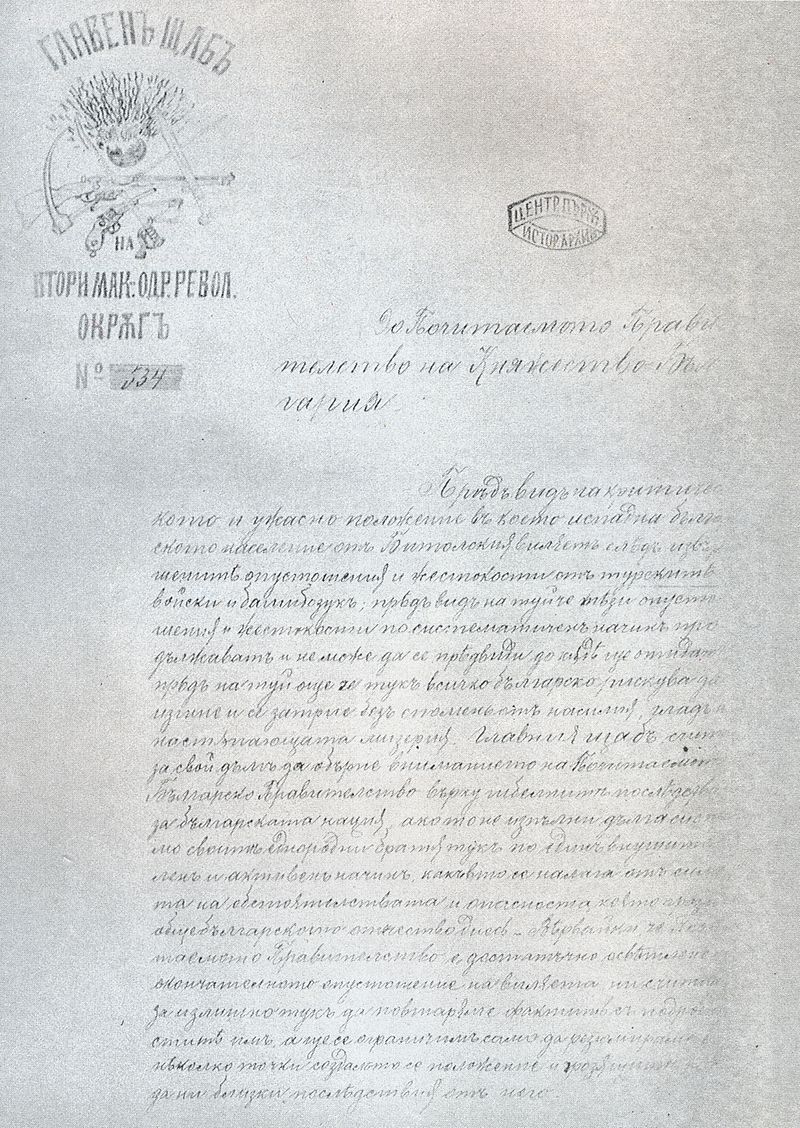

Neuspeli ilindenski ustanak, koji je u organizaciji VMORO otpočeo 2. avgusta 1903. u Bitoljskom vilajetu, okončan je posle deset dana žestokim turskim odmazdama. Vojska i bašibozuk (neregularne jedinice) spalili su oko 150 sela (blizu 40.000 ljudi ostalo je bez domova), veliki broj hrišćana je ubijen i oko 10.000 prinuđeno je da emigrira.

Organizatori ustanka Boris Sarafov, Damjan Grujev, Anastas Lozančev i Nikola Karev na vreme su pobegli u Bugarsku, ostvarivši svoj osnovni cilj, internacionalizaciju "makedonskog pitanja".

Carevi Austrougarske i Rusije, Frac Josif II i Nikola II, kao mandatori evropskih sila, sklopili su, 2. oktobra 1903. u štajerskom zamku Mircšteg, plan reformi za Makedoniju. Mircšteškim sporazumom bila je predviđena kontrola sprovođenja reformnog plana preko austrougarskog i ruskog civilnog agenta, reorganizacija žandarmerije pod komandom stranog generala i nadzorom njemu potčinjenih stranih oficira, učešće hrišćana u upravnoj i sudskoj vlasti, amnestija ustanika, obeštećenje postradalih, repatrijacija izbeglica, itd.

Nastanak komiteta

Porta je, krajem januara 1904. prihvatila reformni plan iz koga su bile izuzete samo oblasti sa znatnim ili pretežnim arbanaškim življem. Prema rasporedu reforma žandarmerije, austrougarski oficiri su dobili Kosovski vilajet, ruski Solunski, italijanski Bitoljski, dok je Dramski sandžak (okrug) pripao engleskim, a Sereski francuskim oficirima.

Do stvaranja Srpskog komiteta, kojim je Srbija stupila u četničku akciju, došlo je na inicijativu dr Milorada Gođevca, šefa lekara beogradske opštine. On je, vršeći po službenoj dužnosti sanitarnu kontrolu beogradskih aščinica, pekara i buregdžinica, čiji su vlasnici bili iz Stare Srbije i Makedonije, svojom blagonaklonošću i predusretljivošću, stakao veliki ugled kod ovih ljudi.

Tu se upoznao sa vojvodom Stojanom Donskim, pripadnikom VMORO, koji je u Beogradu provodio zimu. Donski ga je uputio u metode i statut VMORO. Gođevčeva zamisao bila je da, prema iskustvima bugarske, formira odgovarajuću srpsku organizaciju.

Za ovu ideju najpre je pridobio bankara Luku Ćelovića, a zatim advokata Vasu Jovanovića, sabrata iz masonske lože "Pobratim". Ubrzo im je prišao penzionisani ministar, vojni general Jovan Atanacković, u čijoj je kući u Krunskoj ulici, u leto 1903. osnovan Srpski komitet.

U okviru Komiteta formirane su tri sekcije: revolucionarna, propagandna i finansijska. Članovi Srpskog komiteta postali su: Jovan Atanacković, Milorad Gođevac, Luka Ćelović, akademici Ljubomir Kovačević, Ljubomir Jovanović i Ljubomir Stojanović, političari Živan Živanović, Ljubomir Davidović i Jaša Prodanović, major Petar Pešić, činovnik Ministarstva inostranih dela Milutin Stepanović, restorater Svetozar Stefanović i trgovac Dimitrije Ćirković.

Na istom sastanku izabrani su za članove Centralnog odbora Jovan Atanacković (predsednik), Milorad Gođevac, Ljubomir Davidović, Ljubomir Jovanović, Jaša Prodanović, Dimitrije Ćirković, Luka Ćelović, hotelijer Golub Janić, trgovac Nikola Spasić i Milutin Stepanović (blagajnik i sekretar). Takođe donet je i statut Komiteta pod nazivom: "Ustrojstvo (Ustav) Tajnog srbo-maćedonskog udruženja (organizacija)".

U zoru 30. avgusta položili su zakletvu članovi novoosnovanog Vranjskog odbora, koji će ubrzo postati Izvršni odbor četničke organizacije. Za predsednika je izabran kapetan Živojin Rafajlović, sekretara učitelj Mihailo Stevanović - Mile Cupara, blagajnika kafedžija Panta Jovanović, dok su članovi postali inspektor Monopola duvana Milan Graovac, šef železničke stanice Dragiša Lukić i apotekar Velimir Karić.

Kola sestara

Istoga dana, u beogradskoj dvorani "Kolarac", na inicijativu slikarke Nadežde Petrović, osnovano je humanitarno društvo za pomoć ilindanskim pogorelcima - Kolo srpskih sestara. Prikupljenih 60 napoleona odnele su u Makedoniju Nadežda Petrović i Mica Dobri i predale ih upravitelju porečkih škola Marku Ceriću, poznatom nacionalnom radniku.

Konačno, 30. avgust je obeležen i mitingom na Pozorišnom trgu u Beogradu pod parolom:"Sloboda svim neoslobođenim Srbima sa Srbijom zajedno ili smrt i samoj Srbiji".

Mitingu, koji je presudno uticao na stupanje Srbije u ilegalnu oružanu akciju, održanom pred oko 10.000 ljudi, prisustvovali su kao predstavnici političkih stranaka: radikal Aca Stanojević, samostalac Ljubomir Stojanović, naprednjak Živojin Perić i liberal Živan Živanović.

Govornici su bili: prota Aleksa Ilić, profesor Rista Odavić, Živan Živanović, velikoškolci Jevrem Simić i Jovan Đaja i Porečanin Naum Jamandijević, obučen u belu nošnju svoga kraja. Jamandijević, čiji je govor izazvao oduševljenje prisutnih, rekao je:

"Mnogo je godina proteklo kako Maćedonija čeka povratak Srbije. Nas su Arnauti i Bugari bili, a vi ste ćutali. Turci nas sada gone, sve se na nas okomilo. Duša je u podgrlac došla. Ginimo kao što Srbi ginu, kao potomci Kraljevića Marka! Vi nas ne smete ostaviti! Ako mi u Makedoniji izginemo i vi ćete!"

Ubrzo po formiranju Centralnog i Izvršnog odbora osnovan je Pododbor u Nišu, a kasnije i u nekim drugim mestima Srbije. Njihov zadatak bio je da propagiraju četničku akciju i prikupljaju pomoć u novcu i materijalu. Ove pododbore osnivali su najugledniji meštani. Na terenu, u Kumanovu, Skoplju i Bitolju, već su postojali odbori, nastali samoorganizovanjem tamošnjih Srba. Njima su veliku pomoć pružali konzulati u Bitolju i Skoplju.

Piše: Vladimir Ilić,

Glas javnosti